Archive for category Engineering

Pressed Up Against The Glass: Visualizing And Discussing Sound

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Engineering, Mixing, Production on August 11, 2010

In 1966, during the recording of ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ for the Beatles’ Revolver album, John Lennon came up with a request phrased in the language of an artist: ‘I want my voice to sound as though I’m a Lama singing from a hilltop in Tibet’.

Producer George Martin had to interpret this request and come up with a concrete plan of action, which he then had to describe in technical terms to the recording engineer, Geoff Emerick, and the other assistants working under him.

Martin’s plan, documented in BBC’s interviews with George Martin on The Record Producers, was to play back the vocal track through a spinning Leslie speaker inside a Hammond organ and record that. I don’t know if the resulting warbly sound was exactly what Lennon had heard in his mind, but he was delighted with the freshness of the effect.

One of the greatest challenges producers face is coming up with the right language in discussions with artists and engineers. We’re all supposed to be sculpting the same thing. Mixing, for example, involves deciding on the placement of each instrument in a song – from its relative volume and clarity to its spatial positioning in the stereo field. Since we all interpret and describe sound differently, how do we take the seed of an idea born in one person’s esoteric imaginings and explain it clearly to a team?

The right metaphor helps.

A friend with musical leanings (and great skills in metaphor) once told me he likes to feel that he can walk into a recording and move around, visiting each instrument at will. He earmarked Steely Dan’s 1977 offering Aja as a good example of a sonically spacious album.

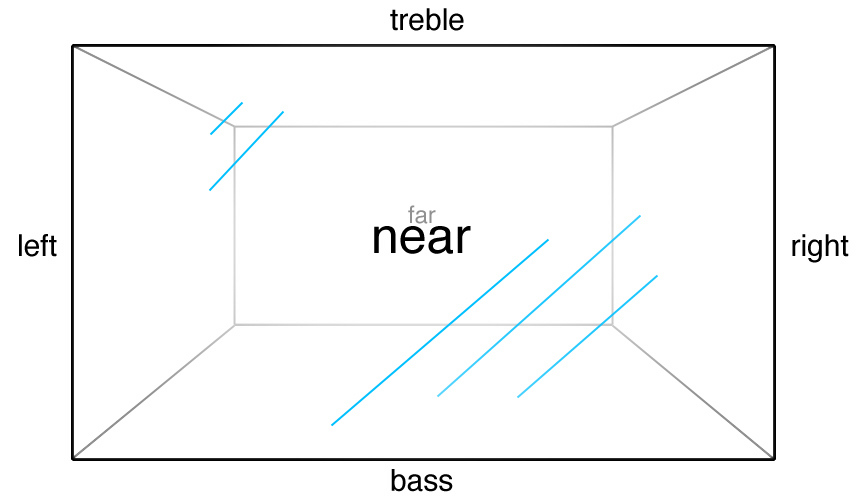

This idea of being able to ‘walk into’ a mix resonated with me, because I’ve always had a similar visualization of sound: I imagine the song is contained in a big glass box immediately in front of me. Sometimes I describe this model to the people I’m working with so we have a language for discussing our mix decisions.

In this box, a sound can be anywhere, left to right, in the stereo spectrum. It can be low or high, like the bass of a kick drum or the treble of a cymbal. It can be far away because it’s quiet and soaked in reverb (that residual echo of a bathroom or church), or it can be near because it’s loud and dry (just the direct sound with no reverb).

Trends in mix aesthetics come and go, and most of them are set in motion by an advance in technology. In the 60s drums were fed through analog compressors that tended to add a pleasing distortion, and big boxy reverbs were thrown on vocals using a huge room called an echo chamber. In the 70s 24-track recording became a reality and elements could be separated and controlled, making lush stereo arrangements possible. Digital reverb boxes came of age in the 80s, and reverb was applied liberally to snare drums and vocals.

Today the trend is for both of those elements to be almost completely dry. And recordings are significantly louder these days because with new digital compression plug-ins we can make each element much louder than we ever could in analog.

However when this is the case, as a listener I get the sense that the sound is aggressively being pushed out toward me–and pressed up against the glass–rather than inviting me in to explore. In fact I don’t like to be aware that there is a piece of glass between me and the music, but the more compression is used on the sounds in a mix to unnaturally increase their volume, the more obvious it becomes that the sound is hitting a wall, a limit. (Compression is explained beautifully in this two-minute video on the loudness war.)

This loudness war created a connundrum for radio stations that play both old and new music. Because their broadcast machines are calibrated for the loudness of newer material, older music sounded weak in caparison. That is why, a few years back, many major labels began remastering older music at higher levels in an effort to keep their catalogs in rotation–and to sell the same albums all over again to hardcore fans. Even if this meant the music sounded one-dimensional.

While striving to satisfy radio stations’ technical expectations, I look for ways to limit my participation in this ‘loudness war’ because aggressively mixed music tends to induce listener fatigue quickly. I want people to be able to put the records I produce on repeat! I listen to a lot of indie rock these days because those producers seem to have learned the subtleties of the new technology and found ways to make things impactful without flattening them against the glass in an obvious way.

My hope is that an upcoming technological breakthrough will steer us back toward utilizing the sonic depth we once valued. Most of the music I go back to exists casually in its space, enticing the listener in rather than forcing itself on them.

For Those About To Make An mp3…

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Engineering, Mixing, Production on June 22, 2009

…these guidelines will ensure that you don’t populate the web with awful sounding files.

- Don’t use ‘Joint Stereo’. This saves marginally on file space by allowing the left and right channels to share information as necessary, which results in warbling treble.

- Don’t use ‘Variable Bit Rate (VBR)’. This allows the file quality to lower when there’s less complexity in the music, and again you can hear the treble change as the file quality shifts fluidly like this. Always use Constant Bit Rate (CBR).

- The Sample Rate needs to be 44.1, like a CD. Lower it and lose quality fast.

- The only thing you should play with if you want to create smaller files is the Bit Rate, and don’t go below 128. 320 is very close to CD quality, and since most of us have high speed access now we should always be using it.

- Do not make an mp3 of an mp3, or an mp3 of a CD that was burned from mp3s. This makes worse and worse sounding files (see below for why).

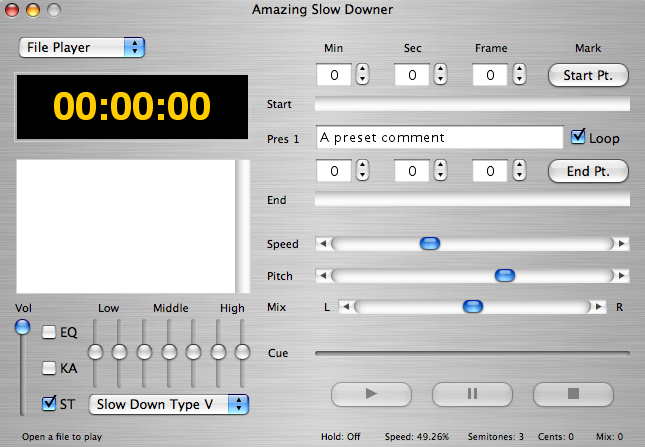

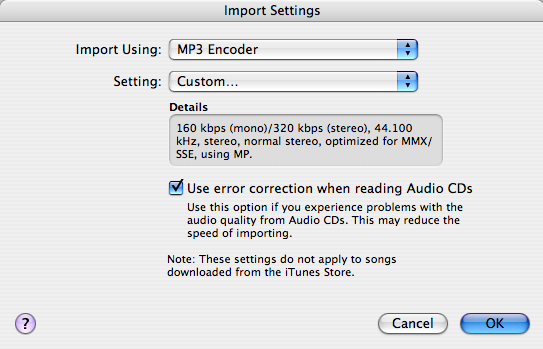

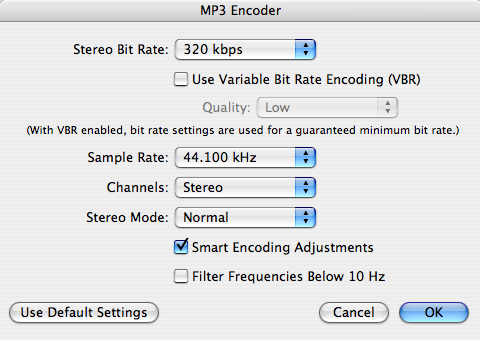

These guidelines go for whatever program you use for your mp3s. But to set this up in iTunes, open Preferences/Settings and click on the ‘Import Settings’ button. Where it says ‘Import Using:’ select the ‘MP3 Encoder’. Beside ‘Setting’ select ‘Custom…’

Then set things up this way:

In iTunes you do not want to check ‘Filter Frequencies Below 10 Hz’ because although we can’t hear bass that low, its absence does affect the impact of the sound we do hear. Check ‘Smart Encoding Adjustments’ though. Might as well be smart.

On another note…media files come in two types: ‘lossless’ (large files that capture all of the information (used for large-format print applications, store-bought CDs and DVDs) and ‘lossy’ (smaller files that approximate the sound or image, but are easier to share on the net).

So if you’re a graphic designer and you need high quality image files to print posters from, you use TIFF or EPS files…but if you’re designing for the web you use jpg or gif files. They’re not as visually clear, but on a small web page they look fine. What you don’t want to do is make a jpg of a jpg because the image will gradually degrade.

In audio, if you want to retain all of the information perfectly you use WAV, AIF or SD2 files (the highest quality file you can get from a standard CD is a 44.1 kHz stereo WAV/AIF file). But ever since file sharing began on the net, we’ve relied increasingly upon mp3, and mp4/AAC files.

If you make an mp3 from a CD or WAV file with the settings described above, you’re getting something that is virtually indistinguishable from the original CD. But if you open that mp3 file to make changes to it (like edit the beginning and end of it) and then you save it again, you’re making an mp3 of an mp3…and that’s akin to repeatedly making a jpg of a jpg, losing information each time. Here’s what you get if you keep making lossy files of lossy files:

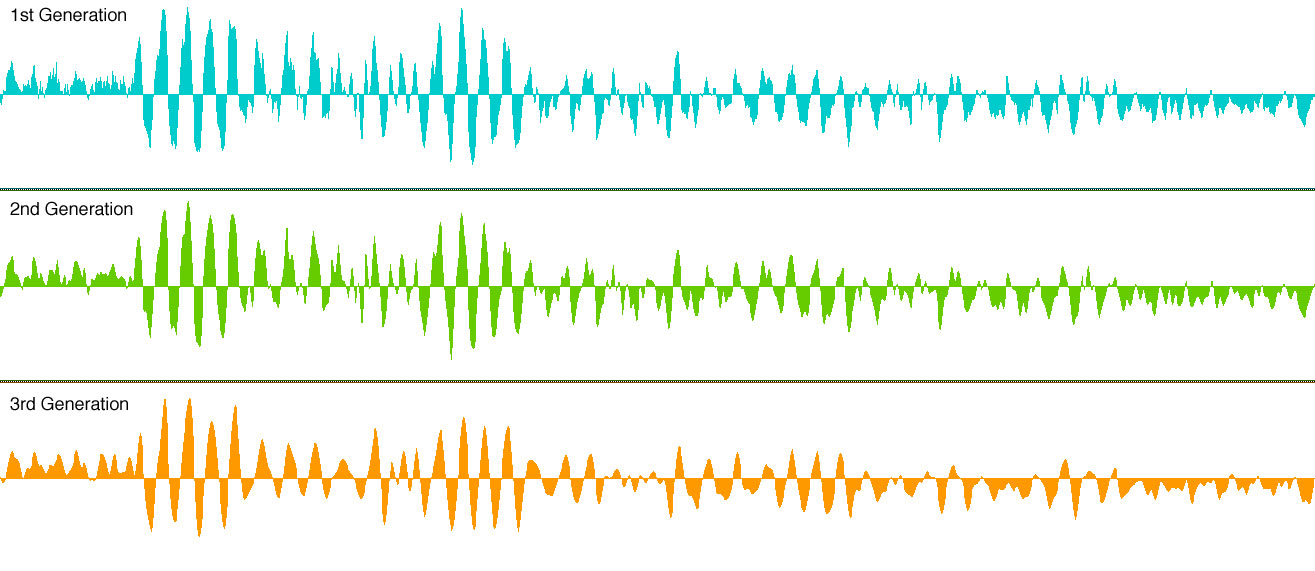

Below is what the sound wave looks like for the three passages you just heard…details in the wave get lost with each generation:

It’s especially important to be vigilant about this issue if you’re a producer who’s sampling off of mp3s to make your beats. Realize that when you’re done mixing your CD-quality WAV file, the first thing that’s going to happen is someone is going to make an mp3 of it. And then some of the elements in your track are going to lose impact because the source files were already mp3s.