Posts Tagged Marvin Gaye

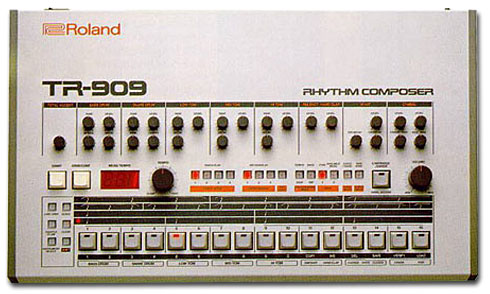

The Fate Of The 808

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Production, Remixing on August 3, 2010

The machine has been co-opted countless times to lend street cred to artist branding: early 90s UK techno act christened themselves 808 State; Kanye West dropped it in the title of his disc 808s & Heartbreak. And it’s regularly referred to by name in tracks like–wait for it–’808′ by Blaque. By now, the machine is more famous than some of the artists that use it. When Blaque sings ’cause I’ll be going boom like an 808,’ or Will.I.Am chants ‘we got the beat, that 808′ on the Black Eyed Peas’ ‘Boom Boom Pow’, we know they’re talking about the SUV-shaking kick of the world’s most celebrated drum machine, the Roland TR-808.

Legend has it that, in 1981, fledgling New York producer Arthur Baker travelled out to Jersey to buy a used 808. Roland had been manufacturing the unit for a couple of years, but like many new boxes, years can pass before someone stumbles upon a way to bring the art out of the technology. Baker brought the machine home and, reportedly, not knowing how to program it yet, he used a beat left in its memory by the previous owner as the basis of seminal rap track ‘Planet Rock’ by Afrika Bambaataa & Soulsonic Force, thus lifting the 808 from a potential fate of being a cheap novelty item stacked on pawn shop shelves for eternity. And that is how the disillusioned previous owner of that 808 turned out to be the nameless, faceless originator of that foundational ‘freestyle’ rap beat.

As the 80s progressed simple 808 beats began appearing on R&B jams by monster artists. After a short lull the machine had a strong resurgence in the early 90s, newly realized, in the stuttering double-time swing of ‘miami bass’ and ‘booty’ tracks. Post- millennium, its status as a classic has regularly been reinforced with new rap trends like Plies’ Southern post-booty beats and most recently in the sparse, ultra-high impact production sound of Kanye West and Drake.

Here are the basic, untweaked sounds of an 808.

The low, long tone of the kick drum is what most people recognize first. The clap, snare and cymbal sounds have come to feel like the sleek natural compliment to that low end, and the ‘cowbell’ sound, which bears little sonic resemblance to a cowbell at all, is really some kind of synthesized fifth chord.

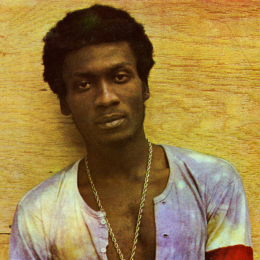

Some 808 beats over the last 3 decades: the original freestyle beat of ‘Planet Rock’ by Afrika Bambaataa and Soulsonic Force (1982); straight ahead R&B jams ‘Sexual Healing’ by Marvin Gaye (1982) and ‘Who’s Zoomin’ Who’ by Aretha Franklin (1985); the syncopated miami bass beat on Inoj’s cover of Cyndi Lauper’s ‘Time After Time’ (1998) which incorporates a snare sample from another machine; Southern rapper Plies’ ‘Plenty Money’ (2008); the sparse 808 kick intro ‘Heartless’ by Kanye West (2008); ‘Successful’ by Drake ft. Trey Songz (2009).

In the early 80s Roland made a complete line of something-oh-something units. The 303 was a bass sequencer, initially relegated to the accompaniment of one-man polka bands and the like until it found a perfect home within the rhythms of late-80s acid house and mid-90s techno.

The 909 drum machine also sat, semi-used, until disco re-emerged…re-branded as ‘house’ in the late 80s: the 909 is to House as the 808 is to R&B and Hip Hop. The machine’s solid, pointed kick drum, crisp high hats and full-bodied clap, used together, ushered in the meditative swing of house music. In particular, rolling the 909’s snare in a multitude of syncopated patterns became the thing to do.

The 909 in action: pre-house snare rolls and echoey clap patterns on ‘Pump Up The Volume’ by M.A.R.R.S. (1987); syncopated snare on ‘E.S.P.’ by Deee-Lite (1990); Shep Pettibone’s snare-happy house mixes of ‘Escapade’ by Janet Jackson, ‘Express Yourself’ and ‘Vogue’ by Madonna (1989-90); MK’s 909-heavy remixes of ‘Movin’ On Up’ by M People, ‘Can You Forgive Her’ by the Pet Shop Boys and ‘Heart Of Glass’ by Blondie (1993-95); and a 909-only beat on the Musk Men bootleg of ‘I Never Thought I’d See The Day’ by Sade (1995).

There are a few other early drum machines worth noting for the impact they had on music as we know it.

Roger Linn created the Linn LM-1 in 1980, and it quickly became the go-to machine for pop production in the U.S. and U.K.

The LinnDrum and Linn 9000 models followed, adding a few more sounds to the initial palette.

Countless instantly recognizable beats were programmed on these machines including ‘The Look Of Love’ by ABC, ‘Don’t You Want Me’ by the Human League, ‘Love Is A Battlefield’ by Pat Benatar, ‘Shock The Monkey’ by Peter Gabriel, ‘Dress You Up’ by Madonna, ‘Wanna Be Starting Something’ by Michael Jackson, ‘Mama’ by Genesis and ‘Everything She Wants’ by Wham.

A friend used to joke that Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis must have had a climate-controlled room with a sleek black box the size of a tank to produce sounds as big and clunky as they used on Janet Jackson’s ‘Control’ and ‘Rhythm Nation’ albums. Evidently, however, the production team often used Linn machines drenched in gated reverb for Jackson’s signature sound.

Prince crafted virtually everything he produced in the 80s with these machines as well as two others, defining a funk sound we all know.

The raw sounds on Sequential Circuits’ Drumtraks sounded like this:

Oberheim’s OB-DX sounded like this:

With a little manipulation (re-pitching the sounds and adding various effects to them) he was able to create a fresh basis for each new song while defining his production sound. In particular, he seemed to use the Drumtraks clap a different way on virtually every track.

Some samples of Prince’s production from ‘Nasty Girl’ by Vanity 6, through a range of his solo work over the decade including ‘Let’s Pretend We’re Married,’ ‘Little Red Corvette,’ ‘Let’s Go Crazy,’ When Doves Cry,’ ‘The Beautiful Ones,’ ‘Raspberry Beret’ and ‘Kiss’:

No tour through notable 80s drum machines would be complete without mentioning Simmons drums. These were actual physical drum kits produced in varying incarnations between 1980 and 1990 with hexagonal electronic pads that triggered a synthesizer box.

Some individual sounds.

The instantly recognizable white noise fakeness shows up sporadically on all kinds of prog rock, new wave and funk. Some examples are the intro to ‘Somebody Told Me’ by the Eurythmics, the whole drum groove of ‘She Blinded Me With Science’ by Thomas Dolby, the accents in the break of ‘Mr. Roboto’ by Styx, and the snare on ‘Word Up’ by Cameo.

Song Structure 101

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Writing on June 14, 2009

Legend has it that Jane’s Addiction frontman Perry Farrell came up with ‘Been Caught Stealing’ specifically to prove he was capable of–though not particularly interested in–writing radio hits. Of course after the song spent four weeks at #1 and the band made the jump from college dorm buzz to a household name, Farrell had the resources to create Lollapalooza and retire back to writing whatever he felt like writing.

Formulaic writing gets a bad rap. Nobody wants to feel that the music they love was written in a calculated way, but I think it’s important to draw a distinction between upholding the tradition of the 3-minute pop song and completely reverse-engineering music based on market studies. The fact is, for better or worse, every one of us has been programmed to understand a couple of basic song structures.

The main one: Verse–Prechorus–Chorus–Verse–Prechorus–Chorus–Bridge–Chorus

Sometimes there’s a short intro. We expect the first verse to spell out what the song is going to be about. The prechorus that follows builds tension toward an anticipated payoff. The chorus is the catchy main idea that we’ve been waiting for–the repeated part that everyone can sing along to–and it usually contains the song title. (In olden times it was known as the ‘refrain’, and it’s more and more often referred to as the ‘hook’ in the age of hip hop.)

In the second verse the story continues to be told. Expect a new idea or a new perspective to be introduced, just when it might start getting boring. Lyrics are almost never repeated in verses. The prechorus that follows may contain the same words as the first, but it may be shortened to get to the second chorus faster. Next, three quarters of the way through the song, a bridge (or ‘b-section’) breaks the melodic pattern…it’s somewhere else to go for a moment. Sometimes solos are used in place of, or in addition to, bridges. Finally, we’re taken home with the biggest chorus yet at the end.

Occasionally you’ll get a song with no prechoruses, or one with an outro or ‘tag’ at the end. But this basic structure applies to virtually every song you’ve ever heard. Even long club mixes are the same: there’s just a longer intro, a longer bridge in the form of a drum break or build, and a longer outro.

Many new writers are unaware of this structure, or they will intentionally start writing without studying it with the belief that this will allow them to express themselves in a pure way, unfettered by convention. However it’s basically inevitable that when they do hit on a structure that feels right, it will be because they’ve kept moving parts around until they have something that follows the structure described above.

So it’s just faster to accept that this song arc is part of a language we’ve all learned subconsciously. It’s a tradition. There is still plenty of room within that tradition to be an individual. In many ways we should be thankful that the structure pins down a couple of constants for us. What sets writers apart is the substance they fill this pre-determined form with. And the more experienced writers will naturally begin to manipulate the structure in ways that make sense to all of us as listeners.

The other song structure worth mentioning is an older form that has its roots in gospel hymns: Chorus–Bridge–Chorus–Bridge–Chorus. Jimmy Cliff made use of its spiritual feel in his classic ‘Many Rivers To Cross’:

Each chorus begins with the lyric ‘Many rivers to cross,’ and from there he identifies another aspect of his tribulations: ‘…and it’s only my will that keeps me alive. I’ve been licked, washed up for years, and I merely survive because of my pride.’ The bridge section, which appears twice to provide a respite from the chorus, addresses his loneliness: ‘But loneliness won’t leave me alone. It’s such a drag to be on your own. My woman left and she didn’t say why. Well I guess I have to cry.’

One of the few songs in the history of pop music that defies convention is Marvin Gaye’s classic ‘Let’s Get It On’. The song does follow Chorus-Bridge-Chorus-Bridge-Chorus form, but the melody is ‘through-written,’ meaning each section takes a new melodic route, with very little repetition. It’s extremely difficult to write something that stays hooky throughout without ever repeating the melody…but if you think you know as much as Marvin Gaye knew about writing when he came up with the seemingly effortless ‘Let’s Get It On’, I encourage you to try it!