Posts Tagged Trey Songz

The Fate Of The 808

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Production, Remixing on August 3, 2010

The machine has been co-opted countless times to lend street cred to artist branding: early 90s UK techno act christened themselves 808 State; Kanye West dropped it in the title of his disc 808s & Heartbreak. And it’s regularly referred to by name in tracks like–wait for it–’808′ by Blaque. By now, the machine is more famous than some of the artists that use it. When Blaque sings ’cause I’ll be going boom like an 808,’ or Will.I.Am chants ‘we got the beat, that 808′ on the Black Eyed Peas’ ‘Boom Boom Pow’, we know they’re talking about the SUV-shaking kick of the world’s most celebrated drum machine, the Roland TR-808.

Legend has it that, in 1981, fledgling New York producer Arthur Baker travelled out to Jersey to buy a used 808. Roland had been manufacturing the unit for a couple of years, but like many new boxes, years can pass before someone stumbles upon a way to bring the art out of the technology. Baker brought the machine home and, reportedly, not knowing how to program it yet, he used a beat left in its memory by the previous owner as the basis of seminal rap track ‘Planet Rock’ by Afrika Bambaataa & Soulsonic Force, thus lifting the 808 from a potential fate of being a cheap novelty item stacked on pawn shop shelves for eternity. And that is how the disillusioned previous owner of that 808 turned out to be the nameless, faceless originator of that foundational ‘freestyle’ rap beat.

As the 80s progressed simple 808 beats began appearing on R&B jams by monster artists. After a short lull the machine had a strong resurgence in the early 90s, newly realized, in the stuttering double-time swing of ‘miami bass’ and ‘booty’ tracks. Post- millennium, its status as a classic has regularly been reinforced with new rap trends like Plies’ Southern post-booty beats and most recently in the sparse, ultra-high impact production sound of Kanye West and Drake.

Here are the basic, untweaked sounds of an 808.

The low, long tone of the kick drum is what most people recognize first. The clap, snare and cymbal sounds have come to feel like the sleek natural compliment to that low end, and the ‘cowbell’ sound, which bears little sonic resemblance to a cowbell at all, is really some kind of synthesized fifth chord.

Some 808 beats over the last 3 decades: the original freestyle beat of ‘Planet Rock’ by Afrika Bambaataa and Soulsonic Force (1982); straight ahead R&B jams ‘Sexual Healing’ by Marvin Gaye (1982) and ‘Who’s Zoomin’ Who’ by Aretha Franklin (1985); the syncopated miami bass beat on Inoj’s cover of Cyndi Lauper’s ‘Time After Time’ (1998) which incorporates a snare sample from another machine; Southern rapper Plies’ ‘Plenty Money’ (2008); the sparse 808 kick intro ‘Heartless’ by Kanye West (2008); ‘Successful’ by Drake ft. Trey Songz (2009).

In the early 80s Roland made a complete line of something-oh-something units. The 303 was a bass sequencer, initially relegated to the accompaniment of one-man polka bands and the like until it found a perfect home within the rhythms of late-80s acid house and mid-90s techno.

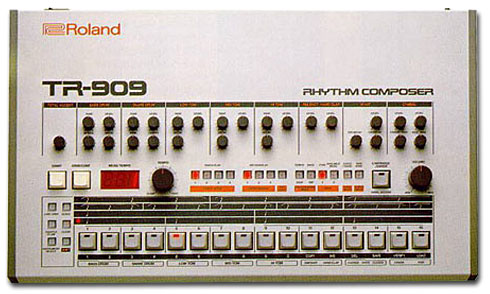

The 909 drum machine also sat, semi-used, until disco re-emerged…re-branded as ‘house’ in the late 80s: the 909 is to House as the 808 is to R&B and Hip Hop. The machine’s solid, pointed kick drum, crisp high hats and full-bodied clap, used together, ushered in the meditative swing of house music. In particular, rolling the 909’s snare in a multitude of syncopated patterns became the thing to do.

The 909 in action: pre-house snare rolls and echoey clap patterns on ‘Pump Up The Volume’ by M.A.R.R.S. (1987); syncopated snare on ‘E.S.P.’ by Deee-Lite (1990); Shep Pettibone’s snare-happy house mixes of ‘Escapade’ by Janet Jackson, ‘Express Yourself’ and ‘Vogue’ by Madonna (1989-90); MK’s 909-heavy remixes of ‘Movin’ On Up’ by M People, ‘Can You Forgive Her’ by the Pet Shop Boys and ‘Heart Of Glass’ by Blondie (1993-95); and a 909-only beat on the Musk Men bootleg of ‘I Never Thought I’d See The Day’ by Sade (1995).

There are a few other early drum machines worth noting for the impact they had on music as we know it.

Roger Linn created the Linn LM-1 in 1980, and it quickly became the go-to machine for pop production in the U.S. and U.K.

The LinnDrum and Linn 9000 models followed, adding a few more sounds to the initial palette.

Countless instantly recognizable beats were programmed on these machines including ‘The Look Of Love’ by ABC, ‘Don’t You Want Me’ by the Human League, ‘Love Is A Battlefield’ by Pat Benatar, ‘Shock The Monkey’ by Peter Gabriel, ‘Dress You Up’ by Madonna, ‘Wanna Be Starting Something’ by Michael Jackson, ‘Mama’ by Genesis and ‘Everything She Wants’ by Wham.

A friend used to joke that Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis must have had a climate-controlled room with a sleek black box the size of a tank to produce sounds as big and clunky as they used on Janet Jackson’s ‘Control’ and ‘Rhythm Nation’ albums. Evidently, however, the production team often used Linn machines drenched in gated reverb for Jackson’s signature sound.

Prince crafted virtually everything he produced in the 80s with these machines as well as two others, defining a funk sound we all know.

The raw sounds on Sequential Circuits’ Drumtraks sounded like this:

Oberheim’s OB-DX sounded like this:

With a little manipulation (re-pitching the sounds and adding various effects to them) he was able to create a fresh basis for each new song while defining his production sound. In particular, he seemed to use the Drumtraks clap a different way on virtually every track.

Some samples of Prince’s production from ‘Nasty Girl’ by Vanity 6, through a range of his solo work over the decade including ‘Let’s Pretend We’re Married,’ ‘Little Red Corvette,’ ‘Let’s Go Crazy,’ When Doves Cry,’ ‘The Beautiful Ones,’ ‘Raspberry Beret’ and ‘Kiss’:

No tour through notable 80s drum machines would be complete without mentioning Simmons drums. These were actual physical drum kits produced in varying incarnations between 1980 and 1990 with hexagonal electronic pads that triggered a synthesizer box.

Some individual sounds.

The instantly recognizable white noise fakeness shows up sporadically on all kinds of prog rock, new wave and funk. Some examples are the intro to ‘Somebody Told Me’ by the Eurythmics, the whole drum groove of ‘She Blinded Me With Science’ by Thomas Dolby, the accents in the break of ‘Mr. Roboto’ by Styx, and the snare on ‘Word Up’ by Cameo.

This Guy’s Crazy

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Writing on January 4, 2010

In general I’m far more interested in hearing a singer-songwriter deliver their own lyric than hearing a performer sing something that was penned for them by an assembly line writer. By definition, I think a singer who chronicles their own thoughts and feelings can deliver authentic human experience more directly than one who acts out lines crafted by another person. So I cherish the work of auteurs like Stevie Wonder and Joni Mitchell, and I’ll take Alanis Morissette over Britney Spears and Mary J. Blige over Whitney Houston.

I can certainly leave a tradesperson like Diane Warren, who for many years was LA’s go-to writer for romantic schlock like Toni Braxton’s ‘Unbreak My Heart’ and Celine Dion’s ‘Because You Loved Me’. Warren claims never to have been in love, and she hates dating. In a way, her inexperience with love does show in the almost camp, overshot grandiosity of her lyrics. And while overshot sentiment sells because it gets its point across quickly and clearly, I just have a fundamental issue with pinning my own romantic yearnings to somebody’s calculated product.

But there are exceptions to my ban. One is the Motown assembly line of the 60s, in which Holland-Dozier-Holland wrote the most significant portion of the material for an entire stable of artists in Detroit. My theory there is that the momentum of the label’s fresh, exciting sound and the writers’ melodic gifts attracted every aspiring singer in the city…and then the universality of the lyrics allowed the singers to throw themselves into performances convincingly, as though the songs were confessionals from their own lives…similar to an artist choosing to record a cover version of someone else’s song because it has tremendous personal significance for them.

Another exception is New York’s Brill Building, which fostered a competitive atmosphere for songwriters, peaking in output in the late 50s and early 60s with Burt Bacharach, Neil Diamond, Carole King, Neil Sedaka and Phil Spector all hanging around, pushing each other to be greater songsmiths. Again: an almost magical kind of momentum seems to have been present.

Those I would call auteurs appear to discover the chorus of a song organically from a personal feeling or event they’re describing. In contrast, assembly-line writing often involves first searching for one original, evocative central concept (ie ‘You Make Me Feel Like A Natural Woman’ came out of the Brill Building for Aretha Franklin) that will serve as the chorus, and then fashioning the rest of the song outward from that…creating verses and bridges that will set up and support the story, always bringing us back to the point the chorus makes. Slightly cheaper than working from an original central concept, an unused pop culture catch-phrase will suffice as the chorus (Motown’s writers gave ‘You Beat Me To The Punch’ to Mary Wells). Today much top 40 rap is based around nabbing the most up-to-the-minute catch-phrases and creating a cool/dirty/funny track around that (see ‘Superman That Hoe‘ a/k/a ‘Crank That’ by Soulja Boy).

A few weeks ago Island/Def Jam artist Jenna Andrews played me a rough cut of her upcoming debut album. A gorgeous production featuring her instantly recognizable voice upfront, much of it was penned by the industry’s fastest-climbing new writer Claude Kelly. And I need to tell you…this guy’s crazy. Jenna described his pen-and-paperless process to me: he toplines (writes lyrics and melodies over instrumental tracks) by getting into the vocal booth, turning down the lights, balling up on the floor and having the engineer play the track on repeat for a while. He locks in to who he’s writing for and finds the sentiment. Then he gets up and writes at the mic, no doubt influenced by the freestyle process of many rappers…but he also mimics the voice of the person he’s writing for. He goes back and forth within the song as necessary, changing and filling in lines, taking about two hours to put down an entire song complete with background vocals.

Claude’s still in his 20s and he’s already written hits in several styles, including ‘Circus’ for Britney Spears, ‘Party In The U.S.A.’ for Miley Cyrus and Adam Lambert’s ‘For Your Entertainment.’ He’s written extensively for Akon and Toni Braxton, and for Whitney Houston’s comeback album. To understand the way he embodies the singer he’s writing for, check out the excellent ‘I Hate Love,’ a demo he recorded for Toni Braxton. The song’s unique central concept is the idea that someone could come to hate being in love because each day spent away from your lover is exceedingly painful. This oddly dark sentiment is somehow appropriate for her persona and his delivery is full of Braxtonisms. A quick search of his name on YouTube reveals an array of leaked demos of unreleased songs for a range of artists…judging by the sound of his delivery, some of them would seem to be for Akon, Whitney Houston, and Trey Songz.

We have modern-day net leakage to thank for this type of insight into a fascinating writing process. I hate to throw the phrase ‘bonafide genius’ around, but let’s say Claude Kelly is a talent to watch. It would be even more interesting to hear a Claude Kelly solo record, giving him the opportunity to step into the role of auteur…and to sing as himself.