Exclusive vs Inclusive Clubbing

Posted by Gavin Bradley in DJing on July 23, 2009

Have you ever noticed that there are two main kinds of clubbing experiences? Well there are…exclusive and inclusive. And from what I can tell they draw two different types of crowds for two different reasons.

Exclusive clubs rely on guest lists and dress codes to maintain that feeling of exclusivity. If you got in, you’ve met the club’s fabulousness quotient and you’ve been lifted above all that riffraff still waiting in line outside.

Studio 54 in late ’70s New York was the mother of all exclusive clubs. It was about decadent decor and lavish procession, seeing and being seen. Bianca Jagger rode in on a white horse once. It was the preferred club for celebrities to hold their parties at and any mortals lucky enough to get in would rub elbows with the stars and have stories to tell for the rest of their lives. The currency of the club was that rush of feeling like one of the chosen ones…and that could only happen because the rest of the world was excluded from the party.

While it would have been a sight to witness, I probably wouldn’t have actually had a good time at Studio 54 because in general I’m not into that exclusionary clubbing experience.

I like inclusive places where anyone can get in, wearing anything, without a guest list hookup. When you’ve got great music and no attitude, people come to dance. There’s an infectious happy energy created by diversity in a crowd. And you won’t find a lot of posers when people are truly there for the music.

In ’90s New York I had the pleasure of attending Body And Soul held at Club Vinyl. The legendary resident DJs were Francois K, Danny Krivit and Joe Claussell. The club was the after-after party to Saturday night…it began Sunday afternoon. No alcohol was served, just bottled water. Whatever the substances of choice were, usage was not overt. There really wasn’t even much of a light show. I just remember three stacks of speakers, a couple of stories high, facing a packed, sweaty, dark dancefloor. And every kind of person was there, absolutely going off to the music.

Late 80s warehouse parties and early 90s raves were inclusive events. Though the location was always mysterious, if you found the place you were welcomed to the party no matter who you were or what you looked like.

On the flipside, gay circuit parties in the late 90s were exclusive: only muscle marys with major disposable income need apply.

A great party that’s still going on in New York is an outdoor jam called the Soul Summit that takes place every Sunday through the summer in Brooklyn’s Fort Greene Park. It’s like an earthier, free outdoor version of Body And Soul. Diverse, positive and inclusive. These people are strictly about the music and they like it soulful and deep.

Toronto has its own outdoor sound system on summer Sundays called Promise. It’s free, the roster of guest DJs rotates, and you might hear anything from reggae to freestyle to funk to hardcore in one evening. It operates by word of mouth, moves around a bit but generally stays near Cherry Beach.

It’s full of hippies and ex-ravers, young couples with their dogs and kids, the odd soccer team…? Whoever hears the sound through the bushes arrives to find a happy and welcoming party by the water.

If you think about it, you can pretty much walk into any party and figure out in a few moments whether it’s an exclusive or inclusive environment. Usually if it’s exclusive I tend to walk back out.

People In Your Neighbourhood

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Labels, Management, Singing, Writing on July 15, 2009

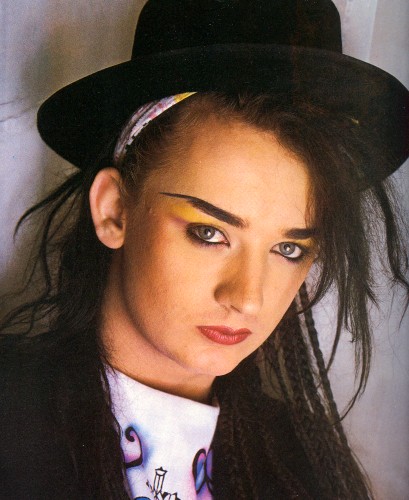

At the height of Culture Club’s success I remember people complaining that Boy George should have been able to make it solely on musical talent, without needing to resort to gimmickry…ie dressing in cosmopolitan drag. He was a talented writer and singer, but–consciously or unconsciously–he realized that audiences are not attracted to artists purely on the merit of their musical output.

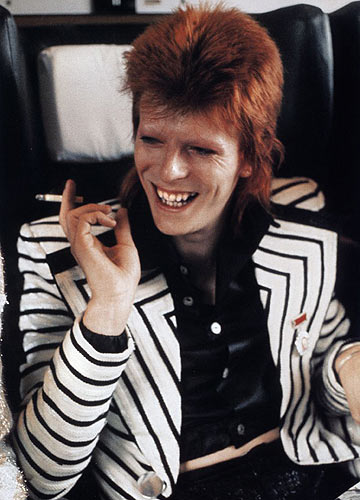

We know this is true because there are endless examples of uniquely talented musicians that never garner a substantial following. That’s because what actually attracts us, as listeners, I believe, is an artist’s identity.

It’s true that this identity is built in part around the style and content of the songs, including the lyrics and the overall tone/sentiment. But for a star to be born, it’s critical that the music align properly with a host of other attributes, including the voice they were born with and the way they choose to use it; the physicality they were born with and how they choose to dress it up; how they move; and how they interview. The persona constructed with these tools needs to be instantly recognizable and compelling. (I won’t go so far as to say ‘appealing’, because there are plenty of celebrities that we love to hate.)

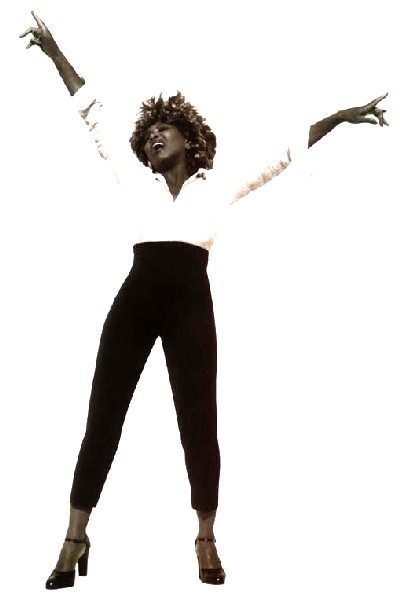

Speaking recently of the Supremes, Diana Ross wasn’t the lead singer of the group because she had the best voice in a technical sense. But her effervescent look and pastel-sounding voice combined to make her a compelling figure: she had instant identity.

Whether it’s the first few lines of a song, or a photo in a magazine spread, the audience needs to get a sense of the artist’s identity similar to the impressions we form of the people in our neighbourhoods we see around but haven’t had personal conversations with yet.

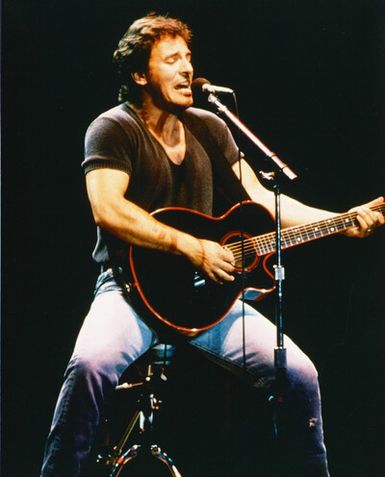

Here are some artists with identities so clear and compelling, whether we like them or not we all feel as though we know them from around.

All musicians are driven to make music. Those that are also driven to author every aspect of their public persona–from clothing to video treatments–end up having a lot less time to sleep but they have an edge over the rest, both in terms of career control and potential for success. That’s because most of us lack the ability to stand back and get a clear perspective on who we are, pinpoint what’s compelling about ourselves and amplify it.

Those who can’t must rely on industry executives’ abilities to look inside them and tailor the right persona…a rare feat in itself. If they get it wrong, the project will fail either because the identity won’t be compelling, or the artist won’t be able to carry an ill-fitting persona for very long before the audience sees through it.

Love Child: Songwriting Economy

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Radio, Writing on July 4, 2009

When you’ve written a good hook it’s natural to want to repeat it as much as possible. It’s also natural to assume that the goal, by the end of the song, is to leave the listener fully satiated.

But if they’re satiated, what’s the motivation to start the song over for another listen? And that’s what you want, isn’t it? A song people can’t get enough of?

Of course dancefloor producers and rock bands have explored the journey-within-a-song aesthetic to great effect, creating many masterpieces over five…seven…even ten minutes long. But if you’re learning to write and you want to reach a lot of people with your music, it pays to set aside the notion that a magnum opus will come out of you before you learn the craft of writing economically.

So, if there is a very special moment in a song, consider not repeating it. Focus instead on coming up with another great melodic moment somewhere else in the song, and don’t write extra verses just to beat the subject matter to death lyrically. Give the listener a reason to put your song on repeat.

When it comes to songwriting economy I can think of no better example than ‘Love Child’ by Diana Ross & The Supremes.

Clocking in at 2:59 the song is a good 10-20 seconds longer than many Motown singles, but that’s probably because there’s enough character and story development in there to write a screenplay.

Released in 1968, the song appeared at a time when writers other than mainstays Holland-Dozier-Holland were being brought into the Motown fold; a time when the label was making a point of moving from innocuous ‘going steady’ lyrics to more socially conscious subject matter.

‘Love Child’ tells the story of a girl who is refusing to take the chance of becoming pregnant by her boyfriend–asking him to wait until they’re married–because she herself was born to an unwed mother, suffering discrimination as a result. The notion of living with the shame of being a ‘love child’ is a bit dated now. But at the time it was edgy material, and the song retains a cooled-out stylistic timelessness.

The economy of the writing is astounding. In just a few sentences we find out who she is; what she and her mother went through; what her father did; what her boyfriend wants from her; what the baby they might have would go through; details around the argument they’re having; and that she knows she’ll always love her boyfriend even if she loses him over her non-negotiable stand:

Love Child

(Pamela Sawyer/R. Dean Taylor/Frank Wilson/Deke Richards)

Prechorus 1

You think that I don’t feel love, but what I feel for you is real love. In those eyes I see reflected a hurt, scorned, rejected…

Chorus 1

Love Child, never meant to be, Love Child, born in poverty, Love Child, never meant to be, Love Child, take a look at me

Verse 2

Started my life in an old cold run down tenement slum. My father left, he never even married mama. I shared the guilt my mama knew, so afraid that others knew I had no name

Prechorus 2

This love we’re contemplating, is worth the pain of waiting. We’ll only end up hating the child we may be creating

Chorus 2

Love child, never meant to be, Love Child, scorned by society, Love Child, always second best, Love Child, different from the rest

Break/Bridge

Hold on, hold on…Hold on, hold on…

Verse 3

I started school in a worn, torn dress that somebody threw out. I knew the way it felt to always live in doubt, to be without the simple things, so afraid my friends would see the guilt in me

Prechorus 3

Don’t think that I don’t need you. Don’t think I don’t want to please you. But no child of mine will be bearing the name of shame I’ve been wearing

Chorus 3

Love Child, Love Child, never quite as good, afraid, ashamed misunderstood

Tag

But I’ll always love you. Wait, won’t you wait now, hold on. I’ll always love you.

‘Love Child’ has no first verse. In an uncommon but inspired move, the writers decided to cut to the first pre-chorus after the song’s short intro. As the pre-chorus is a tension-builder, this serves to set an urgent tone immediately, as opposed to the methodical feeling of beginning with a verse, or giving the mystery away by beginning with the chorus.

Aside from a few poetic descriptive phrases like ‘old cold run down tenement slum’ and the outdated ‘scorned by society,’ the song is written in plain english. In the opening line (‘you think that I don’t feel love, but what I feel for you is real love’) there is no attempt to select ornate, profound-sounding language…but in a short series of single-syllable words we learn what’s happening under the surface: her boyfriend is trying to pressure her into having sex by accusing her of being emotionally unresponsive, while she asserts that the act of waiting to have sex is a manifestation of real love.

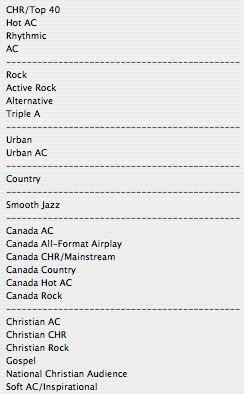

Because this song comes in at less than 3 minutes, and because each and every line is a hook unto itself, even maximizing opportunities to fill in the storyline in the choruses with phrases cleverly disguised as ad libs, it’s one of those singles that begs repeated plays. This is when radio happily puts a single into high rotation, and this is when an audience chooses to spend their time listening to a particular artist’s work…rather than the artist having to cajole them into it.

For Those About To Make An mp3…

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Engineering, Mixing, Production on June 22, 2009

…these guidelines will ensure that you don’t populate the web with awful sounding files.

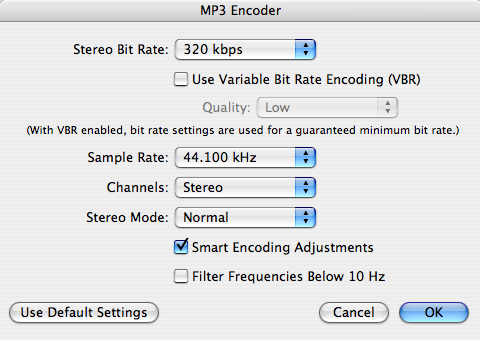

- Don’t use ‘Joint Stereo’. This saves marginally on file space by allowing the left and right channels to share information as necessary, which results in warbling treble.

- Don’t use ‘Variable Bit Rate (VBR)’. This allows the file quality to lower when there’s less complexity in the music, and again you can hear the treble change as the file quality shifts fluidly like this. Always use Constant Bit Rate (CBR).

- The Sample Rate needs to be 44.1, like a CD. Lower it and lose quality fast.

- The only thing you should play with if you want to create smaller files is the Bit Rate, and don’t go below 128. 320 is very close to CD quality, and since most of us have high speed access now we should always be using it.

- Do not make an mp3 of an mp3, or an mp3 of a CD that was burned from mp3s. This makes worse and worse sounding files (see below for why).

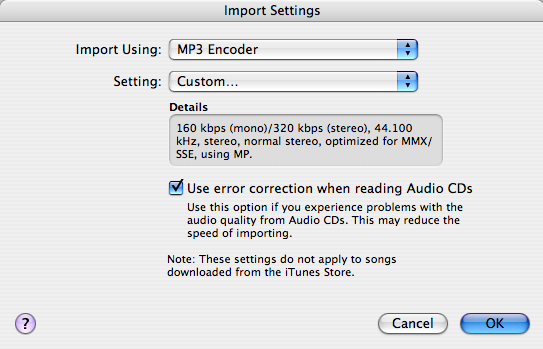

These guidelines go for whatever program you use for your mp3s. But to set this up in iTunes, open Preferences/Settings and click on the ‘Import Settings’ button. Where it says ‘Import Using:’ select the ‘MP3 Encoder’. Beside ‘Setting’ select ‘Custom…’

Then set things up this way:

In iTunes you do not want to check ‘Filter Frequencies Below 10 Hz’ because although we can’t hear bass that low, its absence does affect the impact of the sound we do hear. Check ‘Smart Encoding Adjustments’ though. Might as well be smart.

On another note…media files come in two types: ‘lossless’ (large files that capture all of the information (used for large-format print applications, store-bought CDs and DVDs) and ‘lossy’ (smaller files that approximate the sound or image, but are easier to share on the net).

So if you’re a graphic designer and you need high quality image files to print posters from, you use TIFF or EPS files…but if you’re designing for the web you use jpg or gif files. They’re not as visually clear, but on a small web page they look fine. What you don’t want to do is make a jpg of a jpg because the image will gradually degrade.

In audio, if you want to retain all of the information perfectly you use WAV, AIF or SD2 files (the highest quality file you can get from a standard CD is a 44.1 kHz stereo WAV/AIF file). But ever since file sharing began on the net, we’ve relied increasingly upon mp3, and mp4/AAC files.

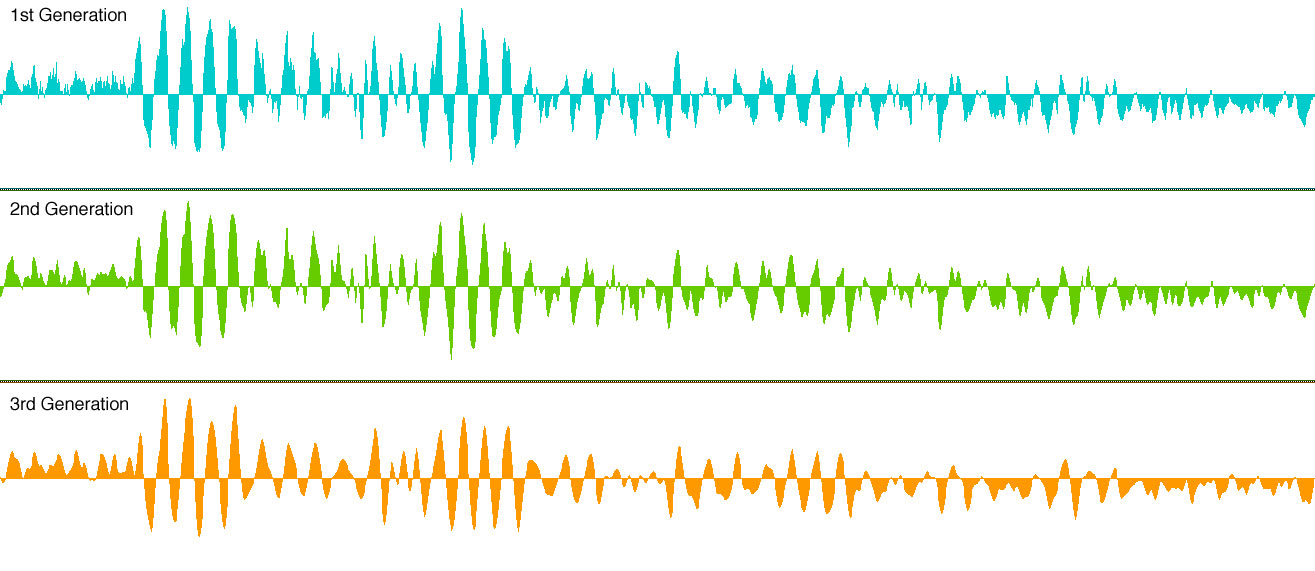

If you make an mp3 from a CD or WAV file with the settings described above, you’re getting something that is virtually indistinguishable from the original CD. But if you open that mp3 file to make changes to it (like edit the beginning and end of it) and then you save it again, you’re making an mp3 of an mp3…and that’s akin to repeatedly making a jpg of a jpg, losing information each time. Here’s what you get if you keep making lossy files of lossy files:

Below is what the sound wave looks like for the three passages you just heard…details in the wave get lost with each generation:

It’s especially important to be vigilant about this issue if you’re a producer who’s sampling off of mp3s to make your beats. Realize that when you’re done mixing your CD-quality WAV file, the first thing that’s going to happen is someone is going to make an mp3 of it. And then some of the elements in your track are going to lose impact because the source files were already mp3s.

The Cold-Warm Effect

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Production, Singing, Writing on June 18, 2009

After the sound of monophonic synthesizers, played by hand one note at a time, became commonplace on progressive rock recordings in the early 70s…

After people got used to hearing tapestries of synths triggered like clockwork by unfeeling sequencers and arpeggiators in the experiments of Kraftwerk through the mid 70s…

And after producer Giorgio Moroder pulled late-70s disco into the future by placing Donna Summer’s operetics over a pulsing synthetic backdrop on ‘I Feel Love’…

…Alison Moyet belted ‘Goodbye 70s’ over Vince Clark’s minimal synth and drum machine programming on Yaz’s 1981 debut album ‘Upstairs At Eric’s’.

Clark, the keyboard player and chief songwriter for a fledgling Depeche Mode, left the band after their debut album and formed Yaz (known in the UK as Yazoo). Clark’s working relationship with Moyet also imploded early on, leaving just two beautifully crafted Yaz albums. The detached lyrical attitude was new wave and the melodies were pure pop, but the juxtaposition of the warm human soul in Moyet’s ferociously large voice over top of Clark’s frigid production was a new level of what I call ‘cold-warm’ production.

‘Midnight’ is a great example of this style. After a naturally-paced acapella intro, the synth sequence begins without drama or fanfare. Emotionless and ruthlessly precise, it’s there solely to do the job of defining a framework of chords and rhythm under her voice. Her delivery is suddenly recontextualized: because the backdrop is icy cold, the heat of human breath against it is that much more apparent.

After Yaz, Moyet began a successful solo career and Clark formed Erasure with Andy Bell–whose vocal tone, it has been noted, is curiously similar to Moyet’s.

Enter Eurythmics. Dave Stewart and Annie Lennox had been making music together for some time, first in rock band The Tourists and then as Eurythmics, releasing their experimental but mostly organic (ie non-electronic) debut album ‘In The Garden’ in 1981.

But then they clued in on where Yaz, and other UK synth-based bands like The Human League and Heaven 17 were going and jumped in on their seminal ‘Sweet Dreams (Are Made Of This)’ album in 1983.

The liner notes on the 2005 reissues of the Eurythmics’ catalog discussed which drum machines and synths had been used, and also revealed that organic sounds–like drumming on glass bottles–were routinely weaved in. However, these were treated with effects so as to be camouflaged as part of the cold electronics. A manifesto of the pair’s directives was written on the wall of their studio, including the phrases ‘Tamla Motown,’ ‘Electronica’ and ‘Coldness’. So there it is: soul on ice.

On their best work–the fully electronic ‘Sweet Dreams’, ‘Touch’ and ‘Savage’ albums–Lennox’s soulful voice is generally the solitary human element sitting on top of the coldness. She even sonically evokes the visual of her warm breath meeting wintery cold in her trademark practice of peppering vocal performances with gutteral stabs of exhalation. Very occasionally another warm melodic element is chosen to create that same contrast against the pings and bleeps: the long trumpet solo on ‘The Walk’ and the violin lines of the British Philharmonic Orchestra on ‘Here Comes The Rain Again’.

‘Love Is A Stranger’ is a 3-minute pop song with a perfect balance of soul and circuitry.

Lennox pushed her experimentation with coldness further by developing a suitably cold image. Often labeled androgynous, I believe her main character, sporting an orange crew-cut, would be more accurately described as inhabiting a deadened sexuality. After having established that baseline, she was then in a position to play with the hypermasculine (dressing up as Elvis in the video for ‘Who’s That Girl’) or the hyperfeminine (her female character in the same video, or the split-personality cougar depicted on the ‘Savage’ concept album) as a way to critique, humorously, the traditionally accepted extremes of gender.

She also brought a detached, frigid air to many of her lyrics. On ‘Regrets’ she plays a bloodless character listing the chilling powers available to her: “I’ve got a dangerous nature, and my fist collides with your furniture…I’ve got a razor blade smile…fifteen senses are on my palette…I’m an electric wire and I’m stuck inside your head.” After establishing a consistent lack of emotion, lyrically, the slightest hint of tenderness in her lyrics would be magnified tenfold.

It must be said–because it’s not mentioned very often–that much of the groundwork for Lennox’ success was laid by Grace Jones. In fact Jones’ vocal licks and delivery, her ruthless lyrical style and her arty experimentation with androgyny right down to the signature crew cut were clearly recycled by Lennox in the early years of Eurythmics. What Jones lacked was commercial hooks in the songs, and what was special about the Eurythmics was the starkness of the electronic backdrop that Dave Stewart provided, which in my view couldn’t have more perfectly showcased the warmth of the human voice.