Archive for category DJing

Exclusive vs Inclusive Clubbing

Posted by Gavin Bradley in DJing on July 23, 2009

Have you ever noticed that there are two main kinds of clubbing experiences? Well there are…exclusive and inclusive. And from what I can tell they draw two different types of crowds for two different reasons.

Exclusive clubs rely on guest lists and dress codes to maintain that feeling of exclusivity. If you got in, you’ve met the club’s fabulousness quotient and you’ve been lifted above all that riffraff still waiting in line outside.

Studio 54 in late ’70s New York was the mother of all exclusive clubs. It was about decadent decor and lavish procession, seeing and being seen. Bianca Jagger rode in on a white horse once. It was the preferred club for celebrities to hold their parties at and any mortals lucky enough to get in would rub elbows with the stars and have stories to tell for the rest of their lives. The currency of the club was that rush of feeling like one of the chosen ones…and that could only happen because the rest of the world was excluded from the party.

While it would have been a sight to witness, I probably wouldn’t have actually had a good time at Studio 54 because in general I’m not into that exclusionary clubbing experience.

I like inclusive places where anyone can get in, wearing anything, without a guest list hookup. When you’ve got great music and no attitude, people come to dance. There’s an infectious happy energy created by diversity in a crowd. And you won’t find a lot of posers when people are truly there for the music.

In ’90s New York I had the pleasure of attending Body And Soul held at Club Vinyl. The legendary resident DJs were Francois K, Danny Krivit and Joe Claussell. The club was the after-after party to Saturday night…it began Sunday afternoon. No alcohol was served, just bottled water. Whatever the substances of choice were, usage was not overt. There really wasn’t even much of a light show. I just remember three stacks of speakers, a couple of stories high, facing a packed, sweaty, dark dancefloor. And every kind of person was there, absolutely going off to the music.

Late 80s warehouse parties and early 90s raves were inclusive events. Though the location was always mysterious, if you found the place you were welcomed to the party no matter who you were or what you looked like.

On the flipside, gay circuit parties in the late 90s were exclusive: only muscle marys with major disposable income need apply.

A great party that’s still going on in New York is an outdoor jam called the Soul Summit that takes place every Sunday through the summer in Brooklyn’s Fort Greene Park. It’s like an earthier, free outdoor version of Body And Soul. Diverse, positive and inclusive. These people are strictly about the music and they like it soulful and deep.

Toronto has its own outdoor sound system on summer Sundays called Promise. It’s free, the roster of guest DJs rotates, and you might hear anything from reggae to freestyle to funk to hardcore in one evening. It operates by word of mouth, moves around a bit but generally stays near Cherry Beach.

It’s full of hippies and ex-ravers, young couples with their dogs and kids, the odd soccer team…? Whoever hears the sound through the bushes arrives to find a happy and welcoming party by the water.

If you think about it, you can pretty much walk into any party and figure out in a few moments whether it’s an exclusive or inclusive environment. Usually if it’s exclusive I tend to walk back out.

Hard Cuts, Beat Mixing & Train Wrecking: The DJ As Performer

Posted by Gavin Bradley in DJing on May 21, 2009

It’s difficult for an audience in a club to know exactly what the DJ is manipulating at a given time and what’s already part of the track they’re playing. Too often I’ve heard someone on their way out of a club crying ‘the way that DJ remixed the new Britney was fiiierth!’ (or some variation) making it obvious that they believe DJs ‘remix’ songs on the spot, creating a new version of a song by laying an acapella over another track that they’re creating live. Nine times out of ten what’s happening is the DJ is simply playing a remix a producer slaved over in the studio for a few weeks…it’s just a remix that particular club-goer hadn’t heard before.

There are exceptions. Joe Claussell is a New York-based DJ who constantly manipulates the music he’s playing. He’ll often have a drum track looped while he twists a knob on his mixing desk in quick rhythmic stabs, teasing the crowd with chopped-up, filtered hints of a vocal track before bringing it in fully.

In Toronto, Deko-ze is a DJ I’ve watched keep four tracks running simultaneously, mixing and matching elements from all of them, looping a beat on a CD deck in front of him while reaching off the to side to nudge a record like a plate spinner sensing the need for a slight adjustment.

Some laptop DJs running Ableton Live are able to perform in a similar way because the software has the flexibility to loop a section of one track while the DJ chooses sections of other tracks to bring in, however the need to develop the physical skill of matching the speed of two tracks is eliminated because the software does it for them.

What the audience needs to understand is that a DJ spinning vinyl or CDs cannot separate individual parts of a track unless they’ve been supplied individually on a single or a bootleg. In other situations the best they can do is filter out the bass in a track to clear away some drums and expose the vocal a bit more, or filter out the treble to do the opposite. DJs that are acrobatic enough to have 2, 3 or 4 tracks spinning simultaneously are often layering drums on CD decks (they’re able load a perfectly looped section into memory), adding an acapella they obtained somewhere, and possibly adding musical elements from an instrumental mix of another track. It’s possible to go back and repeat a section of a vocal, or something relatively simple like that, but it’s difficult to apply rapid-fire effects to a vocal. Often you’re hearing something that’s on the acapella already, or the DJ has done some preparation of the track at home first.

What the great majority of DJs do is play one track after another, and the only time more than one element is being heard at the same time is while the DJ is fading from one track into the other, making use of the drums-only intros and outros tacked onto virtually every club track available today. Essentially, club tracks are designed like Lego blocks. The next one snaps onto the last one in most any configuration. It’s known as ‘Train Wrecking’ when a DJ messes up by letting two drum tracks get out of sync with each other while fading from one track to another…because, ostensibly, it sounds as messy as a train going off the tracks.

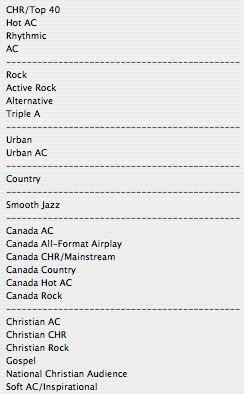

Club audiences have splintered into as many genres as house music has fractured into. And a DJ that only needs to play one genre, like dubstep or electro, doesn’t have to worry too much about the tracks they play being wildly different in tempo, rhythm or sonic range. Within this realm, the difference between a good DJ and a bad DJ is their taste in tracks, and their ability to read a crowd.

On the extreme side of DJ laziness is Israeli superstar DJ Offer Nissim, who is rumoured to put on a full-length CD created in the studio beforehand and pretend to mix all night from one track to another, collecting a $20k cheque at the end for showing up and ‘performing’!

In the early 90s, when turntables were the only sound source and DJs would begin a night with R&B and rap, progressing to house and eventually hard techno by the end of the night, the DJ had to work hard to learn what worked and what didn’t. Those turntables didn’t have as wide a pitch adjustment range as technology offers now, so beat-mixed music would have to change tempo incrementally over a few tracks.

Some all-but-lost creative mixing techniques include ‘braking’ (hitting the Stop button on the turntable to slow one track dead and then starting the next one, a technique used to start a set in a different tempo) and the ‘hard cut’ (where a DJ would surprise the crowd by cutting from one track directly into another). Hard cuts were sometimes necessary because tracks didn’t always begin with long drum intros…keyboard or acapella intros were acceptable on a 12″ version and this required the DJ to get a little creative.

One of my favourite creative mixes exists on a mixtape made by Toronto’s Patrick ‘D-Nice’ Hodge in 1992. It’s somewhere between a regular crossfade and a hard cut:

At 0:23 the piano riff that comes in is from the next record, ‘Back To Me’ by Ubiquity. This riff is in the same key as the previous record, and it works beautifully with the existing chord progression we’ve been listening to. At 0:31 he drops the first record entirely, as the beat comes in on the new record. The fact that he recognized these two records in his crate would work together in this way is one of those happy accidents that happen increasingly often the more attuned a DJ gets to his material. The second track coming in, by the way, is just slightly flat, because at that time in order to line up the tempo of two recordings, the original pitch of the recordings would slide around as necessary. That’s no longer an issue with CD decks and laptops.

I still don’t know what track Patrick was mixing out of here. If anyone can identify it, please hit me with an e-mail.

Continuing back in time to the mid-70s when DJs like Tom Moulton in New York discovered disco’s relentless ‘4-on-the-floor’ kick drum pattern, the concept of beat-matching two tracks while mixing from one to the other was born. It’s worth mentioning that at that time there were even greater physical challenges for the DJ. Most of these tracks were not recorded at a stable tempo, so the DJ was constantly adjusting the turntable to keep the beat aligned, especially if they were trying to keep two songs running together for more than a few seconds. DJ turntables with convenient pitch sliders and robust tonearms/needles hadn’t been developed yet and neither had 12″ singles with extended versions that had long drum breaks for mixing.

Moulton was reportedly the first DJ to make long versions of his favourite songs by editing them on reel to reel tape and bringing the machine to the club that night. Some of his re-edits were later released by the original labels. I also have it on good authority that at Studio 54, staples like ‘Come To Me’ by France Joli would be extended manually by the DJ by mixing back and forth between two copies of the same record. DJing was a highly physical act at the time, and within the technical limitations there was quite a bit of creativity going on.

Addiction: Fred Everything ft. Wayne Tennant – ‘Mercyless’

Posted by Gavin Bradley in DJing, Production on May 19, 2009

Wayne Tennant was the lead singer of Toronto funk band God Made Me Funky, then he moved to Montreal, started recording some solo work and spent some time playing Morocco and recording in the UK.

He’s done a collab with Montreal deep house producer Fred Everything for Fred’s album ‘Lost Together’ (Om Records). The track is called Mercyless…the single hit #2 this week on Traxsource…the only soulful house online store that matters. Tastemaker DJ/producer Osunlade also has it in his top ten right now.

Here’s a sampler of the mixes on the single. In order: the original LP mix, then the deeper Fred Everything & Olivier Desmet Remix, then the smooth AtJazz remix.

It’s a slow-burn. I liked it on first listen…I was addicted to it after a few. Wayne’s solo EP is coming out this summer.

Pan & Throw

Posted by Gavin Bradley in DJing, Mixing, Remixing, Singing on May 19, 2009

This blows my mind every time I listen to it:

What you’re listening for is a 16-bar section toward the end of ‘Luv Dancin’ by Underground Solution…circa 1991. Classic house music on the legendary Strictly Rhythm label. The main hook of the track is a female vocal sample from Loose Joints’ disco classic ‘Is It All Over My Face’. There is a version with a full female vocal as well. But there’s a male vocal snippet from the Better Days Remix of Carl Bean’s ‘I Was Born This Way’ weaved into the tapestry and in this part of the extended version the producer decides to riff on that sample for a minute before winding down and man it gets me every time.

It’s partly the sample itself. It’s got that gospel depth to it…he’s feeling that shit…and the way he ends his phrase, trailing down, to a gritty release…there’s tragedy there.

But there are also choices that the producer and/or mix engineer made: the sample pans left and right, sometimes it’s ‘dry’ (no effects), sometimes there’s a delay throw (certain syllables echo) and sometimes there’s a reverb throw (a big roomy sound on it). The patterns entrance me. So simple, yet so complex. So inspired, so not systematic. I could loop those 16 bars all day.