Archive for category Creative

Platinum Hit: Under The Hood Of The Music Industry

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Business, Creative, Labels, Publishing, Writing on August 3, 2011

I am LOVING this show. For all the wrong reasons.

I’m not a fan of the Idol franchise because it’s put in place a concrete, standardized checklist by which the general public believes singers should be judged. The idea, alone, that a vocalist should display versatility within a range of genres disqualifies the Billie Holidays and Neil Youngs of the world.

Before Idol, artists signed to labels existed in a reality parallel—but separate from—the rest of the world. Someone who ‘knew something about music’ had given the stamp of approval, pulled all the levers, and forevermore the glossy finish of album jackets and posters would seal that artist away, just out of fans’ reach. Talent was curated primarily by savvy executives like Clive Davis and Ahmet Ertegun, who certainly had a basic checklist for their signings (‘Can Sing,’ ‘Has A Look,’ ‘Has Presence Live.’) But, with a similar latitude that radio DJs had decades ago, one tastemaker’s gut instinct could play a large part in an artist’s destiny.

Today, with profits plunging and monster record labels merging to survive, indie labels have risen again to service niche markets while the majors pump out increasingly formulaic product. Those executives simply cannot afford to experiment, so clunky corporate procedure is de rigueur. I’m loving Bravo’s new reality series Platinum Hit because, perhaps for the first time, the curtain has been pulled back…the average music fan can get a relatively true-to-life view of the working parts inside the LA machine.

Appropriately, fallen singer-songwriter Jewel hosts. Her mis-step in 2003 with dance-pop single Intuition alienated her audience after her earthy image had been solidified with five ubiquitous alt-country radio singles. (We certainly saw under the hood of the industry for a moment there.)

The show is a competition in which 12 songwriters get thrown in rooms in various combinations to come up with hit songs…usually with a specific topic or genre, and sometimes for a specific artist. They work against the clock to deliver material to a panel of executives who then analyze the structure, melody, lyrics and chord changes to measure market potential.

This is exactly what goes on in Los Angeles.

I’m into this show because the corporate standardization of songwriting is in plain view. Heavyweight-songwriter-turned-reality-TV-judge Kara DioGuardi lobs constructive advice at the contestants, guiding them on how to get a green light from executives. Label-executive-turned-reality-TV-judge Keith Naftaly’s feedback often hinges on how well the song hits a market demographic. When in Episode 9 he told contestant Scotty Granger that he believes the lyrical content of his dance song is a little deep for high school kids, my eyes nearly rolled out of my head.

This is the type of ‘dumb-it-down’ thinking that permeates the industry. Scotty’s song was barely ‘deep’—in its narrative, we find out there’s just one day left on earth and everyone’s decided to dance all night. A bit dark, maybe, but hardly deep, and quite appropriate for the angst high school kids feel. Maybe this is why Britney Spears’ conceptually identical single ‘Until The World Ends,’ tore up the charts recently.

Regardless, kids, like anyone else, sense when they’re being talked down to, and this usually results in them finding a counter-culture that reflects their feelings more honestly. I remember a DJ friend pointing out to me that in the early 80s MTV was the only source for music videos, so all demographics were exposed to everything from Kate Bush to Run DMC. No one suffered from it. To the contrary, I believe it was a time of rich musical cross-pollination.

The last few episodes of Platinum Hit have gone slightly off the rails in the sense that contestants have clearly been eliminated not based on the quality of their songwriting but rather in order to maintain dramatic tension between characters: this still has to be entertaining TV. Nowhere was it more blatantly obvious than in shots of Granger’s own disbelief at having his song—which he had just described as unsuccessful—come in first at the end of an episode.

Artificially-imposed narrative aside, Platinum Hit is an interesting first glimpse into the world of beatmakers and topliners. The role of melodies, titles, song concepts, and chord changes is contextualized within the construction of a successful artist’s facade, giving some much-needed perspective on all that’s behind the front end of hit music.

The final episode of Season 1 airs this Friday August 5th.

Pop Smarts: Robyn

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Labels, Production, Writing on November 4, 2010

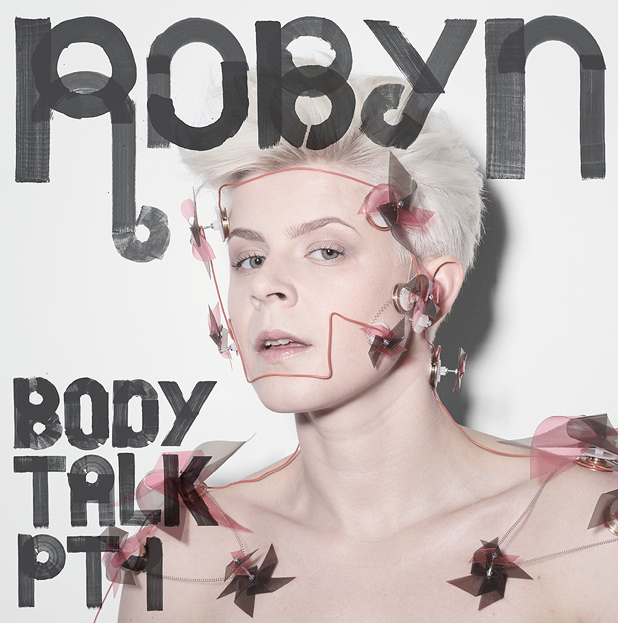

In 1997, RCA Sweden and legendary writer-producer Max Martin unleashed cute 18-year old popster Robyn on the world, sending flares up international charts with the R&B-tinged ‘(Do You Know) What It Takes’ and ‘Show Me Love’. The rest of the world was left to wonder once again how—from Abba to Roxette and The Cardigans—many a Swede has been able to tap in effortlessly to the North American pop sensibility. Further, she was a nordic girl with a measure of genuine soul in her voice. After a few more minor hits in Europe, Robyn disappeared from the world stage as quickly as she had arrived.

Fast forward a decade.

Word of mouth began rippling through the English-speaking world: undefeated by her major-label crash-and-burn, she’d quietly and intelligently risen from the flames. Taking the reigns both creatively and businesswise, she’d honed her songwriting craft with some hot producers and tested a new electro-pop direction locally with singles like ‘Dream On’. After necessary alterations, a deftly conceived full-length album—titled, simply, Robyn—followed on her newly christened Konichiwa Records. (The album also kicked off with the braggadocio rap ‘Konichiwa, Bitches’ — it’s Japanese slang for ‘Good Day’.)

A further revised version of the album arrived internationally and was supported with exhaustive touring. In concert she gives 110%, with heaps of cover songs along with her extensive canon of self-penned work. Her choice of covers shows a wide appreciation of other artists’ work: ‘Buffalo Stance’ by Neneh Cherry, ‘Try Sleeping With A Broken Heart’ by Alicia Keys and ‘Hyperballad’ by Bjork. Why all the YouTube links in this post? Because each one is worth it.

What’s special here is not that she’s come with great material, or that she put in the grunt work to rebuild the value of her brand from the ground up. It’s that she has the rare gift of self-awareness as an artist; the intelligence with which she’s packaged and marketed herself.

This year was the best example of it yet. After a couple years of radio silence, late 2009’s stunning collaboration with Röyksopp, ‘The Girl And The Robot’, primed us for a well conceived three-part ambush in 2010. Rather than releasing an album, she presented three shorter EPs. Distilled, the contents of Body Talk, Parts 1-3 would make a solid longplay album. But in an era when digitally downloaded music makes the number of songs on a release irrelevant, by conceiving a flexible new model like this she’s found a way to keep the excitement going all year long. Installments arrived in June and September. The final disc is slated for November 22.

Musically, the Robyn formula is smart. By giving us 1 part emotionally-level dance fun (‘Handle Me’, ‘Dancehall Queen’, ‘We Dance To The Beat’) and 1 part pseudo-gangsta attitude (‘Curriculum Vitae’, ‘Don’t Fucking Tell Me What To Do’, ‘Fembot’) upfront, we’re ready to go the distance with her as her heart bleeds through the remaining third of the material. And this is the material that really sticks: ‘With Every Heartbeat‘, ‘Be Mine‘, ‘Dancing On My Own’, ‘Hang With Me’, ‘Indestructible’.

Cleverly, the first two EPs also contained acoustic ‘preview’ versions of the lead-off single planned for the next EP, guaranteeing a boost of familiarity when the single versions of ‘Hang With Me’ and ‘Indestructible’ arrived with a Giorgio Moroder-esque thud.

What’s also striking is that Robyn, the artist and the businesslady, seems to have captured a demographic few else realized was there for the taking: the 30-something ex-raver that still craves rap and club music but wants something personal, melodic…clever.

The Creative-Commercial Cycle: How Pop Eats Itself

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Labels, Management, Production, Radio, Writing on August 19, 2010

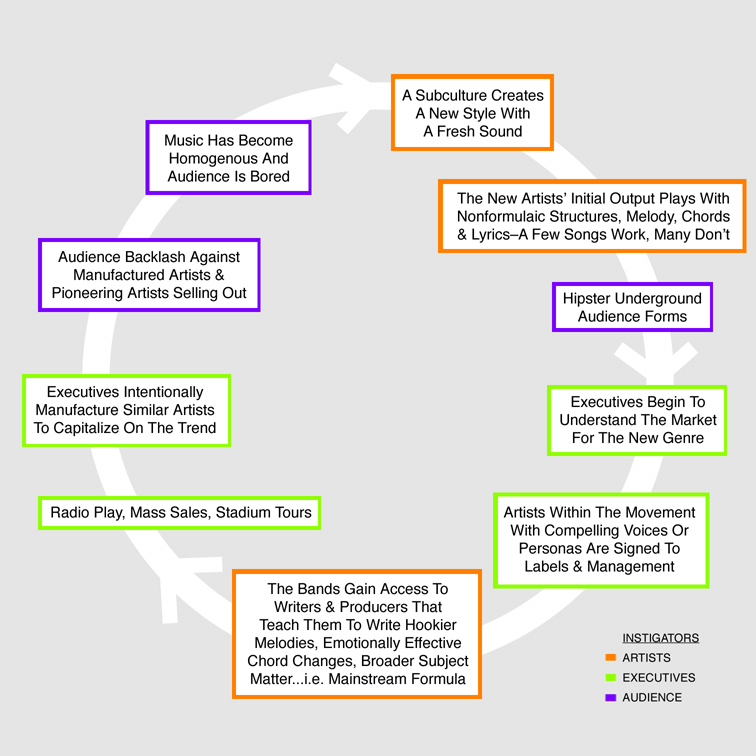

If it’s agreed that the following creative-commercial cycle occurs continuously in popular music…

…then there are a couple of things I find interesting. Namely, the process by which naturally compelling artists learn to create music with mass appeal, and the fact that this cycle seems to be speeding up as the executives get quicker at identifying and exploiting new trends.

For an example of the cycle, we can look at U2’s output. In the early 80s they had underground ‘alternative rock’ cool factor. The songs on their first two albums Boy and October were somewhat freeform. Melodies were cockeyed and noncommittal, lyrics never too direct. Bono’s voice and Edge’s guitar sound, together, supplied compelling personality. Steve Lillywhite’s production captured the band’s raw electricity without stylizing it.

War and The Unforgettable Fire followed, with ‘Sunday Bloody Sunday,’ ‘New Year’s Day’ and ‘Pride (In The Name Of Love)’ showing the first signs of a desire to write for radio. However, an inspired change in personnel brought a new depth to the sound of that fourth album: ambient visionary Brian Eno and roots musician Daniel Lanois were brought in to produce.

Not surprisingly, the subsequent writing on The Joshua Tree was significantly distilled. The straight-ahead stock chord changes and emotive melody of ‘With Or Without You’ as well as the clear, sweeping subject matter of ‘I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For’ and ‘Where The Streets Have No Name’ brought a mainstream audience to them as if by magnetic pull. If Eno and Lanois hadn’t purposely educated the band about mainstream pop writing, some form of growth-through-osmosis had happened as they opened up their creative circle.

Here’s a wordy section from ‘Drowning Man’ on War, followed by the confidence of the continuously building ‘With Or Without You’.

Since the watershed success of that album and the Rattle & Hum stadium tour–amid their core audience’s protests that the band had sold out–U2 has ridden out the last 20 years in various states of expectation-busting experimentation (Zooropa, The Passengers’ Original Soundtracks project) and pop duty fulfillment (All That You Can’t Leave Behind).

Bjork–who, incidentally, at first used her voice much like Bono had in the early 80s–first helmed Icelandic band Kukl, followed by The Sugarcubes. Her childlike voice and persona showed commercial promise amidst the disarray of the bands’ post-punk art-rock.

Teaming up with respected electronic producer Nellee Hooper, she emerged as a solo artist in 1993 with Debut, securing her place in pop history. The follow-up album was Post. ‘It’s Oh So Quiet,’ the big band single America loved to hate, was as straightforward as she would ever get before making her way back into ever-deeper experimental waters.

Compare the atonal rant from ‘Copy Thy Neighbour’ by Kukl with the soaring melody on the chorus of ‘Hyperballad’.

10,000 Maniacs is an interesting case that I made an effort to crack recently. I always had a like-hate relationship (as opposed to love-hate) with their In My Tribe, Blind Man’s Zoo and Our Time In Eden albums because I never quite understood how a band could sabotage moments of melodic virtuosity with such poorly considered arrangements. Or how such a compelling voice–meaning Natalie Merchant’s vocal instrument as well as the interesting angles she took on the songs’ subject matter–could be ruined by an equal helping of preachy condescension. As well, even after a string of five pop singles (‘Like The Weather,’ ‘What’s The Matter Here,’ ‘Trouble Me,’ ‘These Are Days’ and ‘Candy Everybody Wants,’) the band seemed to retain ‘alternative’ cred. Surely it couldn’t just have been based on their name.

A listen through their early recordings, reissued later on Hope Chest and The Wishing Chair, explained much. Like early U2 and Kukl, these songs are meandering stabs at writing, with hookless melodies, wordy, unclear lyrics and unremarkable chord changes. Also like Bono and Bjork, Merchant’s singular personality came through in her voice and the way she used it. 10,000 Maniacs guitarist Rob Buck, too, had an original style. Perhaps not as iconoclastic as Edge’s, but enough to show promise to a record company like Elektra. The band’s ‘alternative’ roots show in these recordings: in addition to the beginnings of their brand of quirky rock, we’re taken through painful world music experiments in Soca, Zouk and Dub Reggae.

‘Death Of Manolete’ from Hope Chest demonstrates the freedom of their wide-open creativity while the exquisite ‘Dust Bowl’ from Blind Man’s Zoo shows us the focus that took hold by the band’s second album with major label producer Peter Asher.

And so we have the artists, feeling around for something new to chew on, and the executives, racing to learn how to capitalize on a movement, a sound, an idea, a persona. They can’t exist without each other, so I don’t mean to imply that executives are the Cruella DeVilles of the world. But the crops need time to grow before the combine comes along to harvest. And in the age of the internet, traces of new artistic energy are identified and absorbed into the machine with breakneck acceleration.

One such ‘absorption cycle’ that makes me shudder is what occurred somewhere between 1995 and 2008, when Jill Sobule and Katy Perry each released a song called ‘I Kissed A Girl.’ Sobule’s song felt like the honest confession of a woman testing the fluidity of her sexuality. Perry’s felt like a market-researched ‘girls gone wild’ capitalization on straight mens’ fascination with girl-on-girl action. The sincere feminist perspective of artists like Sobule through the early 90s was officially absorbed into the machine when Simon Fuller auditioned British Barbie dolls for the Spice Girls. What was their mantra? ‘Girl Power’? Fast forward a decade, and it’s as though the feminist consciousness of the early 90s never existed. Lillith Fair sales are slipping this summer while the promo machine runs full-tilt for Katy Perry, who’s selling an updated Betty Page wet dream. Well, straight men still pull the budgetary levers at the major labels.

I was never fond of the smugly-named British band ‘Pop Will Eat Itself.’ As this creative-commercial cycle accelerates, however, I’m beginning to wonder if they were onto something. Adding momentum to this cycle is the fact that music went post-modern about 20 years ago. That is, sampling signified the gradual decline of truly new forms of pop music in favour of mixing original combinations of retro styles. If artists’ formulas weren’t made of old ingredients, it would be that much harder for executives to hack the recipe.

The ‘no rules’ artist to watch at this moment is Janelle Monae. She’s 24, she’s thoroughly disregarding anything that might be put on her as a female or a person of colour (in her own words: ‘I don’t have to do anything by default’), she’s got a big budget and she’s interesting. And–oh yes–she can sing. She can perform.

Andre 3000 and Big Boi of Outkast began working with her years back, and P. Diddy, of all people, has diverged from pop formula long enough to sign her and give her the kind of backing true artists only dream of in 2010.

Her trip is highly conceptual. Through a four-part suite, she’s reportedly telling the story of a robot named Cindi Mayweather who orchestrates an uprising in Metropolis. Her lyrics are so cryptic, however, that this storyline is barely apparent in the songs. At this early stage her output is coming across as a whole lot of disjointed concept, borrowed from many sources. If Fritz Lang doesn’t turn over in his grave at her shameless appropriation of his story, other visionaries like James Brown might. Virtually every song ends up a pastiche of the styles of several decades over the last century.

Melodically, the material is somewhat flat, the most memorable hooks lifted from elsewhere. Near the beginning of ‘Many Moons,’ a single from 2008’s Metropolis: The Chase Suite, she blatantly bites a riff from the Sesame Street pinball song we all know. After escaping the distraction of the very high budget of the ‘Many Moons’ video, it struck me that the most memorable moment of the song itself was that riff.

Selections from the new album, The ArchAndroid, include: ‘Cold War,’ its arresting single-shot video summoning the moment Sinead O’Connor shed a single tear for the camera in ‘Nothing Compares 2 U’; ‘Tightrope,’ with its main ‘on the scene’ hook lifted from ‘Sex Machine,’ (something she appeared to cop to as she donned a James Brown cape while performing it on David Letterman); ‘Sir Greendown,’ something like Shirley Bassey singing a version of ‘Moon River’; and ‘Make The Bus,’ like an outtake from David Bowie’s 70s trilogy produced by Brian Eno.

Another album track, ‘Locked Inside,’ feels good because it’s written over the chords of Stevie Wonder’s ‘Golden Lady’. It’s all crammed in there, cryptic and disorganized, from cabaret to hot jazz horns and 80s hip hop. And though it’s the work of an artist getting her bearings, both overdoing the concept and underdoing the original substance, she does appear to have the potential to change the game.

In order to keep that high budget record deal so she can mature creatively, it’s important that she have a bonafide hit sometime soon. And for that to happen the songs may have to fit into a framework that people understand a little more readily. There’s the catch-22: before the artist can ignore creative boundaries and lead the way, it seems she must first learn to simplify her writing. In days gone by labels could allow an artist several albums to reach a commercial stride. These days, it’s possible that other executives may be able to pinpoint what’s special about Monae early on and manufacture other acts that are capable of overtaking her. Hurry, Janelle, hurry and grow your garden!

Pressed Up Against The Glass: Visualizing And Discussing Sound

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Engineering, Mixing, Production on August 11, 2010

In 1966, during the recording of ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ for the Beatles’ Revolver album, John Lennon came up with a request phrased in the language of an artist: ‘I want my voice to sound as though I’m a Lama singing from a hilltop in Tibet’.

Producer George Martin had to interpret this request and come up with a concrete plan of action, which he then had to describe in technical terms to the recording engineer, Geoff Emerick, and the other assistants working under him.

Martin’s plan, documented in BBC’s interviews with George Martin on The Record Producers, was to play back the vocal track through a spinning Leslie speaker inside a Hammond organ and record that. I don’t know if the resulting warbly sound was exactly what Lennon had heard in his mind, but he was delighted with the freshness of the effect.

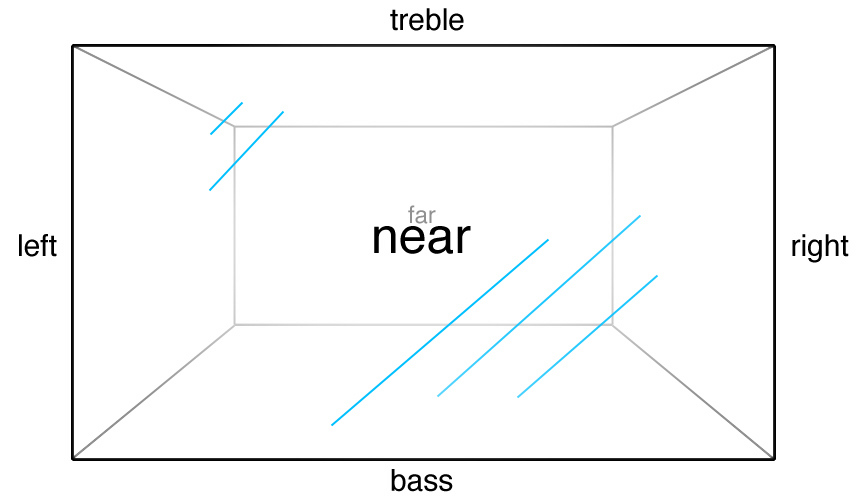

One of the greatest challenges producers face is coming up with the right language in discussions with artists and engineers. We’re all supposed to be sculpting the same thing. Mixing, for example, involves deciding on the placement of each instrument in a song – from its relative volume and clarity to its spatial positioning in the stereo field. Since we all interpret and describe sound differently, how do we take the seed of an idea born in one person’s esoteric imaginings and explain it clearly to a team?

The right metaphor helps.

A friend with musical leanings (and great skills in metaphor) once told me he likes to feel that he can walk into a recording and move around, visiting each instrument at will. He earmarked Steely Dan’s 1977 offering Aja as a good example of a sonically spacious album.

This idea of being able to ‘walk into’ a mix resonated with me, because I’ve always had a similar visualization of sound: I imagine the song is contained in a big glass box immediately in front of me. Sometimes I describe this model to the people I’m working with so we have a language for discussing our mix decisions.

In this box, a sound can be anywhere, left to right, in the stereo spectrum. It can be low or high, like the bass of a kick drum or the treble of a cymbal. It can be far away because it’s quiet and soaked in reverb (that residual echo of a bathroom or church), or it can be near because it’s loud and dry (just the direct sound with no reverb).

Trends in mix aesthetics come and go, and most of them are set in motion by an advance in technology. In the 60s drums were fed through analog compressors that tended to add a pleasing distortion, and big boxy reverbs were thrown on vocals using a huge room called an echo chamber. In the 70s 24-track recording became a reality and elements could be separated and controlled, making lush stereo arrangements possible. Digital reverb boxes came of age in the 80s, and reverb was applied liberally to snare drums and vocals.

Today the trend is for both of those elements to be almost completely dry. And recordings are significantly louder these days because with new digital compression plug-ins we can make each element much louder than we ever could in analog.

However when this is the case, as a listener I get the sense that the sound is aggressively being pushed out toward me–and pressed up against the glass–rather than inviting me in to explore. In fact I don’t like to be aware that there is a piece of glass between me and the music, but the more compression is used on the sounds in a mix to unnaturally increase their volume, the more obvious it becomes that the sound is hitting a wall, a limit. (Compression is explained beautifully in this two-minute video on the loudness war.)

This loudness war created a connundrum for radio stations that play both old and new music. Because their broadcast machines are calibrated for the loudness of newer material, older music sounded weak in caparison. That is why, a few years back, many major labels began remastering older music at higher levels in an effort to keep their catalogs in rotation–and to sell the same albums all over again to hardcore fans. Even if this meant the music sounded one-dimensional.

While striving to satisfy radio stations’ technical expectations, I look for ways to limit my participation in this ‘loudness war’ because aggressively mixed music tends to induce listener fatigue quickly. I want people to be able to put the records I produce on repeat! I listen to a lot of indie rock these days because those producers seem to have learned the subtleties of the new technology and found ways to make things impactful without flattening them against the glass in an obvious way.

My hope is that an upcoming technological breakthrough will steer us back toward utilizing the sonic depth we once valued. Most of the music I go back to exists casually in its space, enticing the listener in rather than forcing itself on them.

The Fate Of The 808

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Production, Remixing on August 3, 2010

The machine has been co-opted countless times to lend street cred to artist branding: early 90s UK techno act christened themselves 808 State; Kanye West dropped it in the title of his disc 808s & Heartbreak. And it’s regularly referred to by name in tracks like–wait for it–’808′ by Blaque. By now, the machine is more famous than some of the artists that use it. When Blaque sings ’cause I’ll be going boom like an 808,’ or Will.I.Am chants ‘we got the beat, that 808′ on the Black Eyed Peas’ ‘Boom Boom Pow’, we know they’re talking about the SUV-shaking kick of the world’s most celebrated drum machine, the Roland TR-808.

Legend has it that, in 1981, fledgling New York producer Arthur Baker travelled out to Jersey to buy a used 808. Roland had been manufacturing the unit for a couple of years, but like many new boxes, years can pass before someone stumbles upon a way to bring the art out of the technology. Baker brought the machine home and, reportedly, not knowing how to program it yet, he used a beat left in its memory by the previous owner as the basis of seminal rap track ‘Planet Rock’ by Afrika Bambaataa & Soulsonic Force, thus lifting the 808 from a potential fate of being a cheap novelty item stacked on pawn shop shelves for eternity. And that is how the disillusioned previous owner of that 808 turned out to be the nameless, faceless originator of that foundational ‘freestyle’ rap beat.

As the 80s progressed simple 808 beats began appearing on R&B jams by monster artists. After a short lull the machine had a strong resurgence in the early 90s, newly realized, in the stuttering double-time swing of ‘miami bass’ and ‘booty’ tracks. Post- millennium, its status as a classic has regularly been reinforced with new rap trends like Plies’ Southern post-booty beats and most recently in the sparse, ultra-high impact production sound of Kanye West and Drake.

Here are the basic, untweaked sounds of an 808.

The low, long tone of the kick drum is what most people recognize first. The clap, snare and cymbal sounds have come to feel like the sleek natural compliment to that low end, and the ‘cowbell’ sound, which bears little sonic resemblance to a cowbell at all, is really some kind of synthesized fifth chord.

Some 808 beats over the last 3 decades: the original freestyle beat of ‘Planet Rock’ by Afrika Bambaataa and Soulsonic Force (1982); straight ahead R&B jams ‘Sexual Healing’ by Marvin Gaye (1982) and ‘Who’s Zoomin’ Who’ by Aretha Franklin (1985); the syncopated miami bass beat on Inoj’s cover of Cyndi Lauper’s ‘Time After Time’ (1998) which incorporates a snare sample from another machine; Southern rapper Plies’ ‘Plenty Money’ (2008); the sparse 808 kick intro ‘Heartless’ by Kanye West (2008); ‘Successful’ by Drake ft. Trey Songz (2009).

In the early 80s Roland made a complete line of something-oh-something units. The 303 was a bass sequencer, initially relegated to the accompaniment of one-man polka bands and the like until it found a perfect home within the rhythms of late-80s acid house and mid-90s techno.

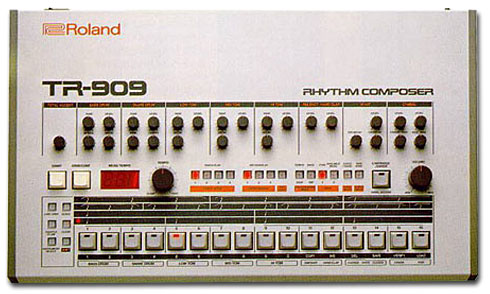

The 909 drum machine also sat, semi-used, until disco re-emerged…re-branded as ‘house’ in the late 80s: the 909 is to House as the 808 is to R&B and Hip Hop. The machine’s solid, pointed kick drum, crisp high hats and full-bodied clap, used together, ushered in the meditative swing of house music. In particular, rolling the 909’s snare in a multitude of syncopated patterns became the thing to do.

The 909 in action: pre-house snare rolls and echoey clap patterns on ‘Pump Up The Volume’ by M.A.R.R.S. (1987); syncopated snare on ‘E.S.P.’ by Deee-Lite (1990); Shep Pettibone’s snare-happy house mixes of ‘Escapade’ by Janet Jackson, ‘Express Yourself’ and ‘Vogue’ by Madonna (1989-90); MK’s 909-heavy remixes of ‘Movin’ On Up’ by M People, ‘Can You Forgive Her’ by the Pet Shop Boys and ‘Heart Of Glass’ by Blondie (1993-95); and a 909-only beat on the Musk Men bootleg of ‘I Never Thought I’d See The Day’ by Sade (1995).

There are a few other early drum machines worth noting for the impact they had on music as we know it.

Roger Linn created the Linn LM-1 in 1980, and it quickly became the go-to machine for pop production in the U.S. and U.K.

The LinnDrum and Linn 9000 models followed, adding a few more sounds to the initial palette.

Countless instantly recognizable beats were programmed on these machines including ‘The Look Of Love’ by ABC, ‘Don’t You Want Me’ by the Human League, ‘Love Is A Battlefield’ by Pat Benatar, ‘Shock The Monkey’ by Peter Gabriel, ‘Dress You Up’ by Madonna, ‘Wanna Be Starting Something’ by Michael Jackson, ‘Mama’ by Genesis and ‘Everything She Wants’ by Wham.

A friend used to joke that Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis must have had a climate-controlled room with a sleek black box the size of a tank to produce sounds as big and clunky as they used on Janet Jackson’s ‘Control’ and ‘Rhythm Nation’ albums. Evidently, however, the production team often used Linn machines drenched in gated reverb for Jackson’s signature sound.

Prince crafted virtually everything he produced in the 80s with these machines as well as two others, defining a funk sound we all know.

The raw sounds on Sequential Circuits’ Drumtraks sounded like this:

Oberheim’s OB-DX sounded like this:

With a little manipulation (re-pitching the sounds and adding various effects to them) he was able to create a fresh basis for each new song while defining his production sound. In particular, he seemed to use the Drumtraks clap a different way on virtually every track.

Some samples of Prince’s production from ‘Nasty Girl’ by Vanity 6, through a range of his solo work over the decade including ‘Let’s Pretend We’re Married,’ ‘Little Red Corvette,’ ‘Let’s Go Crazy,’ When Doves Cry,’ ‘The Beautiful Ones,’ ‘Raspberry Beret’ and ‘Kiss’:

No tour through notable 80s drum machines would be complete without mentioning Simmons drums. These were actual physical drum kits produced in varying incarnations between 1980 and 1990 with hexagonal electronic pads that triggered a synthesizer box.

Some individual sounds.

The instantly recognizable white noise fakeness shows up sporadically on all kinds of prog rock, new wave and funk. Some examples are the intro to ‘Somebody Told Me’ by the Eurythmics, the whole drum groove of ‘She Blinded Me With Science’ by Thomas Dolby, the accents in the break of ‘Mr. Roboto’ by Styx, and the snare on ‘Word Up’ by Cameo.

Sade As Wounded Warrior

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Production, Singing, Writing on March 18, 2010

It hurts to write a single sour word about Sade. Being a lover of music in many disparate genres it’s difficult to play favourites, but over time I’ve come to realize that Sade does hold the Best Artist spot for me. Against much more obvious competition, ‘The Sweetest Taboo’ has unexpectedly landed as my favourite song, and 1985’s ‘Promise’ would be the album I’d take to a desert island.

She, the woman, and they, the band, have come to represent high taste and integrity in music. They’ve built a trust in their fans that the product will be filtered and distilled before it reaches us: there is no chance for cheapness to get through. Much of their music has been slow-burn: it takes time for such subtle grooves and sparse melodies to get under the skin. The last few albums of new material, each released in a different decade, have been increasingly moody and subtle–increasingly less immediate, but with a satisfying payoff after repeated listens. Although Sade has never professed to be a vocal athlete, the band is always on point and the ambiance she brings with her cool presence makes them one of the few live acts that I cannot miss. With a 10-year gap since their last studio album, curiosity and expectations were high. I put off writing about the band’s new album, ‘Soldier Of Love’ for several weeks in order to digest it and give it a fair shot.

Sade has allowed unprecedented media access this time around, and in the course of it much has been made about her previous insistence on privacy. She shook hands around the room at the NYC album listening party, performed the single on every major talk show, and satirized herself in a guest appearance on the Wanda Sykes show. Articles like this one in the London Times have combined historical context with personally revealing interviews. Soundbites from a recorded interview were made available here. A short film surfaced discussing the making of the album, and then another appeared about the making of the first video.

Sales have been excellent, indicating that the band’s following is still a faithful army in this day where the pirate download has become standard. The album went straight to number one on the Billboard chart and held strong, proving strong radio action is not required to sell such a trusted band these days.

So is the new disc good? It is. I’m afraid to say however that it’s not phenomenal, and certainly not groundbreaking or revelatory.

Let’s do a little bit of history. The band began as a live jazz outfit. 1984’s ‘Diamond Life’ was made up largely of songs they’d already been playing around London, including most notably their throwback anthem ‘Smooth Operator’. Robin Millar produced, beautifully packaging their organic jazz café sound, a sound which spun out into a movement in 80s England with bands like The Style Council and Simply Red filling out the genre. In the first few videos a narrative was built around Sade as a jazz-club diva mixed up in a gangster plot. Album tracks like ‘Frankie’s First Affair’ and ‘Sally’ brought seedy, urban characters to life. ‘Hang On To Your Love’ and ‘Your Love Is King’ were classic, universal love songs.

The band’s follow-up, ‘Promise,’ arrived just a year later with the melodically sweeping first single ‘Is It A Crime’ continuing the torch song tradition. ‘The Sweetest Taboo’ was a light singsong with darker lyrical undertones, built around a highly original syncopated kick-and-rimshot pattern not heard in music before or since. ‘You’re Not The Man,’ another stunning jazz ballad, only appeared on vinyl as the b-side of ‘Taboo’; it was thankfully included on the non-vinyl versions of the album. ‘Maureen’ and ‘Tar Baby’ were again character pieces, but this time Sade took a page from her personal life, singing about her best friend and her grandmother. The first hint of sequenced electronics appeared on ‘Never As Good As The First Time’ and a quick scan of the album credits reveals that this was one of the band’s first forays into sharing production duties with Robin Millar. It was the first sign of a departure they were about to take.

While it’s easy to see that most of their early material was built around elaborate, classic melody, ‘Never As Good’ is a groove-based song. Sitting somewhat conspicuously next to fully organic songs on the album, the drum machine loop and percolating synths settle us into a hypnotic groove, and the verse vocal weaves itself rhythmically into that groove, the melody flipping between two neighbouring notes. It is a different way to write music: it comes from the opposite angle, building on a rhythmic foundation rather than a melodic one.

There was a 3-year break. When the band returned with ‘Stronger Than Pride’ in 1988, they had taken over production duties from Millar, who, tragically, had gone blind from an inherited retinal disease during the recording of ‘Promise’. The jazz influence had faded, echoed only on the horn arrangement in ‘Clean Heart’. It was replaced by the band’s own unique R&B sensibility. Most importantly, they were favouring this new approach of writing over programmed loops, and here I believe is where Sade’s melodic and lyrical approach began to change from the lighter character-based storytelling of ‘Sally’ and ‘Maureen’ to a longer, drawn-out process of feeling around for the singer’s own subconscious undercurrents. There seemed to be a belief that the lyrics needed more sombre depth to them, more of a message.

1992’s ‘Love Deluxe,’ and 2000’s ‘Lover’s Rock’ furthered this direction, forging original works over many different feels and grooves. Unlike the big jumps on the first two albums, melodies generally fluttered between a few neighbouring notes, except on the more commercially viable songs ultimately chosen as lead-off singles (‘No Ordinary Love’ and ‘By Your Side’ respectively).

And now ‘Soldier Of Love’.

Despite the band’s insistence that they work hard not to repeat themselves, for the first time I feel there is a degree of repetition going on here. The title track bites chord progressions from ‘No Ordinary Love’ and melodic bits from ‘Somebody Already Broke My Heart’. The bouncing tambourine in the drum groove on ‘The Moon And The Sky’ also recalls ‘No Ordinary Love’; the rhythm track on ‘Skin’ recycles that of ‘Cherish The Day’. After ‘The Sweetest Taboo’ and ‘The Sweetest Gift,’ the title ‘The Safest Place’ looked oddly familiar in the track listings. It is also the obligatory beat-free moment on the album–a tradition that began with ‘Fear’ on ‘Promise’ and carried through, one track per album, with ‘I Never Thought I’d See The Day,’ ‘Pearls,’ and ‘It’s Only Love That Gets You Through’. If they were putting out records every two years, these similarities wouldn’t matter so much. But considering we’ve just had the longest gap between releases, I would have loved to see the band forge new paths rather than rely on old habits.

Once stating that timelessness was one of the mandates of her writing, Sade’s first lapses in taste have now happened: the cheap reference to Kool Moe Dee’s ‘Wild Wild West’ on the ‘Soldier Of Love’ single, perhaps meant to show light irony; the reference to ‘Michael, back in the day’ layered with a simulated MJ holler behind it on ‘Skin,’ likely included to acknowledge the loss of a personal hero; and a few somewhat embarrassing moments in ‘Babyfather,’ beginning with ‘she liked his smile, she wanted more, the baby’s gonna have your eyes for sure.’ The idea of including Sade’s daughter Ila and bandmate Stuart Matthewman’s son Clay as a childrens’ chorus on ‘Babyfather’ points toward a lapse in judgment due to unchecked parental pride. It is unfortunately likely to be the second single because it is the only light storytelling moment on the record, and there’s not much else with an obvious radio hook.

Production- and writing-wise there are some developments on the disc. A blues influence–something we first heard in the band’s cover of ‘Please Send Me Someone To Love’ on 1994’s ‘Best Of Sade’ collection–has emerged more strongly here on ‘Long Hard Road’ and ‘Bring Me Home’ among others. The reggae influence of ‘Lover’s Rock’ has deepened in the form of dub basslines peppered through the album and some lush three-part harmonies reminiscent of The Wailers on the bridge of the ‘Soldier Of Love’ single, which also boasts the new sonic colours of army battery drumming, futuristic synth effects and one ferocious hip hop snare. I welcome back Stuart Matthewman’s saxophone lines after their absence on ‘Lover’s Rock’. Upon sitting with the record, ‘The Moon And The Sky’ seems as though it will be one of the songs that will deepen with time. ‘Morning Bird,’ while cryptic and mournful, is exquisite and feels like the gentler moments of the 1996 Sweetback album (the band’s side project without Sade). ‘In Another Time’ feels like lazy writing, full of melodic gaps, but lyrically it is special in the way it captures a mother-daughter advice session.

There is a sentiment of sombre fortitude or bitter resolve present throughout the album; a running theme of being a soldier (the title track) or warrior (the closing track). The rest of the songs tend to lament loss or to wearily offer encouragement. I’m not sure whether this darkness reflects where Sade is at personally, or whether she feels it is only worthwhile to document the heavier things inside her, because the writing itself also feels quite laboured to me. One of her gifts as a writer has been her ability to reach in and describe a feeling directly or metaphorically, yet without a trace of cliché…case in point: the phrase on ‘Be That Easy’ where she states both simply and profoundly ‘for I am a broken house, I’m holding on a broken bow’. However I believe she has become fixated on this one particular gift rather than using her complete palette: for a very long time the songs have not been melody driven and they have not included those narrative stories less related to her personal demons and philosophies.

In the ‘Making Of Soldier Of Love’ footage–the first time information has been let out about the band’s creative process–there is a lot of talk about the ‘struggle’ involved in the writing process. The band and Sade herself express, wearily, an exhaustive search that goes on in the writing of each song. She explains that she stays away from the studio for long stretches of years because it’s such a commitment to go in and make an album. She sighs with the heavy weight of her own expectations that the music be built on truths and constructed with love. She flips through a stack of papers several inches thick saying ‘look how many words, look, all of this, it’s one song,’ revealing that there are endless rounds of adding and chipping away at words in the search for the right ones.

She analogizes her process: ‘once I start working on a song I sort of feel I’m on a boat, and the boat knows which way it’s going…sometimes the boat will go off course and I have to fight to steer it back.’ Also, ‘the three minutes where the song really comes together in that moment where it sort of arrives from the ether or wherever, then the rest, a lot of the rest is working on maintaining the spirit that came to you from no will of your own, and that’s the difficult part…being loyal to the original vibration and spirit of feeling that came with that song.’ This struggle, I feel, is a process Sade has put on herself, and in my experience it’s what would produce the heaviness, the laboured feeling of the music. While this gradual syphoning of the subconscious–of connecting to the ether without staring it down directly–is not an uncommon approach and it is valuable for some songs, we also know from her earlier work that she’s capable of balancing out this heaviness by writing sweeping melodic stories off the cuff.

And this is really what I want to say about the new album: it may be that Sade now goes into the studio simply trying to initiate the purge she believes is expected of her. In that way I believe she’s gradually misconstrued, by small degrees, what her job as a musician is. At the other extreme we have artists that push the boundaries as far as possible with each new album to break out of the shell of what’s expected. I feel the best work happens somewhere in the middle, in a space when original ideas are allowed to flow naturally with little reaction to what’s worked before. And the best songs seem to come when the conscious mind vaguely teases the subconscious out, but it is not always helpful to approach the studio expecting drawn-out martyrdom. I want Sade to have fun writing the music she presents to us.

This Guy’s Crazy

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Writing on January 4, 2010

In general I’m far more interested in hearing a singer-songwriter deliver their own lyric than hearing a performer sing something that was penned for them by an assembly line writer. By definition, I think a singer who chronicles their own thoughts and feelings can deliver authentic human experience more directly than one who acts out lines crafted by another person. So I cherish the work of auteurs like Stevie Wonder and Joni Mitchell, and I’ll take Alanis Morissette over Britney Spears and Mary J. Blige over Whitney Houston.

I can certainly leave a tradesperson like Diane Warren, who for many years was LA’s go-to writer for romantic schlock like Toni Braxton’s ‘Unbreak My Heart’ and Celine Dion’s ‘Because You Loved Me’. Warren claims never to have been in love, and she hates dating. In a way, her inexperience with love does show in the almost camp, overshot grandiosity of her lyrics. And while overshot sentiment sells because it gets its point across quickly and clearly, I just have a fundamental issue with pinning my own romantic yearnings to somebody’s calculated product.

But there are exceptions to my ban. One is the Motown assembly line of the 60s, in which Holland-Dozier-Holland wrote the most significant portion of the material for an entire stable of artists in Detroit. My theory there is that the momentum of the label’s fresh, exciting sound and the writers’ melodic gifts attracted every aspiring singer in the city…and then the universality of the lyrics allowed the singers to throw themselves into performances convincingly, as though the songs were confessionals from their own lives…similar to an artist choosing to record a cover version of someone else’s song because it has tremendous personal significance for them.

Another exception is New York’s Brill Building, which fostered a competitive atmosphere for songwriters, peaking in output in the late 50s and early 60s with Burt Bacharach, Neil Diamond, Carole King, Neil Sedaka and Phil Spector all hanging around, pushing each other to be greater songsmiths. Again: an almost magical kind of momentum seems to have been present.

Those I would call auteurs appear to discover the chorus of a song organically from a personal feeling or event they’re describing. In contrast, assembly-line writing often involves first searching for one original, evocative central concept (ie ‘You Make Me Feel Like A Natural Woman’ came out of the Brill Building for Aretha Franklin) that will serve as the chorus, and then fashioning the rest of the song outward from that…creating verses and bridges that will set up and support the story, always bringing us back to the point the chorus makes. Slightly cheaper than working from an original central concept, an unused pop culture catch-phrase will suffice as the chorus (Motown’s writers gave ‘You Beat Me To The Punch’ to Mary Wells). Today much top 40 rap is based around nabbing the most up-to-the-minute catch-phrases and creating a cool/dirty/funny track around that (see ‘Superman That Hoe‘ a/k/a ‘Crank That’ by Soulja Boy).

A few weeks ago Island/Def Jam artist Jenna Andrews played me a rough cut of her upcoming debut album. A gorgeous production featuring her instantly recognizable voice upfront, much of it was penned by the industry’s fastest-climbing new writer Claude Kelly. And I need to tell you…this guy’s crazy. Jenna described his pen-and-paperless process to me: he toplines (writes lyrics and melodies over instrumental tracks) by getting into the vocal booth, turning down the lights, balling up on the floor and having the engineer play the track on repeat for a while. He locks in to who he’s writing for and finds the sentiment. Then he gets up and writes at the mic, no doubt influenced by the freestyle process of many rappers…but he also mimics the voice of the person he’s writing for. He goes back and forth within the song as necessary, changing and filling in lines, taking about two hours to put down an entire song complete with background vocals.

Claude’s still in his 20s and he’s already written hits in several styles, including ‘Circus’ for Britney Spears, ‘Party In The U.S.A.’ for Miley Cyrus and Adam Lambert’s ‘For Your Entertainment.’ He’s written extensively for Akon and Toni Braxton, and for Whitney Houston’s comeback album. To understand the way he embodies the singer he’s writing for, check out the excellent ‘I Hate Love,’ a demo he recorded for Toni Braxton. The song’s unique central concept is the idea that someone could come to hate being in love because each day spent away from your lover is exceedingly painful. This oddly dark sentiment is somehow appropriate for her persona and his delivery is full of Braxtonisms. A quick search of his name on YouTube reveals an array of leaked demos of unreleased songs for a range of artists…judging by the sound of his delivery, some of them would seem to be for Akon, Whitney Houston, and Trey Songz.

We have modern-day net leakage to thank for this type of insight into a fascinating writing process. I hate to throw the phrase ‘bonafide genius’ around, but let’s say Claude Kelly is a talent to watch. It would be even more interesting to hear a Claude Kelly solo record, giving him the opportunity to step into the role of auteur…and to sing as himself.