Posts Tagged Bjork

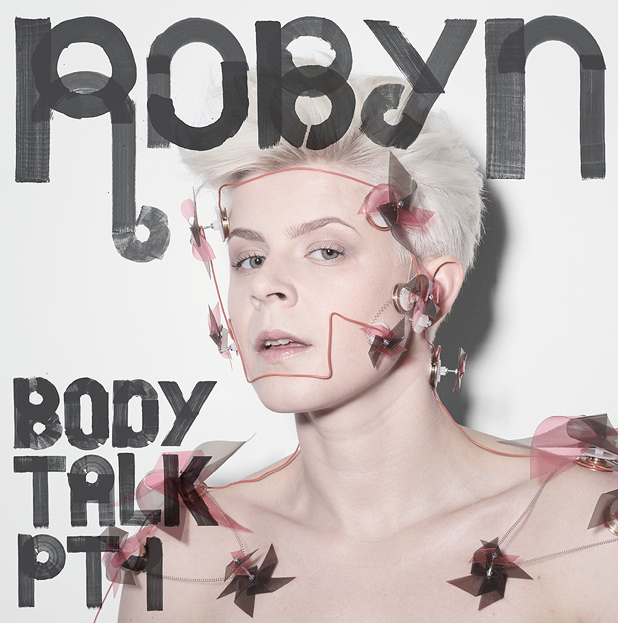

Pop Smarts: Robyn

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Labels, Production, Writing on November 4, 2010

In 1997, RCA Sweden and legendary writer-producer Max Martin unleashed cute 18-year old popster Robyn on the world, sending flares up international charts with the R&B-tinged ‘(Do You Know) What It Takes’ and ‘Show Me Love’. The rest of the world was left to wonder once again how—from Abba to Roxette and The Cardigans—many a Swede has been able to tap in effortlessly to the North American pop sensibility. Further, she was a nordic girl with a measure of genuine soul in her voice. After a few more minor hits in Europe, Robyn disappeared from the world stage as quickly as she had arrived.

Fast forward a decade.

Word of mouth began rippling through the English-speaking world: undefeated by her major-label crash-and-burn, she’d quietly and intelligently risen from the flames. Taking the reigns both creatively and businesswise, she’d honed her songwriting craft with some hot producers and tested a new electro-pop direction locally with singles like ‘Dream On’. After necessary alterations, a deftly conceived full-length album—titled, simply, Robyn—followed on her newly christened Konichiwa Records. (The album also kicked off with the braggadocio rap ‘Konichiwa, Bitches’ — it’s Japanese slang for ‘Good Day’.)

A further revised version of the album arrived internationally and was supported with exhaustive touring. In concert she gives 110%, with heaps of cover songs along with her extensive canon of self-penned work. Her choice of covers shows a wide appreciation of other artists’ work: ‘Buffalo Stance’ by Neneh Cherry, ‘Try Sleeping With A Broken Heart’ by Alicia Keys and ‘Hyperballad’ by Bjork. Why all the YouTube links in this post? Because each one is worth it.

What’s special here is not that she’s come with great material, or that she put in the grunt work to rebuild the value of her brand from the ground up. It’s that she has the rare gift of self-awareness as an artist; the intelligence with which she’s packaged and marketed herself.

This year was the best example of it yet. After a couple years of radio silence, late 2009’s stunning collaboration with Röyksopp, ‘The Girl And The Robot’, primed us for a well conceived three-part ambush in 2010. Rather than releasing an album, she presented three shorter EPs. Distilled, the contents of Body Talk, Parts 1-3 would make a solid longplay album. But in an era when digitally downloaded music makes the number of songs on a release irrelevant, by conceiving a flexible new model like this she’s found a way to keep the excitement going all year long. Installments arrived in June and September. The final disc is slated for November 22.

Musically, the Robyn formula is smart. By giving us 1 part emotionally-level dance fun (‘Handle Me’, ‘Dancehall Queen’, ‘We Dance To The Beat’) and 1 part pseudo-gangsta attitude (‘Curriculum Vitae’, ‘Don’t Fucking Tell Me What To Do’, ‘Fembot’) upfront, we’re ready to go the distance with her as her heart bleeds through the remaining third of the material. And this is the material that really sticks: ‘With Every Heartbeat‘, ‘Be Mine‘, ‘Dancing On My Own’, ‘Hang With Me’, ‘Indestructible’.

Cleverly, the first two EPs also contained acoustic ‘preview’ versions of the lead-off single planned for the next EP, guaranteeing a boost of familiarity when the single versions of ‘Hang With Me’ and ‘Indestructible’ arrived with a Giorgio Moroder-esque thud.

What’s also striking is that Robyn, the artist and the businesslady, seems to have captured a demographic few else realized was there for the taking: the 30-something ex-raver that still craves rap and club music but wants something personal, melodic…clever.

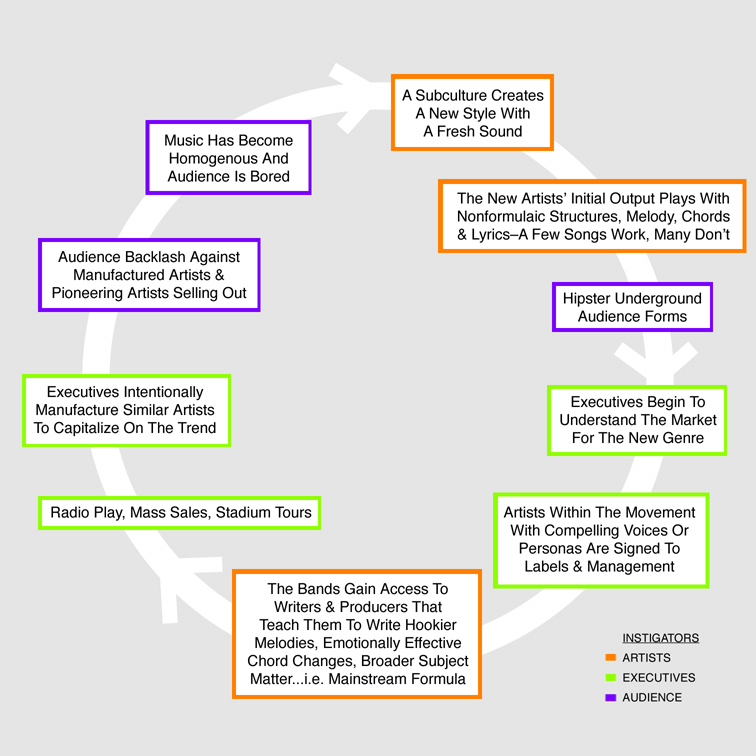

The Creative-Commercial Cycle: How Pop Eats Itself

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Labels, Management, Production, Radio, Writing on August 19, 2010

If it’s agreed that the following creative-commercial cycle occurs continuously in popular music…

…then there are a couple of things I find interesting. Namely, the process by which naturally compelling artists learn to create music with mass appeal, and the fact that this cycle seems to be speeding up as the executives get quicker at identifying and exploiting new trends.

For an example of the cycle, we can look at U2’s output. In the early 80s they had underground ‘alternative rock’ cool factor. The songs on their first two albums Boy and October were somewhat freeform. Melodies were cockeyed and noncommittal, lyrics never too direct. Bono’s voice and Edge’s guitar sound, together, supplied compelling personality. Steve Lillywhite’s production captured the band’s raw electricity without stylizing it.

War and The Unforgettable Fire followed, with ‘Sunday Bloody Sunday,’ ‘New Year’s Day’ and ‘Pride (In The Name Of Love)’ showing the first signs of a desire to write for radio. However, an inspired change in personnel brought a new depth to the sound of that fourth album: ambient visionary Brian Eno and roots musician Daniel Lanois were brought in to produce.

Not surprisingly, the subsequent writing on The Joshua Tree was significantly distilled. The straight-ahead stock chord changes and emotive melody of ‘With Or Without You’ as well as the clear, sweeping subject matter of ‘I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For’ and ‘Where The Streets Have No Name’ brought a mainstream audience to them as if by magnetic pull. If Eno and Lanois hadn’t purposely educated the band about mainstream pop writing, some form of growth-through-osmosis had happened as they opened up their creative circle.

Here’s a wordy section from ‘Drowning Man’ on War, followed by the confidence of the continuously building ‘With Or Without You’.

Since the watershed success of that album and the Rattle & Hum stadium tour–amid their core audience’s protests that the band had sold out–U2 has ridden out the last 20 years in various states of expectation-busting experimentation (Zooropa, The Passengers’ Original Soundtracks project) and pop duty fulfillment (All That You Can’t Leave Behind).

Bjork–who, incidentally, at first used her voice much like Bono had in the early 80s–first helmed Icelandic band Kukl, followed by The Sugarcubes. Her childlike voice and persona showed commercial promise amidst the disarray of the bands’ post-punk art-rock.

Teaming up with respected electronic producer Nellee Hooper, she emerged as a solo artist in 1993 with Debut, securing her place in pop history. The follow-up album was Post. ‘It’s Oh So Quiet,’ the big band single America loved to hate, was as straightforward as she would ever get before making her way back into ever-deeper experimental waters.

Compare the atonal rant from ‘Copy Thy Neighbour’ by Kukl with the soaring melody on the chorus of ‘Hyperballad’.

10,000 Maniacs is an interesting case that I made an effort to crack recently. I always had a like-hate relationship (as opposed to love-hate) with their In My Tribe, Blind Man’s Zoo and Our Time In Eden albums because I never quite understood how a band could sabotage moments of melodic virtuosity with such poorly considered arrangements. Or how such a compelling voice–meaning Natalie Merchant’s vocal instrument as well as the interesting angles she took on the songs’ subject matter–could be ruined by an equal helping of preachy condescension. As well, even after a string of five pop singles (‘Like The Weather,’ ‘What’s The Matter Here,’ ‘Trouble Me,’ ‘These Are Days’ and ‘Candy Everybody Wants,’) the band seemed to retain ‘alternative’ cred. Surely it couldn’t just have been based on their name.

A listen through their early recordings, reissued later on Hope Chest and The Wishing Chair, explained much. Like early U2 and Kukl, these songs are meandering stabs at writing, with hookless melodies, wordy, unclear lyrics and unremarkable chord changes. Also like Bono and Bjork, Merchant’s singular personality came through in her voice and the way she used it. 10,000 Maniacs guitarist Rob Buck, too, had an original style. Perhaps not as iconoclastic as Edge’s, but enough to show promise to a record company like Elektra. The band’s ‘alternative’ roots show in these recordings: in addition to the beginnings of their brand of quirky rock, we’re taken through painful world music experiments in Soca, Zouk and Dub Reggae.

‘Death Of Manolete’ from Hope Chest demonstrates the freedom of their wide-open creativity while the exquisite ‘Dust Bowl’ from Blind Man’s Zoo shows us the focus that took hold by the band’s second album with major label producer Peter Asher.

And so we have the artists, feeling around for something new to chew on, and the executives, racing to learn how to capitalize on a movement, a sound, an idea, a persona. They can’t exist without each other, so I don’t mean to imply that executives are the Cruella DeVilles of the world. But the crops need time to grow before the combine comes along to harvest. And in the age of the internet, traces of new artistic energy are identified and absorbed into the machine with breakneck acceleration.

One such ‘absorption cycle’ that makes me shudder is what occurred somewhere between 1995 and 2008, when Jill Sobule and Katy Perry each released a song called ‘I Kissed A Girl.’ Sobule’s song felt like the honest confession of a woman testing the fluidity of her sexuality. Perry’s felt like a market-researched ‘girls gone wild’ capitalization on straight mens’ fascination with girl-on-girl action. The sincere feminist perspective of artists like Sobule through the early 90s was officially absorbed into the machine when Simon Fuller auditioned British Barbie dolls for the Spice Girls. What was their mantra? ‘Girl Power’? Fast forward a decade, and it’s as though the feminist consciousness of the early 90s never existed. Lillith Fair sales are slipping this summer while the promo machine runs full-tilt for Katy Perry, who’s selling an updated Betty Page wet dream. Well, straight men still pull the budgetary levers at the major labels.

I was never fond of the smugly-named British band ‘Pop Will Eat Itself.’ As this creative-commercial cycle accelerates, however, I’m beginning to wonder if they were onto something. Adding momentum to this cycle is the fact that music went post-modern about 20 years ago. That is, sampling signified the gradual decline of truly new forms of pop music in favour of mixing original combinations of retro styles. If artists’ formulas weren’t made of old ingredients, it would be that much harder for executives to hack the recipe.

The ‘no rules’ artist to watch at this moment is Janelle Monae. She’s 24, she’s thoroughly disregarding anything that might be put on her as a female or a person of colour (in her own words: ‘I don’t have to do anything by default’), she’s got a big budget and she’s interesting. And–oh yes–she can sing. She can perform.

Andre 3000 and Big Boi of Outkast began working with her years back, and P. Diddy, of all people, has diverged from pop formula long enough to sign her and give her the kind of backing true artists only dream of in 2010.

Her trip is highly conceptual. Through a four-part suite, she’s reportedly telling the story of a robot named Cindi Mayweather who orchestrates an uprising in Metropolis. Her lyrics are so cryptic, however, that this storyline is barely apparent in the songs. At this early stage her output is coming across as a whole lot of disjointed concept, borrowed from many sources. If Fritz Lang doesn’t turn over in his grave at her shameless appropriation of his story, other visionaries like James Brown might. Virtually every song ends up a pastiche of the styles of several decades over the last century.

Melodically, the material is somewhat flat, the most memorable hooks lifted from elsewhere. Near the beginning of ‘Many Moons,’ a single from 2008’s Metropolis: The Chase Suite, she blatantly bites a riff from the Sesame Street pinball song we all know. After escaping the distraction of the very high budget of the ‘Many Moons’ video, it struck me that the most memorable moment of the song itself was that riff.

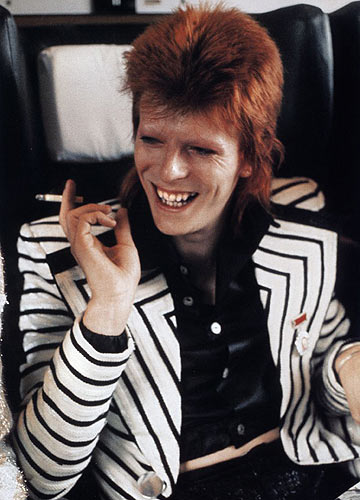

Selections from the new album, The ArchAndroid, include: ‘Cold War,’ its arresting single-shot video summoning the moment Sinead O’Connor shed a single tear for the camera in ‘Nothing Compares 2 U’; ‘Tightrope,’ with its main ‘on the scene’ hook lifted from ‘Sex Machine,’ (something she appeared to cop to as she donned a James Brown cape while performing it on David Letterman); ‘Sir Greendown,’ something like Shirley Bassey singing a version of ‘Moon River’; and ‘Make The Bus,’ like an outtake from David Bowie’s 70s trilogy produced by Brian Eno.

Another album track, ‘Locked Inside,’ feels good because it’s written over the chords of Stevie Wonder’s ‘Golden Lady’. It’s all crammed in there, cryptic and disorganized, from cabaret to hot jazz horns and 80s hip hop. And though it’s the work of an artist getting her bearings, both overdoing the concept and underdoing the original substance, she does appear to have the potential to change the game.

In order to keep that high budget record deal so she can mature creatively, it’s important that she have a bonafide hit sometime soon. And for that to happen the songs may have to fit into a framework that people understand a little more readily. There’s the catch-22: before the artist can ignore creative boundaries and lead the way, it seems she must first learn to simplify her writing. In days gone by labels could allow an artist several albums to reach a commercial stride. These days, it’s possible that other executives may be able to pinpoint what’s special about Monae early on and manufacture other acts that are capable of overtaking her. Hurry, Janelle, hurry and grow your garden!

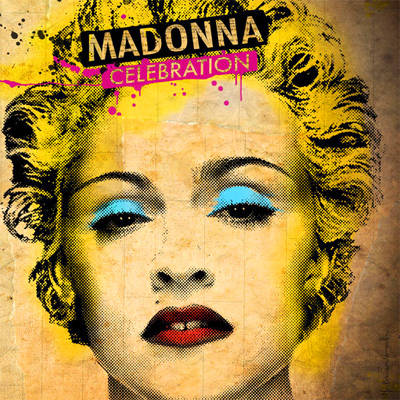

People In Your Neighbourhood

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Labels, Management, Singing, Writing on July 15, 2009

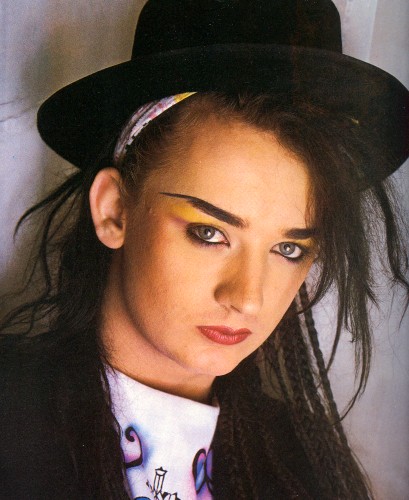

At the height of Culture Club’s success I remember people complaining that Boy George should have been able to make it solely on musical talent, without needing to resort to gimmickry…ie dressing in cosmopolitan drag. He was a talented writer and singer, but–consciously or unconsciously–he realized that audiences are not attracted to artists purely on the merit of their musical output.

We know this is true because there are endless examples of uniquely talented musicians that never garner a substantial following. That’s because what actually attracts us, as listeners, I believe, is an artist’s identity.

It’s true that this identity is built in part around the style and content of the songs, including the lyrics and the overall tone/sentiment. But for a star to be born, it’s critical that the music align properly with a host of other attributes, including the voice they were born with and the way they choose to use it; the physicality they were born with and how they choose to dress it up; how they move; and how they interview. The persona constructed with these tools needs to be instantly recognizable and compelling. (I won’t go so far as to say ‘appealing’, because there are plenty of celebrities that we love to hate.)

Speaking recently of the Supremes, Diana Ross wasn’t the lead singer of the group because she had the best voice in a technical sense. But her effervescent look and pastel-sounding voice combined to make her a compelling figure: she had instant identity.

Whether it’s the first few lines of a song, or a photo in a magazine spread, the audience needs to get a sense of the artist’s identity similar to the impressions we form of the people in our neighbourhoods we see around but haven’t had personal conversations with yet.

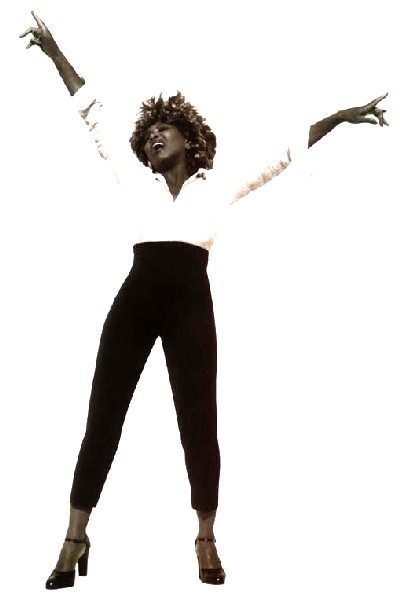

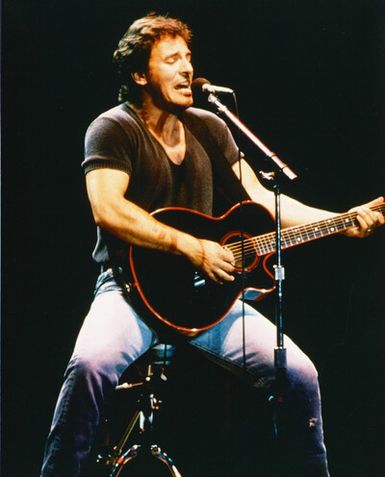

Here are some artists with identities so clear and compelling, whether we like them or not we all feel as though we know them from around.

All musicians are driven to make music. Those that are also driven to author every aspect of their public persona–from clothing to video treatments–end up having a lot less time to sleep but they have an edge over the rest, both in terms of career control and potential for success. That’s because most of us lack the ability to stand back and get a clear perspective on who we are, pinpoint what’s compelling about ourselves and amplify it.

Those who can’t must rely on industry executives’ abilities to look inside them and tailor the right persona…a rare feat in itself. If they get it wrong, the project will fail either because the identity won’t be compelling, or the artist won’t be able to carry an ill-fitting persona for very long before the audience sees through it.