Archive for category Production

The Cold-Warm Effect

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Production, Singing, Writing on June 18, 2009

After the sound of monophonic synthesizers, played by hand one note at a time, became commonplace on progressive rock recordings in the early 70s…

After people got used to hearing tapestries of synths triggered like clockwork by unfeeling sequencers and arpeggiators in the experiments of Kraftwerk through the mid 70s…

And after producer Giorgio Moroder pulled late-70s disco into the future by placing Donna Summer’s operetics over a pulsing synthetic backdrop on ‘I Feel Love’…

…Alison Moyet belted ‘Goodbye 70s’ over Vince Clark’s minimal synth and drum machine programming on Yaz’s 1981 debut album ‘Upstairs At Eric’s’.

Clark, the keyboard player and chief songwriter for a fledgling Depeche Mode, left the band after their debut album and formed Yaz (known in the UK as Yazoo). Clark’s working relationship with Moyet also imploded early on, leaving just two beautifully crafted Yaz albums. The detached lyrical attitude was new wave and the melodies were pure pop, but the juxtaposition of the warm human soul in Moyet’s ferociously large voice over top of Clark’s frigid production was a new level of what I call ‘cold-warm’ production.

‘Midnight’ is a great example of this style. After a naturally-paced acapella intro, the synth sequence begins without drama or fanfare. Emotionless and ruthlessly precise, it’s there solely to do the job of defining a framework of chords and rhythm under her voice. Her delivery is suddenly recontextualized: because the backdrop is icy cold, the heat of human breath against it is that much more apparent.

After Yaz, Moyet began a successful solo career and Clark formed Erasure with Andy Bell–whose vocal tone, it has been noted, is curiously similar to Moyet’s.

Enter Eurythmics. Dave Stewart and Annie Lennox had been making music together for some time, first in rock band The Tourists and then as Eurythmics, releasing their experimental but mostly organic (ie non-electronic) debut album ‘In The Garden’ in 1981.

But then they clued in on where Yaz, and other UK synth-based bands like The Human League and Heaven 17 were going and jumped in on their seminal ‘Sweet Dreams (Are Made Of This)’ album in 1983.

The liner notes on the 2005 reissues of the Eurythmics’ catalog discussed which drum machines and synths had been used, and also revealed that organic sounds–like drumming on glass bottles–were routinely weaved in. However, these were treated with effects so as to be camouflaged as part of the cold electronics. A manifesto of the pair’s directives was written on the wall of their studio, including the phrases ‘Tamla Motown,’ ‘Electronica’ and ‘Coldness’. So there it is: soul on ice.

On their best work–the fully electronic ‘Sweet Dreams’, ‘Touch’ and ‘Savage’ albums–Lennox’s soulful voice is generally the solitary human element sitting on top of the coldness. She even sonically evokes the visual of her warm breath meeting wintery cold in her trademark practice of peppering vocal performances with gutteral stabs of exhalation. Very occasionally another warm melodic element is chosen to create that same contrast against the pings and bleeps: the long trumpet solo on ‘The Walk’ and the violin lines of the British Philharmonic Orchestra on ‘Here Comes The Rain Again’.

‘Love Is A Stranger’ is a 3-minute pop song with a perfect balance of soul and circuitry.

Lennox pushed her experimentation with coldness further by developing a suitably cold image. Often labeled androgynous, I believe her main character, sporting an orange crew-cut, would be more accurately described as inhabiting a deadened sexuality. After having established that baseline, she was then in a position to play with the hypermasculine (dressing up as Elvis in the video for ‘Who’s That Girl’) or the hyperfeminine (her female character in the same video, or the split-personality cougar depicted on the ‘Savage’ concept album) as a way to critique, humorously, the traditionally accepted extremes of gender.

She also brought a detached, frigid air to many of her lyrics. On ‘Regrets’ she plays a bloodless character listing the chilling powers available to her: “I’ve got a dangerous nature, and my fist collides with your furniture…I’ve got a razor blade smile…fifteen senses are on my palette…I’m an electric wire and I’m stuck inside your head.” After establishing a consistent lack of emotion, lyrically, the slightest hint of tenderness in her lyrics would be magnified tenfold.

It must be said–because it’s not mentioned very often–that much of the groundwork for Lennox’ success was laid by Grace Jones. In fact Jones’ vocal licks and delivery, her ruthless lyrical style and her arty experimentation with androgyny right down to the signature crew cut were clearly recycled by Lennox in the early years of Eurythmics. What Jones lacked was commercial hooks in the songs, and what was special about the Eurythmics was the starkness of the electronic backdrop that Dave Stewart provided, which in my view couldn’t have more perfectly showcased the warmth of the human voice.

Breakin’ Dishes: Capturing Sound Not So Perfectly

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Production on June 7, 2009

When somebody drops a glass or breaks a plate in the apartment next door, you know it’s happening for real–and not in a surround-sound movie they’re watching–because what we can capture on disc is still slightly lower quality than real life sound.

Since the first recordings made on cylinders in the late 1800s we’ve always pressed forward, unquestioningly, in our efforts to close the gap between ‘live and memorex’. Technologists, engineers and audiophiles have fought tirelessly to further extend the frequency range, dynamics and resolution of recordings. In the late 80s the jump to digital recording brought us infinitely closer to being able to reproduce sound without colouration of any kind, and science continues to improve upon the resolution of digital with the goal, I suppose, of having there be no discernable difference between real and reproduced sound.

This has been amazing for action movies. In some instances crisp, clear recordings with deep bass, pristine treble, wide spatial staging and infinite dynamic range should be the goal. But there is also a powerful group of mostly old-school music producers–the David Foster types, the Nashville types–that in my opinion have chosen to use the widescreen ‘colourless’ nature of digital to strip mainstream recordings of much of their character.

Looking back on pop culture over the last hundred years, some of what we hold dearest is that which we can’t quite ‘touch’…that which is partially obscured because it wasn’t captured realistically.

When we watch a black and white movie from the 1930s, a technicolor movie from the 1950s, or even a film shot on washed out Kodakchrome/Eastman stock from the 1970s, we’re losing ourselves in a world that is not quite our own…it’s a romanticized version of life brought to us in part due to a lack of honest colour information.

Similarly, when we listen to classic Motown, with its boxy sounding drums, distorted tambourines and general sonic blurriness, we’re transported to that sweaty basement in Detroit where players and singers delivered magic. And it’s not just nostalgic in retrospect. I maintain that it was already full of nostalgia when it first hit the radio precisely because it didn’t sound like real life: the very character of the sound stoked our collective imagination as to where this musical spirit was coming from.

If music is a window into other peoples’ real and imaginary worlds, why is there so often a de facto assumption that we even want it to sound true-to-life? And, once it’s possible to record sound at real-life resolutions, does that mean we’ll cease to experience decade-specific nostalgia as, moving forward, sound is always perfectly colourless?

I always tend to appreciate the planned or accidental limitation of sound quality, like a good pair of distressed jeans. I don’t feel that the most expensive microphone, the biggest mixing desk, or the greatest clarity and sonic detail should always be the goal. Capturing a moving performance should be first, and if a lower end microphone is all that was around when it happened, I don’t believe the artist should re-perform it on a $17k Neumann tube mic. In fact maybe a Fisher Price microphone should be plugged in now and again to see what will happen.

Some examples of intentionally and unintentionally ‘distressed’ recordings through the ages:

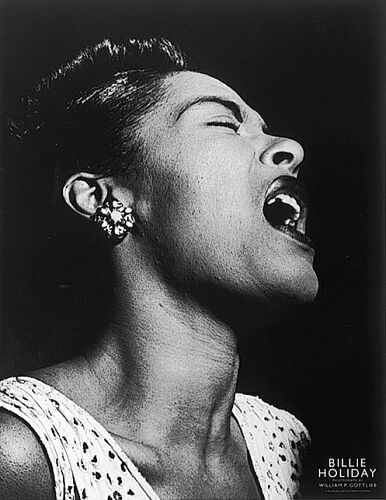

1. Billie Holiday’s 1935 recording ‘It’s Too Hot For Words’ was of course cut on a shellac disc using relatively primitive equipment. The dated style of the recording–the distortion and lack of bass and treble information–renders her forever untouchable, a tragic legend.

2. On ‘Strangers,’ the third track on Portishead’s 1994 groundbreaking debut disc ‘Dummy’, after a full frequency sonic barrage of an intro we plunge unexpectedly into what appears to be an improvised demo jam made on a handheld cassette recorder. Muted, distorted and noisy, Adrian Utley’s soulful jazz electric supports some of Beth Gibbons’ most shimmering vocal moments. This section of the song may in fact have been laboured over on high end recording equipment and then played back through a distorted guitar amp to achieve this effect…we may never know. By verse 2 we’re back in 1994 standards of high definition audio.

3. Throughout the 1990s layering vinyl surface noise over highly produced rap, R&B and pop was a common move to get back some of the nostalgia that seemed to be lacking on pristine digital recordings. 1996’s ‘No Love’ by Erykah Badu demonstrates the tactile feel of vinyl, as well as an intro section where the bass and treble are also filtered out of the music to make it sound lo-fi. When the track kicks in (and the filters are removed) note that the quality of the instruments is uncompromised by the vinyl pops we hear over top. This gave 1990s recordings a different feel than old recordings on actual damaged vinyl, because each click or pop on a record would actually distort the sound quality of the musical elements as it happened.

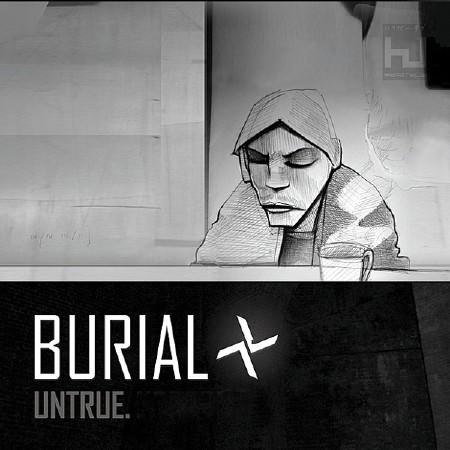

4. UK dubstep producer Burial puts down a bed of heavy, stuttering beats. On that he places a wax paper layer of lush, filmic ambient pads. Next, he sprinkles obscure mix-and-match R&B acapellas, filtering out the treble to create lyrical ambiguity. Finally he wraps the whole thing in a layer of sonic gauze using an expanded palette of crackle, ranging from standard vinyl crackle and tape hiss to rustling sounds and recordings of fire. The result, heard here on a drumless segue after ‘Shell Of Light’ on his 2008 album ‘Untrue’, is something like witnessing a merciful event through a frosted window.

These are all analog methods of bringing character to recordings: the limitations of vinyl, tape and guitar amps. But in the early part of this century we’ve seen some indication that producers will continue to time-stamp recordings by beginning to find useable limitations within the digital realm. For example, the glassy digitized sound of low quality mp3s has inspired some producers (most notably Mirwais, who produced Madonna’s ‘Music’ and ‘American Life’ albums…and of course Daft Punk) to apply similar lo-fi digital effects to vocals and music loops.

This type of experimentation gives me hope, in the digital age, that we won’t be listening to the silky smooth sound of David Foster muzak for the rest of eternity.

Having A Production Sound: Thomas Dolby

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Production on June 1, 2009

As a kid in the early 80s when I heard brand new ear candy on the radio I waited for the 411 from the announcer at the end of the song, scraped together some coin, grabbed my bike from the garage and rushed to the record store to get that hot pressed wax in hand. Some of the most urgent bike rides occurred after hearing these songs:

In order, you’re listening to the haunting synth pad intro of Foreigner’s ‘Waiting For A Girl Like You’ followed by the rock-funk atmosphere of ‘Urgent’ (another single from the same album), then the new wave whip-cracking of ‘New Toy’ by Lene Lovich and finally the tight slab of synth-funk that is Thomas Dolby’s ‘She Blinded Me With Science’.

I like all kinds of music but something about synthetic textures, from classic Pink Floyd to current Electro, has always held extra-deep excitement. Checking the liner notes 20 years later I realized there was no coincidence that these songs pressed similar buttons for me: they were all touched by Thomas Dolby’s electronics.

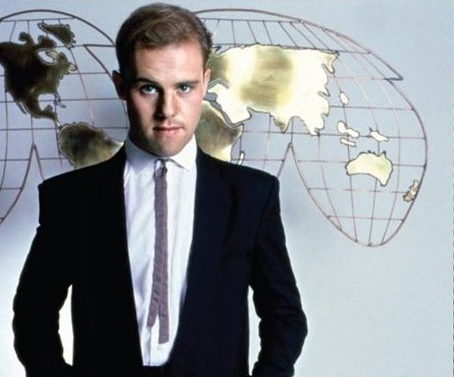

For a moment in the early 80s Thomas Dolby exemplified the potential of modern synthesized pop. On one side he played keyboards and programmed drum machines for mainstream rock bands like Foreigner, on the other he was called in to write and produce for underground phenomena like Lene Lovich.

Born Thomas Robertson, he acquired the ‘Dolby’ nickname in high school when fellow students mocked his obsession with his tape recorder. (Dolby Laboratories later filed suit against him.) When it came time to launch his solo career, he sampled british mad professor television personality Magnus Pike for ‘She Blinded Me With Science’, and was then photographed running from an ancient mainframe computer in full science teacher garb for the cover of the ‘Blinded By Science’ EP. The debut album that followed was titled ‘The Golden Age Of Wireless,’ in reverence for the magic of early radio, vaccuum tubes and all. Even with his unabashed romanticization of all things geeky, however, he escaped total nerddom by maintaining an edgy new wave leaning at all times.

Dolby certainly had a clear identity–lyrically, vocally and imagewise–but what was most remarkable was the way he asserted his identity within his production sound. I don’t know what brands of synthesizers and drum machines he favoured, but the choices he made with his sounds were unmistakable. Keyboards were haunting and drums were at once synthetic and funk-infused. Not everything was electronic. Guitar, bass and real drums were weaved in tastefully. His output carved out a singular, stylized sonic niche…he achieved a goal every producer aspires to.

Addiction: Fred Everything ft. Wayne Tennant – ‘Mercyless’

Posted by Gavin Bradley in DJing, Production on May 19, 2009

Wayne Tennant was the lead singer of Toronto funk band God Made Me Funky, then he moved to Montreal, started recording some solo work and spent some time playing Morocco and recording in the UK.

He’s done a collab with Montreal deep house producer Fred Everything for Fred’s album ‘Lost Together’ (Om Records). The track is called Mercyless…the single hit #2 this week on Traxsource…the only soulful house online store that matters. Tastemaker DJ/producer Osunlade also has it in his top ten right now.

Here’s a sampler of the mixes on the single. In order: the original LP mix, then the deeper Fred Everything & Olivier Desmet Remix, then the smooth AtJazz remix.

It’s a slow-burn. I liked it on first listen…I was addicted to it after a few. Wayne’s solo EP is coming out this summer.

Emotional Utterances

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Production, Singing on May 15, 2009

Some singer, at some point, must have naturally began adding a breathy ‘h’ to the ends of words. And some producer must have heard it and realized that this makes singers sound like they’re getting emotional. And when a listener hears the singer getting emotional, they in turn get emotional. That’s good for business, when you’re in the business of making people feel!

I’ll show you what I mean…check out Kelly Clarkson adding a big ‘h’ to the end of almost every line in the first verse of ‘My Life Would Suck Without You’. I’m using the Chris Ortega mix because the vocal is upfront:

This reminds me of the way marketing has developed into a science in the 21st century. Less gut and more tried-and-true, market-researched technique. Producers, myself included, are hyperconscious of ways that we can bring emotion to a song by manipulating the singer’s performance on a syllable-by-syllable basis. (That’s if the singer doesn’t already do it naturally.) It’s pretty much on the checklist that’s been created by the Idol franchise for what a good singer needs to be able to do. At the McDonald’s of the music world, they ask ‘would you like breath with that’?

Hey, it works, and there’s nothing wrong with it…but I prefer it when emotional utterances come out naturally in the performance rather than being pulled from a palette of what we now know works. I’m sure Otis Redding didn’t pre-meditate what he was going to utter in between syllables…even if he became aware of his own arsenal of signature vocal tricks. Do we know a bit too much now about how things work? When you’re really feeling what you’re singing, you don’t have to design how you’re going to deliver each part of it.