Posts Tagged Mirwais

Breakin’ Dishes: Capturing Sound Not So Perfectly

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Production on June 7, 2009

When somebody drops a glass or breaks a plate in the apartment next door, you know it’s happening for real–and not in a surround-sound movie they’re watching–because what we can capture on disc is still slightly lower quality than real life sound.

Since the first recordings made on cylinders in the late 1800s we’ve always pressed forward, unquestioningly, in our efforts to close the gap between ‘live and memorex’. Technologists, engineers and audiophiles have fought tirelessly to further extend the frequency range, dynamics and resolution of recordings. In the late 80s the jump to digital recording brought us infinitely closer to being able to reproduce sound without colouration of any kind, and science continues to improve upon the resolution of digital with the goal, I suppose, of having there be no discernable difference between real and reproduced sound.

This has been amazing for action movies. In some instances crisp, clear recordings with deep bass, pristine treble, wide spatial staging and infinite dynamic range should be the goal. But there is also a powerful group of mostly old-school music producers–the David Foster types, the Nashville types–that in my opinion have chosen to use the widescreen ‘colourless’ nature of digital to strip mainstream recordings of much of their character.

Looking back on pop culture over the last hundred years, some of what we hold dearest is that which we can’t quite ‘touch’…that which is partially obscured because it wasn’t captured realistically.

When we watch a black and white movie from the 1930s, a technicolor movie from the 1950s, or even a film shot on washed out Kodakchrome/Eastman stock from the 1970s, we’re losing ourselves in a world that is not quite our own…it’s a romanticized version of life brought to us in part due to a lack of honest colour information.

Similarly, when we listen to classic Motown, with its boxy sounding drums, distorted tambourines and general sonic blurriness, we’re transported to that sweaty basement in Detroit where players and singers delivered magic. And it’s not just nostalgic in retrospect. I maintain that it was already full of nostalgia when it first hit the radio precisely because it didn’t sound like real life: the very character of the sound stoked our collective imagination as to where this musical spirit was coming from.

If music is a window into other peoples’ real and imaginary worlds, why is there so often a de facto assumption that we even want it to sound true-to-life? And, once it’s possible to record sound at real-life resolutions, does that mean we’ll cease to experience decade-specific nostalgia as, moving forward, sound is always perfectly colourless?

I always tend to appreciate the planned or accidental limitation of sound quality, like a good pair of distressed jeans. I don’t feel that the most expensive microphone, the biggest mixing desk, or the greatest clarity and sonic detail should always be the goal. Capturing a moving performance should be first, and if a lower end microphone is all that was around when it happened, I don’t believe the artist should re-perform it on a $17k Neumann tube mic. In fact maybe a Fisher Price microphone should be plugged in now and again to see what will happen.

Some examples of intentionally and unintentionally ‘distressed’ recordings through the ages:

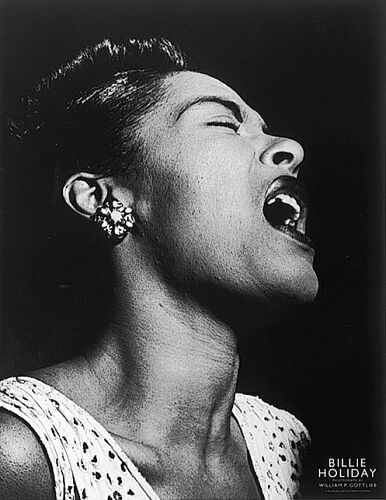

1. Billie Holiday’s 1935 recording ‘It’s Too Hot For Words’ was of course cut on a shellac disc using relatively primitive equipment. The dated style of the recording–the distortion and lack of bass and treble information–renders her forever untouchable, a tragic legend.

2. On ‘Strangers,’ the third track on Portishead’s 1994 groundbreaking debut disc ‘Dummy’, after a full frequency sonic barrage of an intro we plunge unexpectedly into what appears to be an improvised demo jam made on a handheld cassette recorder. Muted, distorted and noisy, Adrian Utley’s soulful jazz electric supports some of Beth Gibbons’ most shimmering vocal moments. This section of the song may in fact have been laboured over on high end recording equipment and then played back through a distorted guitar amp to achieve this effect…we may never know. By verse 2 we’re back in 1994 standards of high definition audio.

3. Throughout the 1990s layering vinyl surface noise over highly produced rap, R&B and pop was a common move to get back some of the nostalgia that seemed to be lacking on pristine digital recordings. 1996’s ‘No Love’ by Erykah Badu demonstrates the tactile feel of vinyl, as well as an intro section where the bass and treble are also filtered out of the music to make it sound lo-fi. When the track kicks in (and the filters are removed) note that the quality of the instruments is uncompromised by the vinyl pops we hear over top. This gave 1990s recordings a different feel than old recordings on actual damaged vinyl, because each click or pop on a record would actually distort the sound quality of the musical elements as it happened.

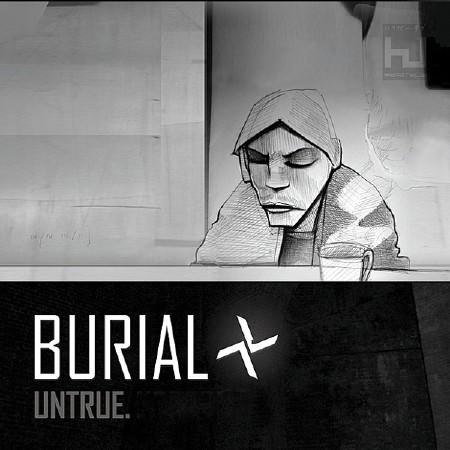

4. UK dubstep producer Burial puts down a bed of heavy, stuttering beats. On that he places a wax paper layer of lush, filmic ambient pads. Next, he sprinkles obscure mix-and-match R&B acapellas, filtering out the treble to create lyrical ambiguity. Finally he wraps the whole thing in a layer of sonic gauze using an expanded palette of crackle, ranging from standard vinyl crackle and tape hiss to rustling sounds and recordings of fire. The result, heard here on a drumless segue after ‘Shell Of Light’ on his 2008 album ‘Untrue’, is something like witnessing a merciful event through a frosted window.

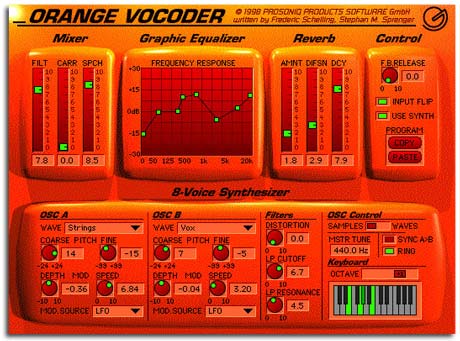

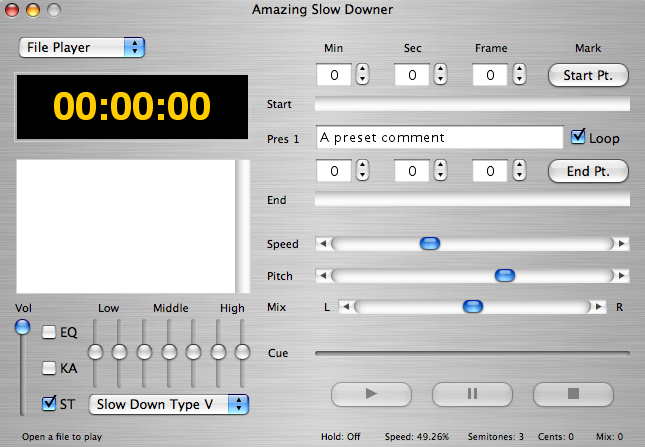

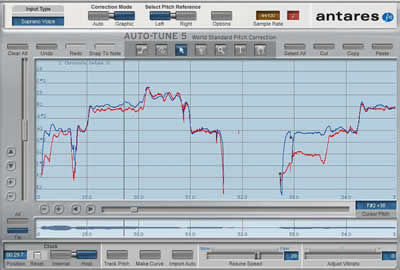

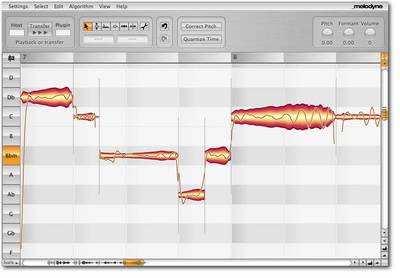

These are all analog methods of bringing character to recordings: the limitations of vinyl, tape and guitar amps. But in the early part of this century we’ve seen some indication that producers will continue to time-stamp recordings by beginning to find useable limitations within the digital realm. For example, the glassy digitized sound of low quality mp3s has inspired some producers (most notably Mirwais, who produced Madonna’s ‘Music’ and ‘American Life’ albums…and of course Daft Punk) to apply similar lo-fi digital effects to vocals and music loops.

This type of experimentation gives me hope, in the digital age, that we won’t be listening to the silky smooth sound of David Foster muzak for the rest of eternity.