Archive for category Labels

Platinum Hit: Under The Hood Of The Music Industry

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Business, Creative, Labels, Publishing, Writing on August 3, 2011

I am LOVING this show. For all the wrong reasons.

I’m not a fan of the Idol franchise because it’s put in place a concrete, standardized checklist by which the general public believes singers should be judged. The idea, alone, that a vocalist should display versatility within a range of genres disqualifies the Billie Holidays and Neil Youngs of the world.

Before Idol, artists signed to labels existed in a reality parallel—but separate from—the rest of the world. Someone who ‘knew something about music’ had given the stamp of approval, pulled all the levers, and forevermore the glossy finish of album jackets and posters would seal that artist away, just out of fans’ reach. Talent was curated primarily by savvy executives like Clive Davis and Ahmet Ertegun, who certainly had a basic checklist for their signings (‘Can Sing,’ ‘Has A Look,’ ‘Has Presence Live.’) But, with a similar latitude that radio DJs had decades ago, one tastemaker’s gut instinct could play a large part in an artist’s destiny.

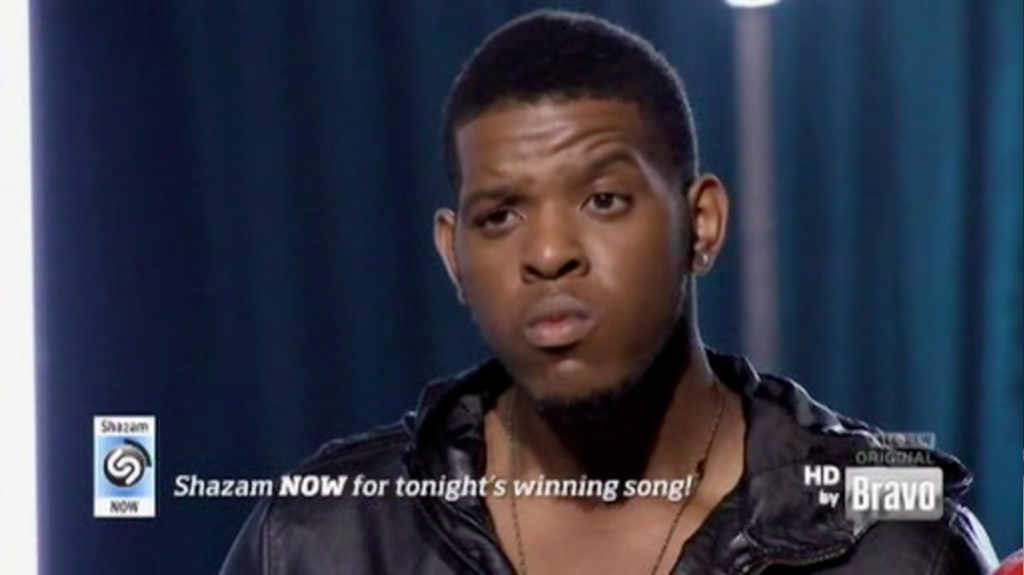

Today, with profits plunging and monster record labels merging to survive, indie labels have risen again to service niche markets while the majors pump out increasingly formulaic product. Those executives simply cannot afford to experiment, so clunky corporate procedure is de rigueur. I’m loving Bravo’s new reality series Platinum Hit because, perhaps for the first time, the curtain has been pulled back…the average music fan can get a relatively true-to-life view of the working parts inside the LA machine.

Appropriately, fallen singer-songwriter Jewel hosts. Her mis-step in 2003 with dance-pop single Intuition alienated her audience after her earthy image had been solidified with five ubiquitous alt-country radio singles. (We certainly saw under the hood of the industry for a moment there.)

The show is a competition in which 12 songwriters get thrown in rooms in various combinations to come up with hit songs…usually with a specific topic or genre, and sometimes for a specific artist. They work against the clock to deliver material to a panel of executives who then analyze the structure, melody, lyrics and chord changes to measure market potential.

This is exactly what goes on in Los Angeles.

I’m into this show because the corporate standardization of songwriting is in plain view. Heavyweight-songwriter-turned-reality-TV-judge Kara DioGuardi lobs constructive advice at the contestants, guiding them on how to get a green light from executives. Label-executive-turned-reality-TV-judge Keith Naftaly’s feedback often hinges on how well the song hits a market demographic. When in Episode 9 he told contestant Scotty Granger that he believes the lyrical content of his dance song is a little deep for high school kids, my eyes nearly rolled out of my head.

This is the type of ‘dumb-it-down’ thinking that permeates the industry. Scotty’s song was barely ‘deep’—in its narrative, we find out there’s just one day left on earth and everyone’s decided to dance all night. A bit dark, maybe, but hardly deep, and quite appropriate for the angst high school kids feel. Maybe this is why Britney Spears’ conceptually identical single ‘Until The World Ends,’ tore up the charts recently.

Regardless, kids, like anyone else, sense when they’re being talked down to, and this usually results in them finding a counter-culture that reflects their feelings more honestly. I remember a DJ friend pointing out to me that in the early 80s MTV was the only source for music videos, so all demographics were exposed to everything from Kate Bush to Run DMC. No one suffered from it. To the contrary, I believe it was a time of rich musical cross-pollination.

The last few episodes of Platinum Hit have gone slightly off the rails in the sense that contestants have clearly been eliminated not based on the quality of their songwriting but rather in order to maintain dramatic tension between characters: this still has to be entertaining TV. Nowhere was it more blatantly obvious than in shots of Granger’s own disbelief at having his song—which he had just described as unsuccessful—come in first at the end of an episode.

Artificially-imposed narrative aside, Platinum Hit is an interesting first glimpse into the world of beatmakers and topliners. The role of melodies, titles, song concepts, and chord changes is contextualized within the construction of a successful artist’s facade, giving some much-needed perspective on all that’s behind the front end of hit music.

The final episode of Season 1 airs this Friday August 5th.

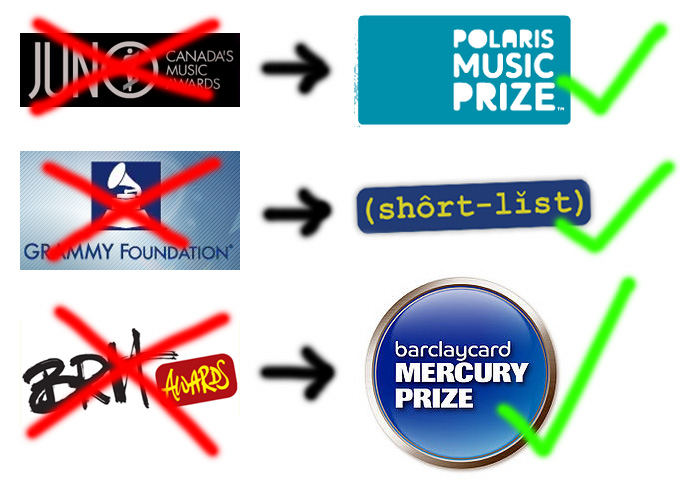

Pop Smarts: Robyn

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Labels, Production, Writing on November 4, 2010

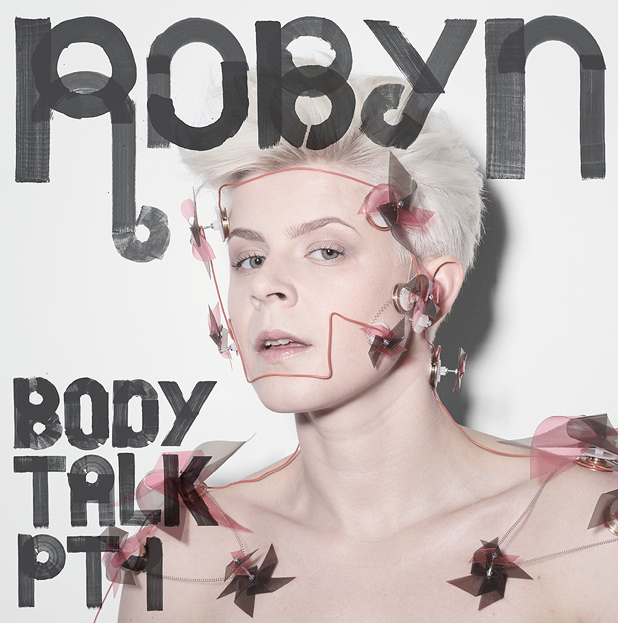

In 1997, RCA Sweden and legendary writer-producer Max Martin unleashed cute 18-year old popster Robyn on the world, sending flares up international charts with the R&B-tinged ‘(Do You Know) What It Takes’ and ‘Show Me Love’. The rest of the world was left to wonder once again how—from Abba to Roxette and The Cardigans—many a Swede has been able to tap in effortlessly to the North American pop sensibility. Further, she was a nordic girl with a measure of genuine soul in her voice. After a few more minor hits in Europe, Robyn disappeared from the world stage as quickly as she had arrived.

Fast forward a decade.

Word of mouth began rippling through the English-speaking world: undefeated by her major-label crash-and-burn, she’d quietly and intelligently risen from the flames. Taking the reigns both creatively and businesswise, she’d honed her songwriting craft with some hot producers and tested a new electro-pop direction locally with singles like ‘Dream On’. After necessary alterations, a deftly conceived full-length album—titled, simply, Robyn—followed on her newly christened Konichiwa Records. (The album also kicked off with the braggadocio rap ‘Konichiwa, Bitches’ — it’s Japanese slang for ‘Good Day’.)

A further revised version of the album arrived internationally and was supported with exhaustive touring. In concert she gives 110%, with heaps of cover songs along with her extensive canon of self-penned work. Her choice of covers shows a wide appreciation of other artists’ work: ‘Buffalo Stance’ by Neneh Cherry, ‘Try Sleeping With A Broken Heart’ by Alicia Keys and ‘Hyperballad’ by Bjork. Why all the YouTube links in this post? Because each one is worth it.

What’s special here is not that she’s come with great material, or that she put in the grunt work to rebuild the value of her brand from the ground up. It’s that she has the rare gift of self-awareness as an artist; the intelligence with which she’s packaged and marketed herself.

This year was the best example of it yet. After a couple years of radio silence, late 2009’s stunning collaboration with Röyksopp, ‘The Girl And The Robot’, primed us for a well conceived three-part ambush in 2010. Rather than releasing an album, she presented three shorter EPs. Distilled, the contents of Body Talk, Parts 1-3 would make a solid longplay album. But in an era when digitally downloaded music makes the number of songs on a release irrelevant, by conceiving a flexible new model like this she’s found a way to keep the excitement going all year long. Installments arrived in June and September. The final disc is slated for November 22.

Musically, the Robyn formula is smart. By giving us 1 part emotionally-level dance fun (‘Handle Me’, ‘Dancehall Queen’, ‘We Dance To The Beat’) and 1 part pseudo-gangsta attitude (‘Curriculum Vitae’, ‘Don’t Fucking Tell Me What To Do’, ‘Fembot’) upfront, we’re ready to go the distance with her as her heart bleeds through the remaining third of the material. And this is the material that really sticks: ‘With Every Heartbeat‘, ‘Be Mine‘, ‘Dancing On My Own’, ‘Hang With Me’, ‘Indestructible’.

Cleverly, the first two EPs also contained acoustic ‘preview’ versions of the lead-off single planned for the next EP, guaranteeing a boost of familiarity when the single versions of ‘Hang With Me’ and ‘Indestructible’ arrived with a Giorgio Moroder-esque thud.

What’s also striking is that Robyn, the artist and the businesslady, seems to have captured a demographic few else realized was there for the taking: the 30-something ex-raver that still craves rap and club music but wants something personal, melodic…clever.

The Creative-Commercial Cycle: How Pop Eats Itself

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Labels, Management, Production, Radio, Writing on August 19, 2010

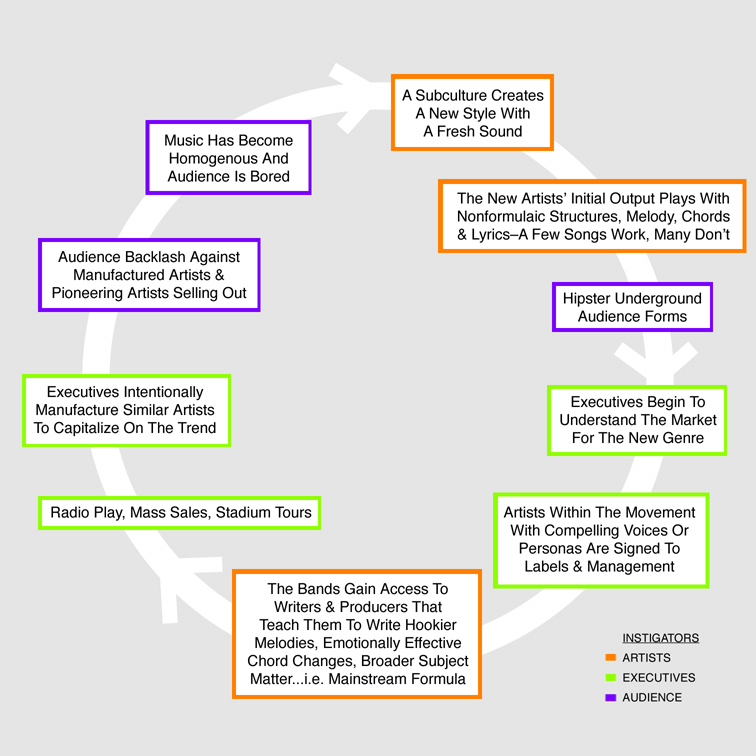

If it’s agreed that the following creative-commercial cycle occurs continuously in popular music…

…then there are a couple of things I find interesting. Namely, the process by which naturally compelling artists learn to create music with mass appeal, and the fact that this cycle seems to be speeding up as the executives get quicker at identifying and exploiting new trends.

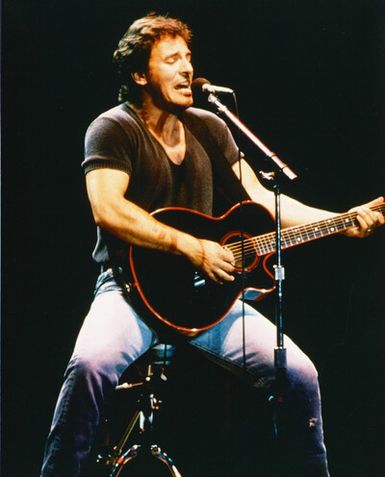

For an example of the cycle, we can look at U2’s output. In the early 80s they had underground ‘alternative rock’ cool factor. The songs on their first two albums Boy and October were somewhat freeform. Melodies were cockeyed and noncommittal, lyrics never too direct. Bono’s voice and Edge’s guitar sound, together, supplied compelling personality. Steve Lillywhite’s production captured the band’s raw electricity without stylizing it.

War and The Unforgettable Fire followed, with ‘Sunday Bloody Sunday,’ ‘New Year’s Day’ and ‘Pride (In The Name Of Love)’ showing the first signs of a desire to write for radio. However, an inspired change in personnel brought a new depth to the sound of that fourth album: ambient visionary Brian Eno and roots musician Daniel Lanois were brought in to produce.

Not surprisingly, the subsequent writing on The Joshua Tree was significantly distilled. The straight-ahead stock chord changes and emotive melody of ‘With Or Without You’ as well as the clear, sweeping subject matter of ‘I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For’ and ‘Where The Streets Have No Name’ brought a mainstream audience to them as if by magnetic pull. If Eno and Lanois hadn’t purposely educated the band about mainstream pop writing, some form of growth-through-osmosis had happened as they opened up their creative circle.

Here’s a wordy section from ‘Drowning Man’ on War, followed by the confidence of the continuously building ‘With Or Without You’.

Since the watershed success of that album and the Rattle & Hum stadium tour–amid their core audience’s protests that the band had sold out–U2 has ridden out the last 20 years in various states of expectation-busting experimentation (Zooropa, The Passengers’ Original Soundtracks project) and pop duty fulfillment (All That You Can’t Leave Behind).

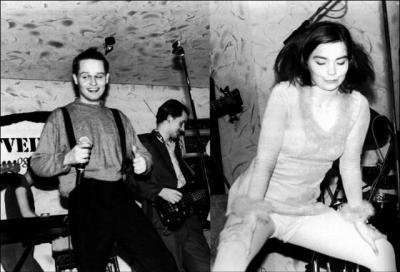

Bjork–who, incidentally, at first used her voice much like Bono had in the early 80s–first helmed Icelandic band Kukl, followed by The Sugarcubes. Her childlike voice and persona showed commercial promise amidst the disarray of the bands’ post-punk art-rock.

Teaming up with respected electronic producer Nellee Hooper, she emerged as a solo artist in 1993 with Debut, securing her place in pop history. The follow-up album was Post. ‘It’s Oh So Quiet,’ the big band single America loved to hate, was as straightforward as she would ever get before making her way back into ever-deeper experimental waters.

Compare the atonal rant from ‘Copy Thy Neighbour’ by Kukl with the soaring melody on the chorus of ‘Hyperballad’.

10,000 Maniacs is an interesting case that I made an effort to crack recently. I always had a like-hate relationship (as opposed to love-hate) with their In My Tribe, Blind Man’s Zoo and Our Time In Eden albums because I never quite understood how a band could sabotage moments of melodic virtuosity with such poorly considered arrangements. Or how such a compelling voice–meaning Natalie Merchant’s vocal instrument as well as the interesting angles she took on the songs’ subject matter–could be ruined by an equal helping of preachy condescension. As well, even after a string of five pop singles (‘Like The Weather,’ ‘What’s The Matter Here,’ ‘Trouble Me,’ ‘These Are Days’ and ‘Candy Everybody Wants,’) the band seemed to retain ‘alternative’ cred. Surely it couldn’t just have been based on their name.

A listen through their early recordings, reissued later on Hope Chest and The Wishing Chair, explained much. Like early U2 and Kukl, these songs are meandering stabs at writing, with hookless melodies, wordy, unclear lyrics and unremarkable chord changes. Also like Bono and Bjork, Merchant’s singular personality came through in her voice and the way she used it. 10,000 Maniacs guitarist Rob Buck, too, had an original style. Perhaps not as iconoclastic as Edge’s, but enough to show promise to a record company like Elektra. The band’s ‘alternative’ roots show in these recordings: in addition to the beginnings of their brand of quirky rock, we’re taken through painful world music experiments in Soca, Zouk and Dub Reggae.

‘Death Of Manolete’ from Hope Chest demonstrates the freedom of their wide-open creativity while the exquisite ‘Dust Bowl’ from Blind Man’s Zoo shows us the focus that took hold by the band’s second album with major label producer Peter Asher.

And so we have the artists, feeling around for something new to chew on, and the executives, racing to learn how to capitalize on a movement, a sound, an idea, a persona. They can’t exist without each other, so I don’t mean to imply that executives are the Cruella DeVilles of the world. But the crops need time to grow before the combine comes along to harvest. And in the age of the internet, traces of new artistic energy are identified and absorbed into the machine with breakneck acceleration.

One such ‘absorption cycle’ that makes me shudder is what occurred somewhere between 1995 and 2008, when Jill Sobule and Katy Perry each released a song called ‘I Kissed A Girl.’ Sobule’s song felt like the honest confession of a woman testing the fluidity of her sexuality. Perry’s felt like a market-researched ‘girls gone wild’ capitalization on straight mens’ fascination with girl-on-girl action. The sincere feminist perspective of artists like Sobule through the early 90s was officially absorbed into the machine when Simon Fuller auditioned British Barbie dolls for the Spice Girls. What was their mantra? ‘Girl Power’? Fast forward a decade, and it’s as though the feminist consciousness of the early 90s never existed. Lillith Fair sales are slipping this summer while the promo machine runs full-tilt for Katy Perry, who’s selling an updated Betty Page wet dream. Well, straight men still pull the budgetary levers at the major labels.

I was never fond of the smugly-named British band ‘Pop Will Eat Itself.’ As this creative-commercial cycle accelerates, however, I’m beginning to wonder if they were onto something. Adding momentum to this cycle is the fact that music went post-modern about 20 years ago. That is, sampling signified the gradual decline of truly new forms of pop music in favour of mixing original combinations of retro styles. If artists’ formulas weren’t made of old ingredients, it would be that much harder for executives to hack the recipe.

The ‘no rules’ artist to watch at this moment is Janelle Monae. She’s 24, she’s thoroughly disregarding anything that might be put on her as a female or a person of colour (in her own words: ‘I don’t have to do anything by default’), she’s got a big budget and she’s interesting. And–oh yes–she can sing. She can perform.

Andre 3000 and Big Boi of Outkast began working with her years back, and P. Diddy, of all people, has diverged from pop formula long enough to sign her and give her the kind of backing true artists only dream of in 2010.

Her trip is highly conceptual. Through a four-part suite, she’s reportedly telling the story of a robot named Cindi Mayweather who orchestrates an uprising in Metropolis. Her lyrics are so cryptic, however, that this storyline is barely apparent in the songs. At this early stage her output is coming across as a whole lot of disjointed concept, borrowed from many sources. If Fritz Lang doesn’t turn over in his grave at her shameless appropriation of his story, other visionaries like James Brown might. Virtually every song ends up a pastiche of the styles of several decades over the last century.

Melodically, the material is somewhat flat, the most memorable hooks lifted from elsewhere. Near the beginning of ‘Many Moons,’ a single from 2008’s Metropolis: The Chase Suite, she blatantly bites a riff from the Sesame Street pinball song we all know. After escaping the distraction of the very high budget of the ‘Many Moons’ video, it struck me that the most memorable moment of the song itself was that riff.

Selections from the new album, The ArchAndroid, include: ‘Cold War,’ its arresting single-shot video summoning the moment Sinead O’Connor shed a single tear for the camera in ‘Nothing Compares 2 U’; ‘Tightrope,’ with its main ‘on the scene’ hook lifted from ‘Sex Machine,’ (something she appeared to cop to as she donned a James Brown cape while performing it on David Letterman); ‘Sir Greendown,’ something like Shirley Bassey singing a version of ‘Moon River’; and ‘Make The Bus,’ like an outtake from David Bowie’s 70s trilogy produced by Brian Eno.

Another album track, ‘Locked Inside,’ feels good because it’s written over the chords of Stevie Wonder’s ‘Golden Lady’. It’s all crammed in there, cryptic and disorganized, from cabaret to hot jazz horns and 80s hip hop. And though it’s the work of an artist getting her bearings, both overdoing the concept and underdoing the original substance, she does appear to have the potential to change the game.

In order to keep that high budget record deal so she can mature creatively, it’s important that she have a bonafide hit sometime soon. And for that to happen the songs may have to fit into a framework that people understand a little more readily. There’s the catch-22: before the artist can ignore creative boundaries and lead the way, it seems she must first learn to simplify her writing. In days gone by labels could allow an artist several albums to reach a commercial stride. These days, it’s possible that other executives may be able to pinpoint what’s special about Monae early on and manufacture other acts that are capable of overtaking her. Hurry, Janelle, hurry and grow your garden!

People In Your Neighbourhood

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Labels, Management, Singing, Writing on July 15, 2009

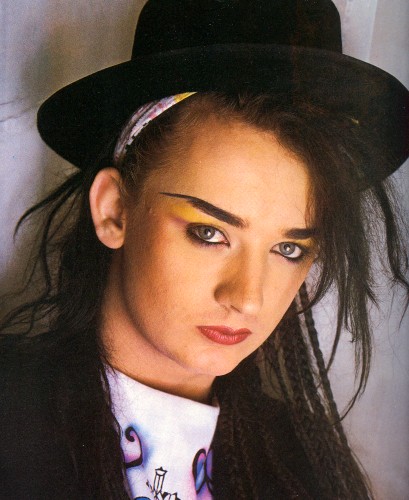

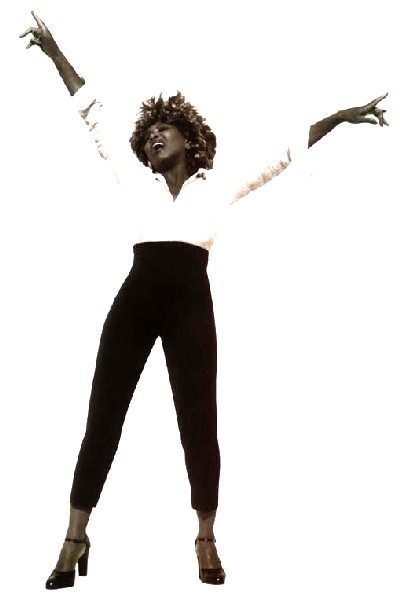

At the height of Culture Club’s success I remember people complaining that Boy George should have been able to make it solely on musical talent, without needing to resort to gimmickry…ie dressing in cosmopolitan drag. He was a talented writer and singer, but–consciously or unconsciously–he realized that audiences are not attracted to artists purely on the merit of their musical output.

We know this is true because there are endless examples of uniquely talented musicians that never garner a substantial following. That’s because what actually attracts us, as listeners, I believe, is an artist’s identity.

It’s true that this identity is built in part around the style and content of the songs, including the lyrics and the overall tone/sentiment. But for a star to be born, it’s critical that the music align properly with a host of other attributes, including the voice they were born with and the way they choose to use it; the physicality they were born with and how they choose to dress it up; how they move; and how they interview. The persona constructed with these tools needs to be instantly recognizable and compelling. (I won’t go so far as to say ‘appealing’, because there are plenty of celebrities that we love to hate.)

Speaking recently of the Supremes, Diana Ross wasn’t the lead singer of the group because she had the best voice in a technical sense. But her effervescent look and pastel-sounding voice combined to make her a compelling figure: she had instant identity.

Whether it’s the first few lines of a song, or a photo in a magazine spread, the audience needs to get a sense of the artist’s identity similar to the impressions we form of the people in our neighbourhoods we see around but haven’t had personal conversations with yet.

Here are some artists with identities so clear and compelling, whether we like them or not we all feel as though we know them from around.

All musicians are driven to make music. Those that are also driven to author every aspect of their public persona–from clothing to video treatments–end up having a lot less time to sleep but they have an edge over the rest, both in terms of career control and potential for success. That’s because most of us lack the ability to stand back and get a clear perspective on who we are, pinpoint what’s compelling about ourselves and amplify it.

Those who can’t must rely on industry executives’ abilities to look inside them and tailor the right persona…a rare feat in itself. If they get it wrong, the project will fail either because the identity won’t be compelling, or the artist won’t be able to carry an ill-fitting persona for very long before the audience sees through it.

To Sign Or Not To Sign

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Labels, Management, Publishing, Radio on June 11, 2009

In 2000 Courtney Love made a speech at a music conference. She got out her calculator and demonstrated what happens when a band signs a dream deal with a major label and has a hit album: the label makes an average of $6.6 million and the band makes an average of $0. The way things are structured in those deals, all of the costs of recording and promoting an album are passed back to the artist, and unless the band has multiple hit albums in a row they don’t actually make money.

This is not to say that the band isn’t living a suitably Hollywood lifestyle–touring and enjoying the trimmings of success–or that they might not benefit in the long run from having their identity erected to ‘household name’ status above the deafening din of all of the other aspiring musicians in the world. The major labels have built networks of promotional resources around themselves precisely for that purpose.

However, almost ten years after Love’s math class, the sea change in the music industry has lumbered forward. File sharing has won: physical product and the ‘brick-and-mortar’ stores that stock it are no longer necessary. All the filler labels used to cram onto CD-length albums is systematically ignored now that legal and illegal digital downloads are the norm. The majors have eaten up the rosters of even more independent boutique labels, destroying the influence of some of the innovative thinkers of those startups in an attempt to eliminate street-level competition. Sony and BMG merged, bringing the major label count down to four…that is, four clumsy multinational giants plagued with red tape and corporate approval hierarchies in a business that is utterly out of touch with ‘what the kids want’ because gut-level instincts have given way to copycat marketing models.

Essentially, it’s become common knowledge among insiders that for the foreseeable future, the major labels are going to be good for one type of music: music mass-marketed to 11-year old American or British girls. The artists doing that kind of music are often primarily concerned with fame, so they’re not thinking much about the money, assuming it will follow. They will rarely make a cut of the most potentially lucrative income source–writing royalties–because the labels will bring in professional writers who will come up with commercially viable material…or at least material that the radio stations will throw their support behind when they see writers with a track record of radio hits in the credits.

The labels all have sister companies in the music publishing world (Sony has Sony ATV Publishing; Warner has Warner-Chappell Publishing; EMI has EMI Music Publishing) that represent hit-making writers, and the cut those companies make gets routed back into the machine. It is true that often, however, the artist’s manager will insist that their non-writing artist come up with a line or two in a verse so that they’ll be cut in to the royalties at least in a minor way…and with their name in those credits, they’ll be perceived by fans as a singer-songwriter. (And this eventually leads to non-writing artists being offered lucrative publishing contracts, if their records are selling well.)

If you’re doing music aimed at anyone other than tweens, it’s probably a safer bet to stay indie, own everything and work hard to cultivate a solid grassroots fanbase. At this point in time, the majors are hemorrhaging money, so they expect artists with loftier musical ambitions to have done their own ‘artist development’…ie come up with their own image and styling; work out the details of their stage show; write some hit songs and grow an audience. So, ironically, if you do find yourself in the middle of a bidding war between the majors you may realize there’s not much more they can do for you. You might as well keep 100% of your profits rather than turn over 50-90% of your profits to somebody who didn’t show their support by investing in your potential earlier on.

There is no one ‘evil person’ at the helm of all of this financial deception. Artists are often focused on making their music and consider themselves not particularly business-minded, so they ignore the work they need to do to educate themselves.

Many execs at labels and publishing companies are failed artists, or people who dreamed of being artists but never believed in themselves enough to give it a real shot. They want to stay involved in the industry, for the love of music or the cool factor, but how many execs could possibly have the instincts of industry legends like Atlantic Records founder Ahmet Ertegun, a man whose understanding and raw passion for music led him to build a diverse stable of equally legendary artists?

These days there are so many jobs on the line in these multinational record companies, risk-taking of any kind has consequences…hence the constant references to existing successes: ‘make a track like Bleeding Love by Leona Lewis.’ And the writers and producers all scamper off to study how the reference song is constructed, coming back with paler and paler imitations; further and further from what a hit song is supposed to be: an epiphany.

It’s a simple fact of the economy that growing a band on a global scale over a series of albums is now financially impossible. So, as Howard Jones would say, no one is to blame. I suppose you could waste your time blaming the forward march of technology, specifically mp3 compression and high-speed internet, the way the advent of sampling was once demonized. But industry guru Bob Lefsetz, for example, trumpets on a daily basis in his blog that the majors are on their last legs because they constantly miss the boat by fighting technology rather than finding ways to capitalize on it. He also repeats relentlessly: be a good, original musician; write good, original songs; do it because you love it and not because you’re looking to get rich. In other words, Build It And They Will Come.

I think most musicians commit to their vocation at an early age with the erroneous belief that a good song by someone with a great voice becomes a hit because everybody in the industry goes out of their way to make it so in the name of sharing exceptional new music. Most music fans who are industry outsiders exist their whole lives believing that this is so. They may have heard that the entertainment industry is full of sharks, or that it’s a hustle, but people rarely hear concrete explanations of shady practices.

A few things to think about when considering signing with a label, publishing company or manager:

– Most radio stations are corporate entities now, often with multinational parent companies, and they have strict ‘formats’ detailing specific parameters (style, length, song structure) for what they play. The major labels have departments that feed the stations with material, and the stations trust the labels to bring content their listeners will be excited about. If you go the indie route, expect to pay an independent radio promoter several thousand dollars per month, per song, to try to get your material played on a specific format. The success rate for the investment is lower than if you are with a label. Material rarely gets in the door without a promoter. Whether radio is important anymore, with YouTube promoting most music, is another discussion entirely.

– If you do not live in the country where the head office of the label or publishing company you’re interested in is located, you will be trying to attract the attention of executives who have limited power over their artists’ destinies. In other words, if you sign with EMI in any country other than the UK or you sign with Universal, Warner or Sony in any country other than the US, your music will never be released in other countries unless the head offices there can be persuaded to back you as well. Writers signed to the offices of major publishing companies in countries other than the US or UK have their material pitched for use in movies, television and ads after domestic writers’ material is pitched as the head office stands to make less of a cut on foreign writers’ material.

– It’s critical to get the right fit: if you sign to the biggest label or publishing company because of their clout, and the individuals working at that office are not particularly excited about your music, you may find your project constantly blocked or shelved. Then it’s a waiting game to be released from your contract so your career can move forward. It’s also not unheard of for labels to sign artists with no intention of putting out their music…rather, the goal was to eliminate competition in the genre of one of the company’s existing artists.

– The same goes for managers. If you sign to the most powerful manager in your city–paying them 20% of your income for a period of years–make sure that they’re interested enough in your career that you are a priority for them. If that manager has another artist that blows up worldwide, you may find your needs ignored. It’s often better to be self-managed than managed by the wrong person.

– Because of their unique position negotiating contracts between parties in the industry, music lawyers know most of the players…be they labels, managers, publishers, producers, artists or writers. Often lawyers will help people network with each other, but watch out for biases and vested interests.

– Owning all of your publishing on a hit song can be very lucrative, however owning 100% of a song that isn’t being pushed to the right artists or advertisers is owning one hundred percent of nothing. The right publisher can help you make a living by pitching your material and setting up writing opportunities with artists. However if a television series is looking to use one of your songs, for example, they must clear its use with all parties who own a share. The more parties involved and the bigger the publishers, the more red tape…making it too much of a hassle for some agencies to bother with.

Cashflow In The Music Industry

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Labels, Management, Publishing on May 18, 2009

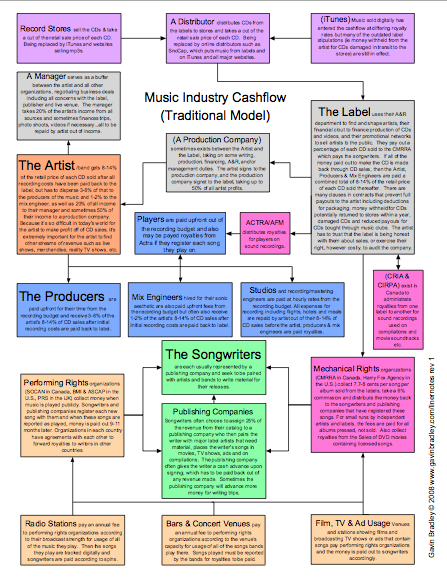

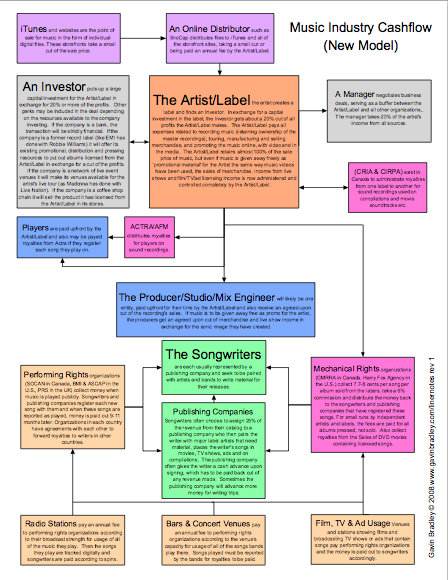

The industry is huge. There are all sorts of organizations that funnel royalties down to artists, writers and producers. I couldn’t keep it all straight in my head, so I finally made a couple of flowcharts.

One flowchart illustrates the traditional flow of cash, and the other gives some shape to the new model that we see forming, wherein the major labels are replaced by investors (of any kind) and each artist releases their material digitally on their own indie label. Right-click or Control-click (Mac) to download a legible PDF.

I recommend reading these from the top left corner. That way, your eye will guide you through the information in a way that makes sense. Colour coding is by ‘branch’ of the industry (income from sales of recordings, income from performance of songs etc.).

This is a work in progress. If there are errors or omissions, by all means let me know. For example, booking agents will be added in the next iteration.