Archive for category Radio

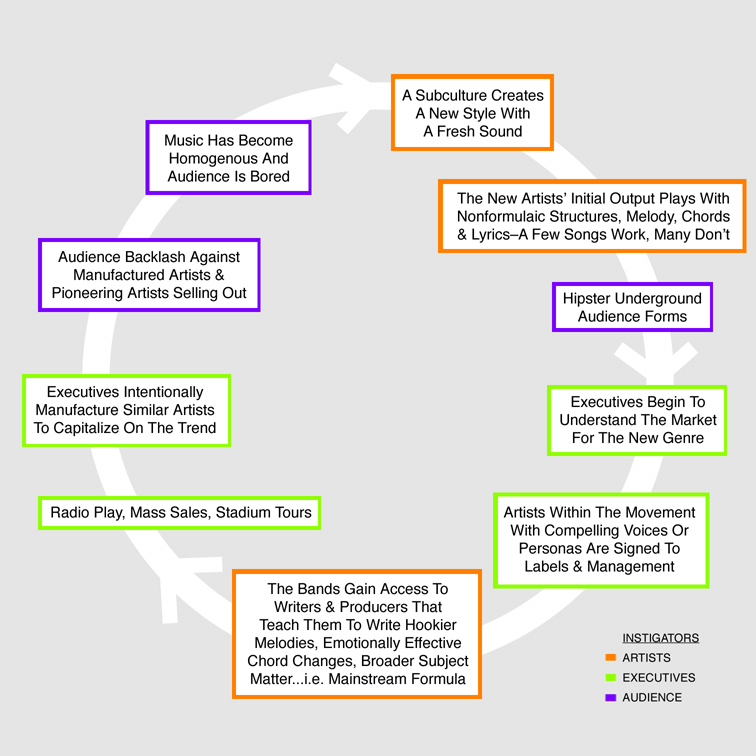

The Creative-Commercial Cycle: How Pop Eats Itself

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Labels, Management, Production, Radio, Writing on August 19, 2010

If it’s agreed that the following creative-commercial cycle occurs continuously in popular music…

…then there are a couple of things I find interesting. Namely, the process by which naturally compelling artists learn to create music with mass appeal, and the fact that this cycle seems to be speeding up as the executives get quicker at identifying and exploiting new trends.

For an example of the cycle, we can look at U2’s output. In the early 80s they had underground ‘alternative rock’ cool factor. The songs on their first two albums Boy and October were somewhat freeform. Melodies were cockeyed and noncommittal, lyrics never too direct. Bono’s voice and Edge’s guitar sound, together, supplied compelling personality. Steve Lillywhite’s production captured the band’s raw electricity without stylizing it.

War and The Unforgettable Fire followed, with ‘Sunday Bloody Sunday,’ ‘New Year’s Day’ and ‘Pride (In The Name Of Love)’ showing the first signs of a desire to write for radio. However, an inspired change in personnel brought a new depth to the sound of that fourth album: ambient visionary Brian Eno and roots musician Daniel Lanois were brought in to produce.

Not surprisingly, the subsequent writing on The Joshua Tree was significantly distilled. The straight-ahead stock chord changes and emotive melody of ‘With Or Without You’ as well as the clear, sweeping subject matter of ‘I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For’ and ‘Where The Streets Have No Name’ brought a mainstream audience to them as if by magnetic pull. If Eno and Lanois hadn’t purposely educated the band about mainstream pop writing, some form of growth-through-osmosis had happened as they opened up their creative circle.

Here’s a wordy section from ‘Drowning Man’ on War, followed by the confidence of the continuously building ‘With Or Without You’.

Since the watershed success of that album and the Rattle & Hum stadium tour–amid their core audience’s protests that the band had sold out–U2 has ridden out the last 20 years in various states of expectation-busting experimentation (Zooropa, The Passengers’ Original Soundtracks project) and pop duty fulfillment (All That You Can’t Leave Behind).

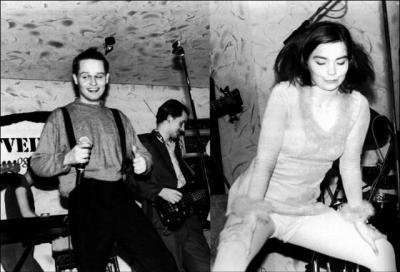

Bjork–who, incidentally, at first used her voice much like Bono had in the early 80s–first helmed Icelandic band Kukl, followed by The Sugarcubes. Her childlike voice and persona showed commercial promise amidst the disarray of the bands’ post-punk art-rock.

Teaming up with respected electronic producer Nellee Hooper, she emerged as a solo artist in 1993 with Debut, securing her place in pop history. The follow-up album was Post. ‘It’s Oh So Quiet,’ the big band single America loved to hate, was as straightforward as she would ever get before making her way back into ever-deeper experimental waters.

Compare the atonal rant from ‘Copy Thy Neighbour’ by Kukl with the soaring melody on the chorus of ‘Hyperballad’.

10,000 Maniacs is an interesting case that I made an effort to crack recently. I always had a like-hate relationship (as opposed to love-hate) with their In My Tribe, Blind Man’s Zoo and Our Time In Eden albums because I never quite understood how a band could sabotage moments of melodic virtuosity with such poorly considered arrangements. Or how such a compelling voice–meaning Natalie Merchant’s vocal instrument as well as the interesting angles she took on the songs’ subject matter–could be ruined by an equal helping of preachy condescension. As well, even after a string of five pop singles (‘Like The Weather,’ ‘What’s The Matter Here,’ ‘Trouble Me,’ ‘These Are Days’ and ‘Candy Everybody Wants,’) the band seemed to retain ‘alternative’ cred. Surely it couldn’t just have been based on their name.

A listen through their early recordings, reissued later on Hope Chest and The Wishing Chair, explained much. Like early U2 and Kukl, these songs are meandering stabs at writing, with hookless melodies, wordy, unclear lyrics and unremarkable chord changes. Also like Bono and Bjork, Merchant’s singular personality came through in her voice and the way she used it. 10,000 Maniacs guitarist Rob Buck, too, had an original style. Perhaps not as iconoclastic as Edge’s, but enough to show promise to a record company like Elektra. The band’s ‘alternative’ roots show in these recordings: in addition to the beginnings of their brand of quirky rock, we’re taken through painful world music experiments in Soca, Zouk and Dub Reggae.

‘Death Of Manolete’ from Hope Chest demonstrates the freedom of their wide-open creativity while the exquisite ‘Dust Bowl’ from Blind Man’s Zoo shows us the focus that took hold by the band’s second album with major label producer Peter Asher.

And so we have the artists, feeling around for something new to chew on, and the executives, racing to learn how to capitalize on a movement, a sound, an idea, a persona. They can’t exist without each other, so I don’t mean to imply that executives are the Cruella DeVilles of the world. But the crops need time to grow before the combine comes along to harvest. And in the age of the internet, traces of new artistic energy are identified and absorbed into the machine with breakneck acceleration.

One such ‘absorption cycle’ that makes me shudder is what occurred somewhere between 1995 and 2008, when Jill Sobule and Katy Perry each released a song called ‘I Kissed A Girl.’ Sobule’s song felt like the honest confession of a woman testing the fluidity of her sexuality. Perry’s felt like a market-researched ‘girls gone wild’ capitalization on straight mens’ fascination with girl-on-girl action. The sincere feminist perspective of artists like Sobule through the early 90s was officially absorbed into the machine when Simon Fuller auditioned British Barbie dolls for the Spice Girls. What was their mantra? ‘Girl Power’? Fast forward a decade, and it’s as though the feminist consciousness of the early 90s never existed. Lillith Fair sales are slipping this summer while the promo machine runs full-tilt for Katy Perry, who’s selling an updated Betty Page wet dream. Well, straight men still pull the budgetary levers at the major labels.

I was never fond of the smugly-named British band ‘Pop Will Eat Itself.’ As this creative-commercial cycle accelerates, however, I’m beginning to wonder if they were onto something. Adding momentum to this cycle is the fact that music went post-modern about 20 years ago. That is, sampling signified the gradual decline of truly new forms of pop music in favour of mixing original combinations of retro styles. If artists’ formulas weren’t made of old ingredients, it would be that much harder for executives to hack the recipe.

The ‘no rules’ artist to watch at this moment is Janelle Monae. She’s 24, she’s thoroughly disregarding anything that might be put on her as a female or a person of colour (in her own words: ‘I don’t have to do anything by default’), she’s got a big budget and she’s interesting. And–oh yes–she can sing. She can perform.

Andre 3000 and Big Boi of Outkast began working with her years back, and P. Diddy, of all people, has diverged from pop formula long enough to sign her and give her the kind of backing true artists only dream of in 2010.

Her trip is highly conceptual. Through a four-part suite, she’s reportedly telling the story of a robot named Cindi Mayweather who orchestrates an uprising in Metropolis. Her lyrics are so cryptic, however, that this storyline is barely apparent in the songs. At this early stage her output is coming across as a whole lot of disjointed concept, borrowed from many sources. If Fritz Lang doesn’t turn over in his grave at her shameless appropriation of his story, other visionaries like James Brown might. Virtually every song ends up a pastiche of the styles of several decades over the last century.

Melodically, the material is somewhat flat, the most memorable hooks lifted from elsewhere. Near the beginning of ‘Many Moons,’ a single from 2008’s Metropolis: The Chase Suite, she blatantly bites a riff from the Sesame Street pinball song we all know. After escaping the distraction of the very high budget of the ‘Many Moons’ video, it struck me that the most memorable moment of the song itself was that riff.

Selections from the new album, The ArchAndroid, include: ‘Cold War,’ its arresting single-shot video summoning the moment Sinead O’Connor shed a single tear for the camera in ‘Nothing Compares 2 U’; ‘Tightrope,’ with its main ‘on the scene’ hook lifted from ‘Sex Machine,’ (something she appeared to cop to as she donned a James Brown cape while performing it on David Letterman); ‘Sir Greendown,’ something like Shirley Bassey singing a version of ‘Moon River’; and ‘Make The Bus,’ like an outtake from David Bowie’s 70s trilogy produced by Brian Eno.

Another album track, ‘Locked Inside,’ feels good because it’s written over the chords of Stevie Wonder’s ‘Golden Lady’. It’s all crammed in there, cryptic and disorganized, from cabaret to hot jazz horns and 80s hip hop. And though it’s the work of an artist getting her bearings, both overdoing the concept and underdoing the original substance, she does appear to have the potential to change the game.

In order to keep that high budget record deal so she can mature creatively, it’s important that she have a bonafide hit sometime soon. And for that to happen the songs may have to fit into a framework that people understand a little more readily. There’s the catch-22: before the artist can ignore creative boundaries and lead the way, it seems she must first learn to simplify her writing. In days gone by labels could allow an artist several albums to reach a commercial stride. These days, it’s possible that other executives may be able to pinpoint what’s special about Monae early on and manufacture other acts that are capable of overtaking her. Hurry, Janelle, hurry and grow your garden!

Love Child: Songwriting Economy

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Radio, Writing on July 4, 2009

When you’ve written a good hook it’s natural to want to repeat it as much as possible. It’s also natural to assume that the goal, by the end of the song, is to leave the listener fully satiated.

But if they’re satiated, what’s the motivation to start the song over for another listen? And that’s what you want, isn’t it? A song people can’t get enough of?

Of course dancefloor producers and rock bands have explored the journey-within-a-song aesthetic to great effect, creating many masterpieces over five…seven…even ten minutes long. But if you’re learning to write and you want to reach a lot of people with your music, it pays to set aside the notion that a magnum opus will come out of you before you learn the craft of writing economically.

So, if there is a very special moment in a song, consider not repeating it. Focus instead on coming up with another great melodic moment somewhere else in the song, and don’t write extra verses just to beat the subject matter to death lyrically. Give the listener a reason to put your song on repeat.

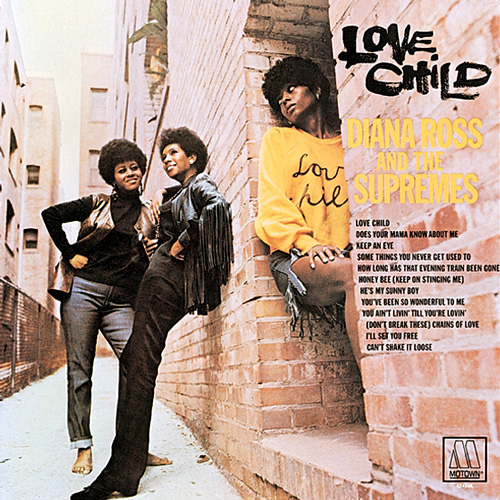

When it comes to songwriting economy I can think of no better example than ‘Love Child’ by Diana Ross & The Supremes.

Clocking in at 2:59 the song is a good 10-20 seconds longer than many Motown singles, but that’s probably because there’s enough character and story development in there to write a screenplay.

Released in 1968, the song appeared at a time when writers other than mainstays Holland-Dozier-Holland were being brought into the Motown fold; a time when the label was making a point of moving from innocuous ‘going steady’ lyrics to more socially conscious subject matter.

‘Love Child’ tells the story of a girl who is refusing to take the chance of becoming pregnant by her boyfriend–asking him to wait until they’re married–because she herself was born to an unwed mother, suffering discrimination as a result. The notion of living with the shame of being a ‘love child’ is a bit dated now. But at the time it was edgy material, and the song retains a cooled-out stylistic timelessness.

The economy of the writing is astounding. In just a few sentences we find out who she is; what she and her mother went through; what her father did; what her boyfriend wants from her; what the baby they might have would go through; details around the argument they’re having; and that she knows she’ll always love her boyfriend even if she loses him over her non-negotiable stand:

Love Child

(Pamela Sawyer/R. Dean Taylor/Frank Wilson/Deke Richards)

Prechorus 1

You think that I don’t feel love, but what I feel for you is real love. In those eyes I see reflected a hurt, scorned, rejected…

Chorus 1

Love Child, never meant to be, Love Child, born in poverty, Love Child, never meant to be, Love Child, take a look at me

Verse 2

Started my life in an old cold run down tenement slum. My father left, he never even married mama. I shared the guilt my mama knew, so afraid that others knew I had no name

Prechorus 2

This love we’re contemplating, is worth the pain of waiting. We’ll only end up hating the child we may be creating

Chorus 2

Love child, never meant to be, Love Child, scorned by society, Love Child, always second best, Love Child, different from the rest

Break/Bridge

Hold on, hold on…Hold on, hold on…

Verse 3

I started school in a worn, torn dress that somebody threw out. I knew the way it felt to always live in doubt, to be without the simple things, so afraid my friends would see the guilt in me

Prechorus 3

Don’t think that I don’t need you. Don’t think I don’t want to please you. But no child of mine will be bearing the name of shame I’ve been wearing

Chorus 3

Love Child, Love Child, never quite as good, afraid, ashamed misunderstood

Tag

But I’ll always love you. Wait, won’t you wait now, hold on. I’ll always love you.

‘Love Child’ has no first verse. In an uncommon but inspired move, the writers decided to cut to the first pre-chorus after the song’s short intro. As the pre-chorus is a tension-builder, this serves to set an urgent tone immediately, as opposed to the methodical feeling of beginning with a verse, or giving the mystery away by beginning with the chorus.

Aside from a few poetic descriptive phrases like ‘old cold run down tenement slum’ and the outdated ‘scorned by society,’ the song is written in plain english. In the opening line (‘you think that I don’t feel love, but what I feel for you is real love’) there is no attempt to select ornate, profound-sounding language…but in a short series of single-syllable words we learn what’s happening under the surface: her boyfriend is trying to pressure her into having sex by accusing her of being emotionally unresponsive, while she asserts that the act of waiting to have sex is a manifestation of real love.

Because this song comes in at less than 3 minutes, and because each and every line is a hook unto itself, even maximizing opportunities to fill in the storyline in the choruses with phrases cleverly disguised as ad libs, it’s one of those singles that begs repeated plays. This is when radio happily puts a single into high rotation, and this is when an audience chooses to spend their time listening to a particular artist’s work…rather than the artist having to cajole them into it.

To Sign Or Not To Sign

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Labels, Management, Publishing, Radio on June 11, 2009

In 2000 Courtney Love made a speech at a music conference. She got out her calculator and demonstrated what happens when a band signs a dream deal with a major label and has a hit album: the label makes an average of $6.6 million and the band makes an average of $0. The way things are structured in those deals, all of the costs of recording and promoting an album are passed back to the artist, and unless the band has multiple hit albums in a row they don’t actually make money.

This is not to say that the band isn’t living a suitably Hollywood lifestyle–touring and enjoying the trimmings of success–or that they might not benefit in the long run from having their identity erected to ‘household name’ status above the deafening din of all of the other aspiring musicians in the world. The major labels have built networks of promotional resources around themselves precisely for that purpose.

However, almost ten years after Love’s math class, the sea change in the music industry has lumbered forward. File sharing has won: physical product and the ‘brick-and-mortar’ stores that stock it are no longer necessary. All the filler labels used to cram onto CD-length albums is systematically ignored now that legal and illegal digital downloads are the norm. The majors have eaten up the rosters of even more independent boutique labels, destroying the influence of some of the innovative thinkers of those startups in an attempt to eliminate street-level competition. Sony and BMG merged, bringing the major label count down to four…that is, four clumsy multinational giants plagued with red tape and corporate approval hierarchies in a business that is utterly out of touch with ‘what the kids want’ because gut-level instincts have given way to copycat marketing models.

Essentially, it’s become common knowledge among insiders that for the foreseeable future, the major labels are going to be good for one type of music: music mass-marketed to 11-year old American or British girls. The artists doing that kind of music are often primarily concerned with fame, so they’re not thinking much about the money, assuming it will follow. They will rarely make a cut of the most potentially lucrative income source–writing royalties–because the labels will bring in professional writers who will come up with commercially viable material…or at least material that the radio stations will throw their support behind when they see writers with a track record of radio hits in the credits.

The labels all have sister companies in the music publishing world (Sony has Sony ATV Publishing; Warner has Warner-Chappell Publishing; EMI has EMI Music Publishing) that represent hit-making writers, and the cut those companies make gets routed back into the machine. It is true that often, however, the artist’s manager will insist that their non-writing artist come up with a line or two in a verse so that they’ll be cut in to the royalties at least in a minor way…and with their name in those credits, they’ll be perceived by fans as a singer-songwriter. (And this eventually leads to non-writing artists being offered lucrative publishing contracts, if their records are selling well.)

If you’re doing music aimed at anyone other than tweens, it’s probably a safer bet to stay indie, own everything and work hard to cultivate a solid grassroots fanbase. At this point in time, the majors are hemorrhaging money, so they expect artists with loftier musical ambitions to have done their own ‘artist development’…ie come up with their own image and styling; work out the details of their stage show; write some hit songs and grow an audience. So, ironically, if you do find yourself in the middle of a bidding war between the majors you may realize there’s not much more they can do for you. You might as well keep 100% of your profits rather than turn over 50-90% of your profits to somebody who didn’t show their support by investing in your potential earlier on.

There is no one ‘evil person’ at the helm of all of this financial deception. Artists are often focused on making their music and consider themselves not particularly business-minded, so they ignore the work they need to do to educate themselves.

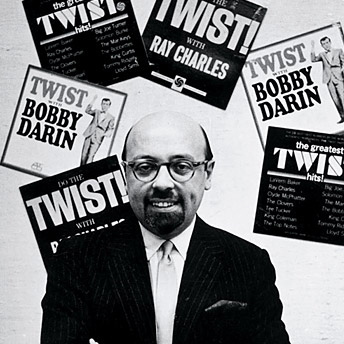

Many execs at labels and publishing companies are failed artists, or people who dreamed of being artists but never believed in themselves enough to give it a real shot. They want to stay involved in the industry, for the love of music or the cool factor, but how many execs could possibly have the instincts of industry legends like Atlantic Records founder Ahmet Ertegun, a man whose understanding and raw passion for music led him to build a diverse stable of equally legendary artists?

These days there are so many jobs on the line in these multinational record companies, risk-taking of any kind has consequences…hence the constant references to existing successes: ‘make a track like Bleeding Love by Leona Lewis.’ And the writers and producers all scamper off to study how the reference song is constructed, coming back with paler and paler imitations; further and further from what a hit song is supposed to be: an epiphany.

It’s a simple fact of the economy that growing a band on a global scale over a series of albums is now financially impossible. So, as Howard Jones would say, no one is to blame. I suppose you could waste your time blaming the forward march of technology, specifically mp3 compression and high-speed internet, the way the advent of sampling was once demonized. But industry guru Bob Lefsetz, for example, trumpets on a daily basis in his blog that the majors are on their last legs because they constantly miss the boat by fighting technology rather than finding ways to capitalize on it. He also repeats relentlessly: be a good, original musician; write good, original songs; do it because you love it and not because you’re looking to get rich. In other words, Build It And They Will Come.

I think most musicians commit to their vocation at an early age with the erroneous belief that a good song by someone with a great voice becomes a hit because everybody in the industry goes out of their way to make it so in the name of sharing exceptional new music. Most music fans who are industry outsiders exist their whole lives believing that this is so. They may have heard that the entertainment industry is full of sharks, or that it’s a hustle, but people rarely hear concrete explanations of shady practices.

A few things to think about when considering signing with a label, publishing company or manager:

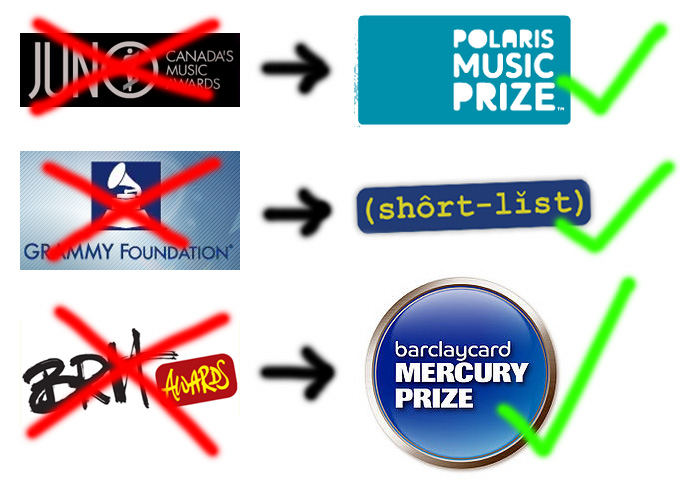

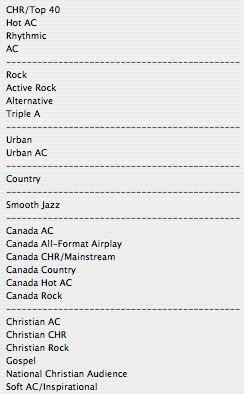

– Most radio stations are corporate entities now, often with multinational parent companies, and they have strict ‘formats’ detailing specific parameters (style, length, song structure) for what they play. The major labels have departments that feed the stations with material, and the stations trust the labels to bring content their listeners will be excited about. If you go the indie route, expect to pay an independent radio promoter several thousand dollars per month, per song, to try to get your material played on a specific format. The success rate for the investment is lower than if you are with a label. Material rarely gets in the door without a promoter. Whether radio is important anymore, with YouTube promoting most music, is another discussion entirely.

– If you do not live in the country where the head office of the label or publishing company you’re interested in is located, you will be trying to attract the attention of executives who have limited power over their artists’ destinies. In other words, if you sign with EMI in any country other than the UK or you sign with Universal, Warner or Sony in any country other than the US, your music will never be released in other countries unless the head offices there can be persuaded to back you as well. Writers signed to the offices of major publishing companies in countries other than the US or UK have their material pitched for use in movies, television and ads after domestic writers’ material is pitched as the head office stands to make less of a cut on foreign writers’ material.

– It’s critical to get the right fit: if you sign to the biggest label or publishing company because of their clout, and the individuals working at that office are not particularly excited about your music, you may find your project constantly blocked or shelved. Then it’s a waiting game to be released from your contract so your career can move forward. It’s also not unheard of for labels to sign artists with no intention of putting out their music…rather, the goal was to eliminate competition in the genre of one of the company’s existing artists.

– The same goes for managers. If you sign to the most powerful manager in your city–paying them 20% of your income for a period of years–make sure that they’re interested enough in your career that you are a priority for them. If that manager has another artist that blows up worldwide, you may find your needs ignored. It’s often better to be self-managed than managed by the wrong person.

– Because of their unique position negotiating contracts between parties in the industry, music lawyers know most of the players…be they labels, managers, publishers, producers, artists or writers. Often lawyers will help people network with each other, but watch out for biases and vested interests.

– Owning all of your publishing on a hit song can be very lucrative, however owning 100% of a song that isn’t being pushed to the right artists or advertisers is owning one hundred percent of nothing. The right publisher can help you make a living by pitching your material and setting up writing opportunities with artists. However if a television series is looking to use one of your songs, for example, they must clear its use with all parties who own a share. The more parties involved and the bigger the publishers, the more red tape…making it too much of a hassle for some agencies to bother with.